Hannah Ridge examines the effect of constituency election victories and defeats on citizens’ democratic opinions in three majoritarian democracies: Australia, Canada, and Great Britain. She finds that winning in the constituency offsets the negative effect of electoral defeat at the national level; among national winners, however, the district result has limited impact on democratic attitudes. Constituency-level victories are less effective at mitigating the effect of national defeat on more diffuse democracy support.

Hannah Ridge examines the effect of constituency election victories and defeats on citizens’ democratic opinions in three majoritarian democracies: Australia, Canada, and Great Britain. She finds that winning in the constituency offsets the negative effect of electoral defeat at the national level; among national winners, however, the district result has limited impact on democratic attitudes. Constituency-level victories are less effective at mitigating the effect of national defeat on more diffuse democracy support.

In order for democracy to thrive, citizens must believe in it. They have to think that democracy is a good form of government, even if they do not consider it the best or only acceptable option. They also have to be pleased with the way democracy is functioning in their country. They have to believe that participating in their democracy matters and that the outcomes of their elections matter. Dissatisfied citizens are less invested in keeping their democracy instead of replacing it with a different form of government, and they are less likely to believe that democracy is the best system of government.

Researchers have identified several factors that drive citizens’ satisfaction with their democracies. Strong economies and social welfare, responsive governance, institutional quality, party diversity, and partisanship all matter. The most robust finding, however, is the win-loss satisfaction gap. Individuals who support the party that won an election are more likely to be satisfied than people who supported losing parties.

The extant literature has largely focused on the effect of winning or losing the top job. Control of the prime minister’s office and the associated superior influence over the policy agenda give good reason for such a gap. These voters have more reason to think their preferred policies will be enacted, and to believe the government cares about their interests. Furthermore, people like winning at things. The positive psychological and emotional effects of victory can translate into satisfaction with the rules and tools of the game that just delivered a pleasing result.

The parliamentary system, which the UK employs, however, can mean that very few voters actually vote for the prime minister. The Westminster system’s nested structure of elections introduces a quirk into the translation of winning into satisfaction with democracy. In this system, voters could sweep both levels, winning both their constituency and the prime ministership. The favoured party could win the premiership while losing their home constituency. The party could lose the premiership but win the parliamentary seat, or they could lose both races.

In a recent article, I examine the impact of these multiple simultaneous elections on citizens’ attitudes toward Westminster-style democracy. When do voters feel like they won an election? Research from Canada shows that voters who won doubly ‘almost unanimously think their party won the election’ and voters whose party took the premiership but whose party lost in their district ‘also overwhelmingly believe that their party won’. In these studies, citizens who won their home district but lost the top job are substantially less likely to think their party won the election than those who won the premiership; however, they are still more likely to identify a victory than those who doubly lost. This pattern suggests that the within-district results can soften the blow from a national defeat, while a district loss does not substantially take away from a national victory.

Using post-election surveys from recent elections in Australia (2013), Canada (2011), and Great Britain (2015), I find that citizens’ attitudes towards their democracy follows the same win-loss-perception pattern. National losers are less likely to be satisfied with the functioning of their democracy, they are less likely to believe that it matters for whom people cast their ballots, and they are less likely to indicate that it matters who is in power.

