There are widespread claims that Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership of the Labour Party has entailed a shift to a more ‘radical’ and ‘left-wing’ form of politics. Yet, many of these claims are untested or lack clear empirical evidence. Rob Manwaring contextualises Labour’s policy agenda by focussing on the 2017 Labour Manifesto. He explains how the wider claims about Corbyn’s radicalism tend to mask some long-standing continuity in the Labour tradition, and simplify a more complex policy agenda.

There are widespread claims that Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership of the Labour Party has entailed a shift to a more ‘radical’ and ‘left-wing’ form of politics. Yet, many of these claims are untested or lack clear empirical evidence. Rob Manwaring contextualises Labour’s policy agenda by focussing on the 2017 Labour Manifesto. He explains how the wider claims about Corbyn’s radicalism tend to mask some long-standing continuity in the Labour tradition, and simplify a more complex policy agenda.

British politics is, somewhat inevitably, dominated by the politics of Brexit. The 2016 referendum result has triggered a significant realignment of British politics and the party system. Whilst we should be circumspect about reading too much into the longer-term meaning of the European elections, recent polling suggests a significant shift against the two key major parties. One key issue is that the sheer dominance of the Brexit means that attention shifts away from other significant changes (and also continuities). In terms of the Labour party under Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership, much of the current media scrutiny is on its position on leaving the European Union. Yet, this narrow focus, whilst clearly important, means that we have not fully understood how Labour has been changing under Corbyn.

In recent research, my colleague Evan Smith and I, examine Labour’s policy agenda under Corbyn. To do this, we focussed on Labour’s most recent election manifesto, ‘For the Many, Not the Few’, which outlined Labour’s policy agenda at the 2017 General Election. Using both quantitative and qualitative analysis, we wanted to put Corbyn’s agenda in context, and also better understand how Labour has changed and, crucially, what has remained the same.

To do this, we compared ‘For the Many’ with every Labour manifesto since 1945 (20 manifestos in total), using the Manifesto Research of Political Representation (MARPOR) database. The MARPOR database is the longest running dataset in political science, and rests on the salience view of voting, in that parties will give salience and preference to different policy issues at each election to win votes. The MARPOR data enables a comparative view to see how a party changes its policy agenda. For example, it is relatively straightforward to see how much space in the manifestos is given to an issue, such as support for nationalisation. We can then note how, over time, support for this issue can wax and wane. We then supplemented the quantitative comparison by examining it in more detail with four key ‘signature’ Labour manifestos. So, we give a qualitative comparison of how the 2017 manifesto compared against Ed Miliband’s 2015 manifesto, New Labour’s first (1997), the ‘longest political suicide note’ manifesto of 1983, and also the first of the 1974 manifestos.

Before giving a snapshot of some of our findings, we note two key issues in the understanding, and indeed, misunderstanding of Corbyn Labour’s policy. First, we looked at some of the press coverage of ‘For the Many’. We found that the press coverage of the manifesto in May and June was dominated by the language socialism. In nearly 4,000 articles in the mainstream newspapers we found the manifesto linked to terms such as ‘socialist’, ‘radical’ and ‘hard-left’. But, was it? Second, we reviewed much of the recent scholarship on Corbyn. There are a number of important contributions to understanding the rise of Corbyn, and a number of articles and essays seeking to understand his agenda. Yet we find a significant gap in the scholarly knowledge in understanding what Corbyn Labour is setting out to achieve. In our view, the press either mis-understand or wrongly frame Corbyn’s agenda, or in the academic literature we lack a detailed account of his policy agenda. So, what did we find?