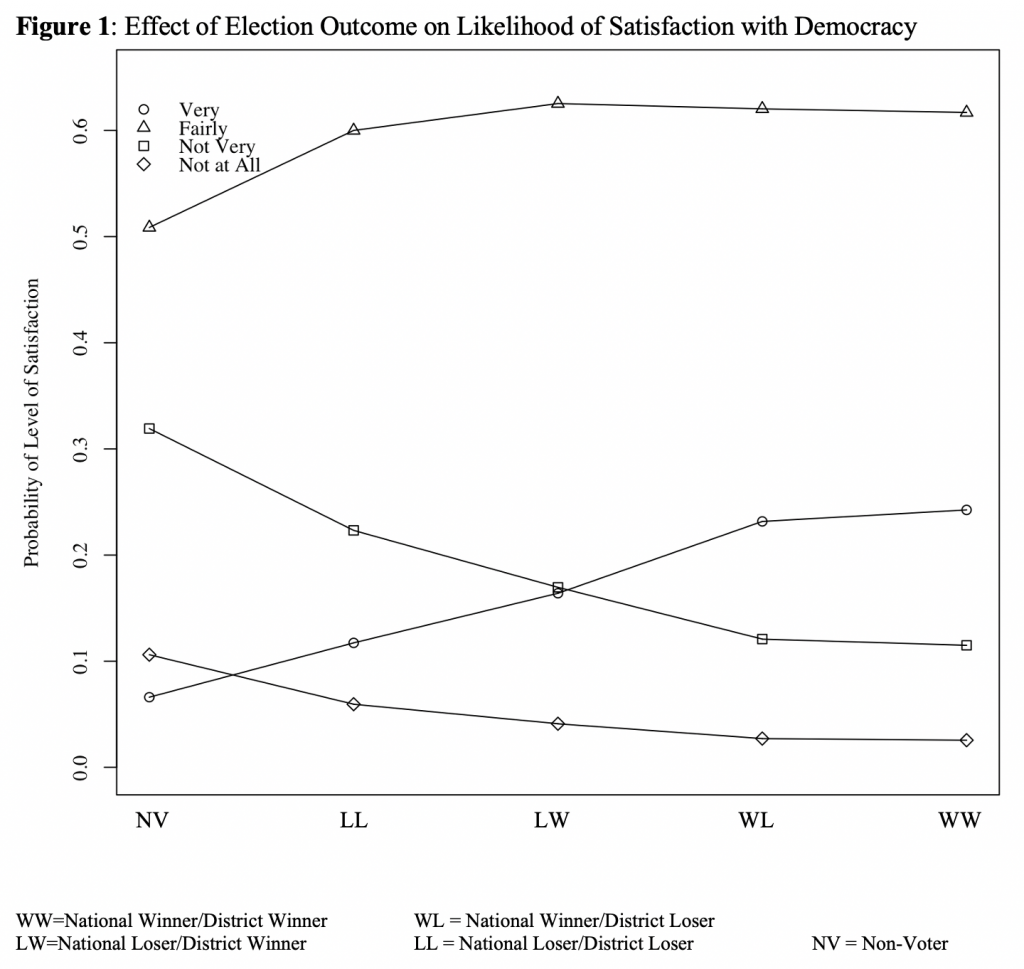

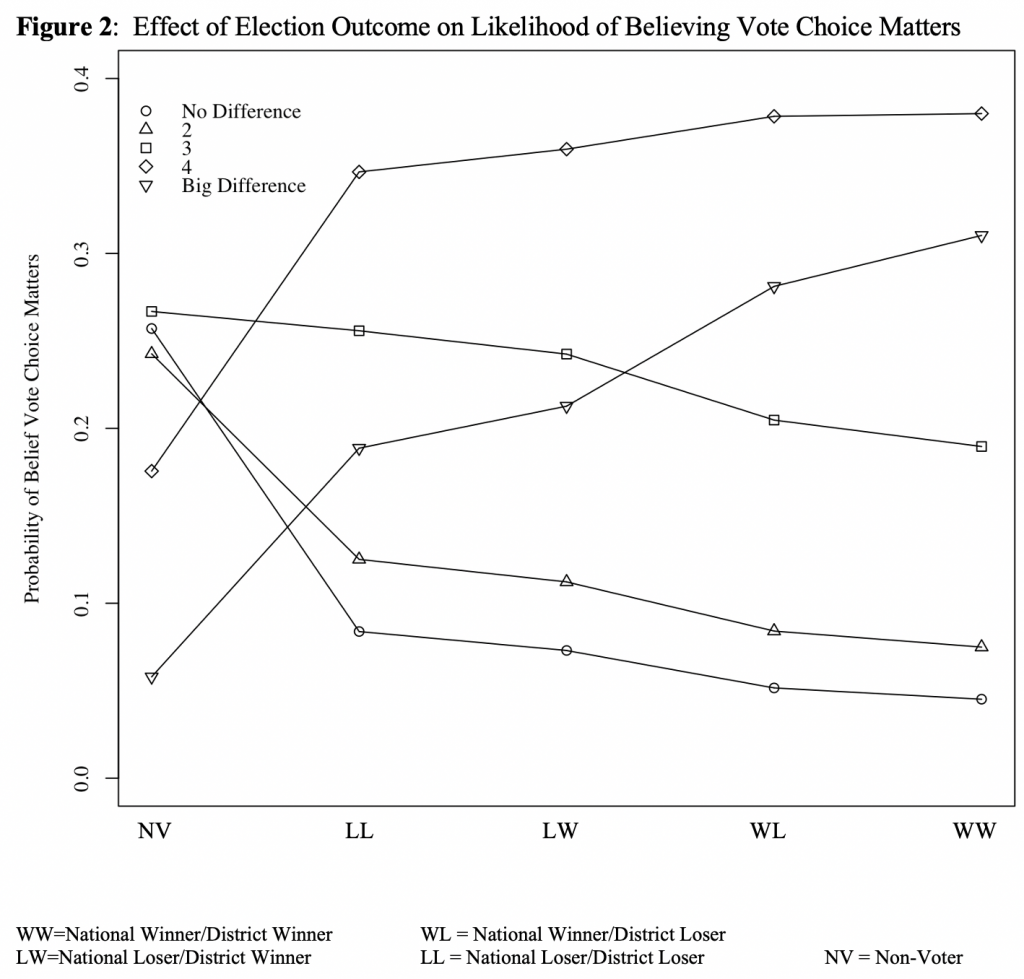

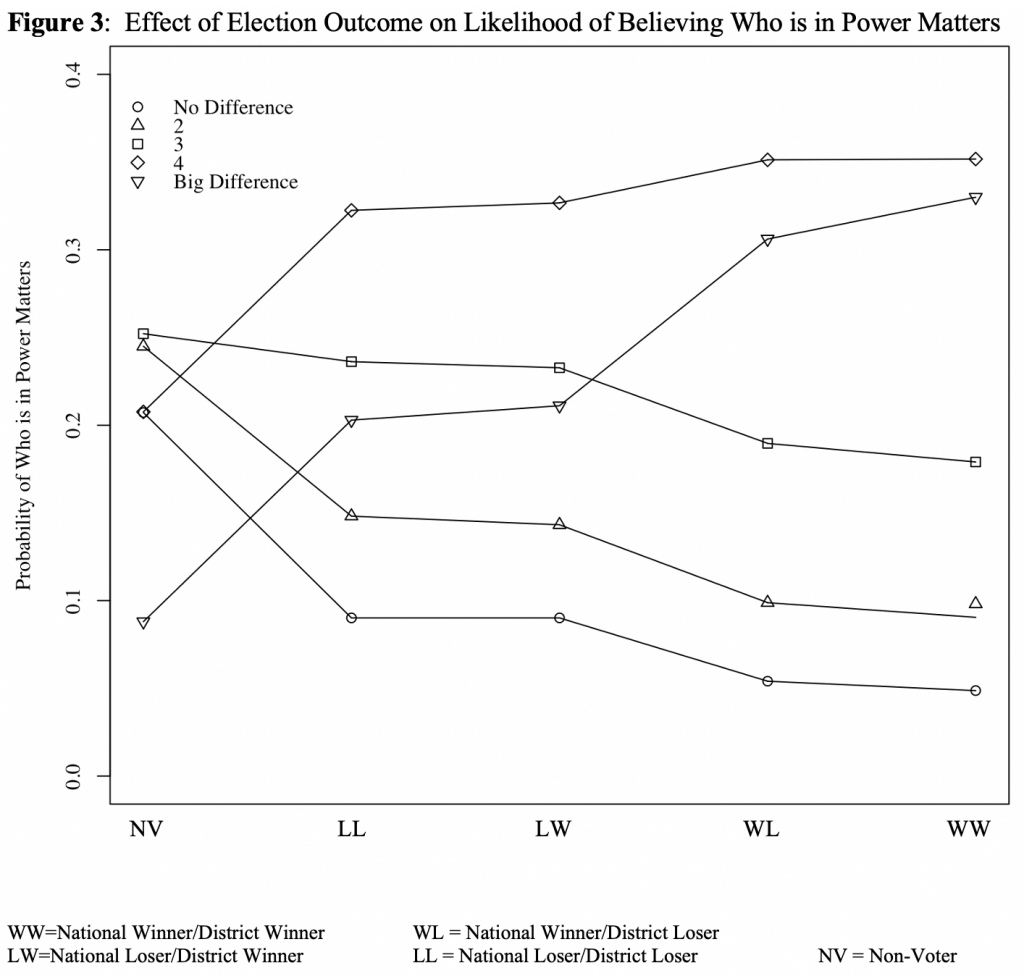

Among national-election winners, the district result does not substantially change citizens attitudes toward democracy. Winning the premiership makes them feel like winners either way, and they get the victory boost to their satisfaction. They also are more likely to report that it matters for whom they vote and who holds power. Among those national losers, on the other hand, the constituency outcome matters. Voters who won in their district are more likely to be satisfied with their democracy. The relationship between the district outcome and other democratic attitudes, while still positive, is weaker. They are more likely to believe that voting and outcomes matter, but the effect does not reach traditional levels of significance. The effect of victory on each of these opinions – estimated for a hypothetical voter – is shown in Figures 1-3.

Zooming in on Great Britain’s 2015 election results reveals a particular deviation from this general pattern. The pre-election polling showed a tight race, and voters who were not optimistic about their chances in the