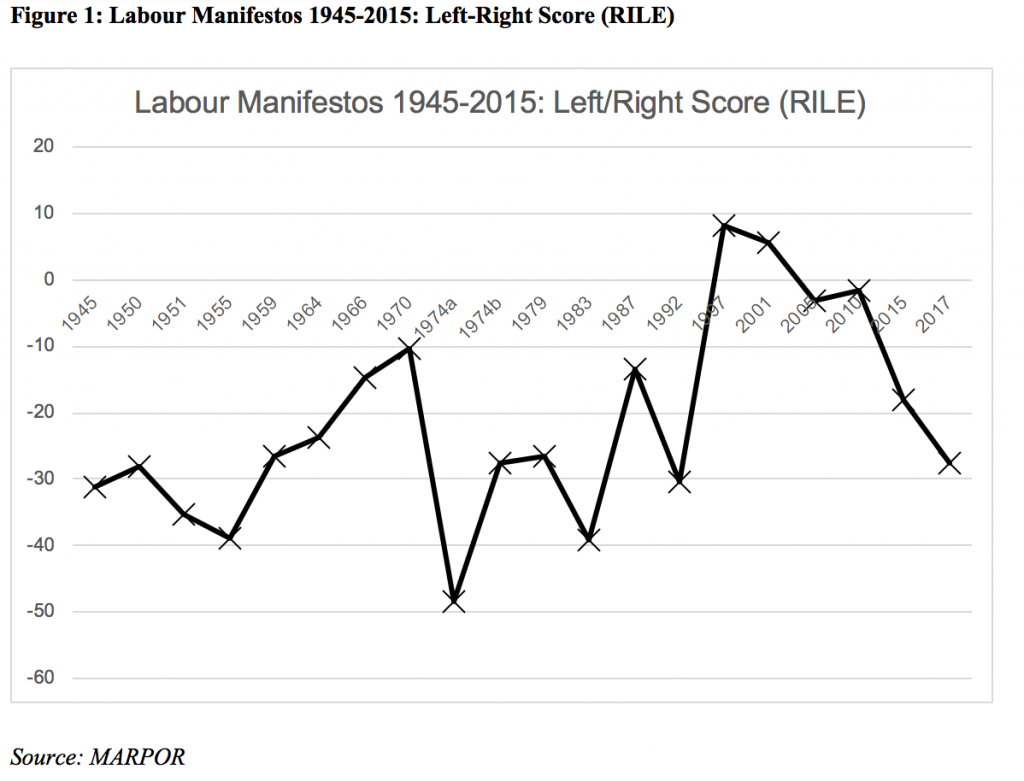

In sum, we find both continuity in Corbyn’s agenda with previous Labour manifestos, but also some changes. We also find some clear links with Labour’s policy agenda with the ‘New Labour’ manifestos. In Figure 1, we compared Labour’s score on the MARPOR left/right scale. Basically, the more ‘negative’ the overall coding score the more ‘left-wing’ the manifesto is. Whilst this is something of a crude measure, it does give a useful overview of the manifestos. Clearly, on this measure Labour’s 2017 manifesto is one of the most left-wing of the recent manifestos, and relatively speaking one of the most left overall (7 our of 19 are more ‘left’ than Corbyn’s). Yet, it is not as left-wing as the 1992 manifesto, nor is is it as ‘left’ at the infamous 1983 manifesto. We can also note that all the key new labour manifestos were the most right-wing in Labour’s recent history.

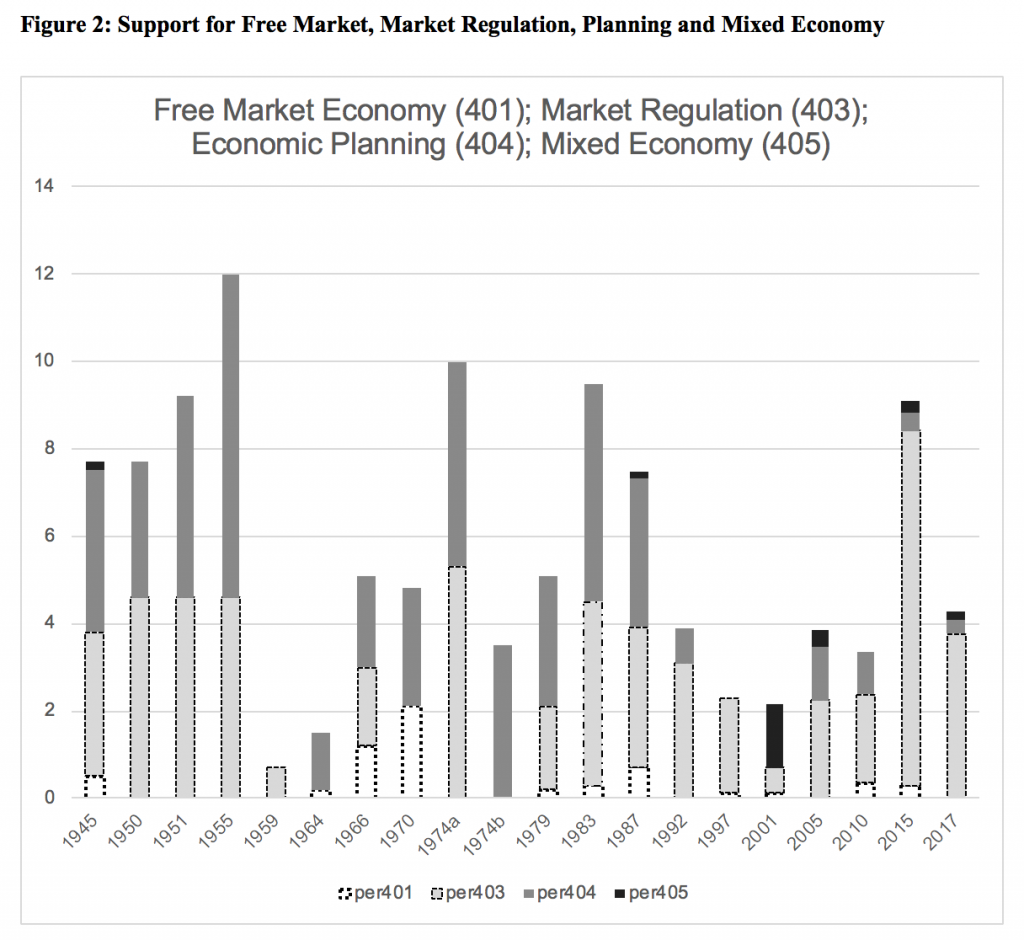

Yet, the left/right scale only gives a rather crude snapshot of the party’s agenda. We then drilled down into specific policy areas and issues to get a better sense of change and continuity in Labour’s policies. On economic issues, we see a more nuanced and complex picture. In Figure 2, we compared Labour’s salience of specific economic policy issues, its support for the free market, its support for market regulation, its preference for planning, and also the support for the mixed economy. We find no mention/support for the free market in ‘For the Many’.