election were less responsive to the loss effect of electoral defeat. In the 2015 election, Conservative voters who lost in their constituencies were not more satisfied with British democracy than voters who lost in both elections. Although the Conservative Party picked up votes in the aggregate, some seats were lost, which could have caused hard feelings in those districts. On the other hand, voters who favoured other parties and won their constituencies were not significantly less satisfied than Conservatives who won both the top job and their constituencies. These national-loser-district-winners are largely Labour Party and Scottish National Party voters. This pattern could be attributed to SNP’s well-above-normal success in that election, taking near all the Scottish seats. As these voters likely never anticipated taking Downing Street, losing the premiership did not represent the same blow to them. For the SNP partisans, however, the Scottish district victories demonstrated clout and strong regional identity shortly after the unsuccessful independence referendum. Thus, their experience of national defeat is distinct from the generalised pattern.

Scholars link citizens satisfaction with their democracy and their commitment to democratic values to democratic durability. Electoral victory supports citizens’ belief in their democratic institutions, including system satisfaction and the importance of electoral participation and outcomes. As studies of trust in government have shown, ‘one way for losers to have few incentives to bring about system change is for them to have opportunities to become winners as well and thus to be part of the decision-making process’. Through these nested elections, which increase the number of voters who view themselves as having won an election, the Westminster system develops a pro-perpetuation structure. Winners of all stripes are more likely to keep British democracy strong.

____________________

Note: the above draws on the author’s published work in the Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties.

Hannah Ridge is a Postdoctoral Scholar in Human Rights at the University of Chicago. She earned a PhD in Political Science at Duke University.

Hannah Ridge is a Postdoctoral Scholar in Human Rights at the University of Chicago. She earned a PhD in Political Science at Duke University.

Photo by Oleg Laptev on Unsplash.