For a social democratic/Labour party this is unsurprising, but it is worth noting that that whilst a mention of this in New Labour’s 1997 and 2001 manifestos this was very small, and indeed no mentions in 2005 New Labour manifesto. Whilst on these measures, Labour’s economic agenda is dominated by a strong focus on market regulation, we can note that this was a far more significant feature of Ed Miliband’s policy agenda. What is clear is that over time, Labour has moved away from a focus on using the instruments of economic planning to shape its agenda, and somewhat ironically we see slightly greater coverage of this issue in the latter New Labour manifestos. Corbyn’s apparent radicalism in this sense did not hark back to the 1970-1980 manifestos.

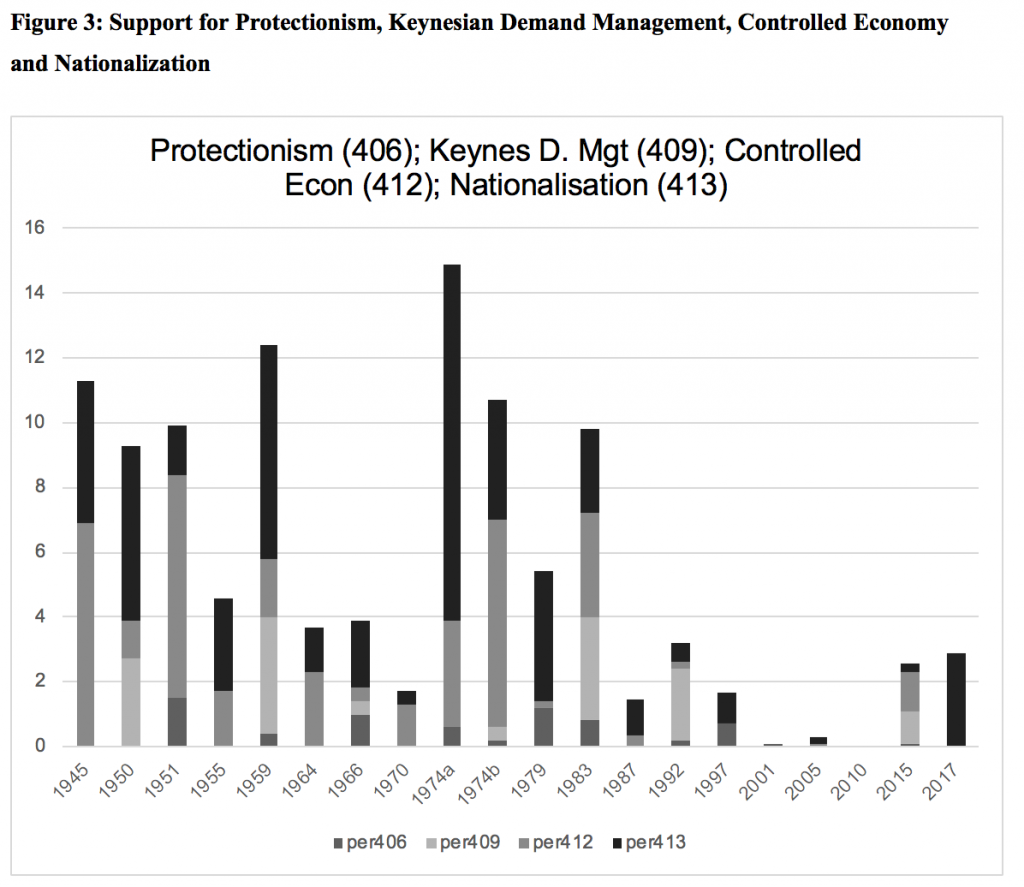

On a set of different economic measures, we do get a much stronger sense of what was different about Corbyn’s economic agenda. Figure 3 outlines four other indices (support for protectionist policies, support for Keynesian demand management, preference for a greater control of the economy, and support for nationalisation). Here, the great difference in Corbyn’s agenda is apparent, and what in our view fuelled the media framing of Corbyn’s agenda as ‘socialist’ – the focus on nationalisation. This by far, dominated ‘For the Many’, and the nearest comparison for similar levels of coverage was the 1983 manifesto. Nationalisation as a policy issue is almost non existent in Labour’s manifestos from 2001-2015. Yet, whilst on this issue Corbyn’s agenda does have more in common with the mid-late 70s and early 1980s Labour, it is striking how on Corbyn’s Labour gives little to no salience of a more Keynesian approach.

In the rest of the article, we examine and compare Corbyn’s agenda across a wider range of policy issues, including foreign policy, welfare, and support for specific population groups. Again, we find a complex story, and one that is under-appreciated. To a large extent, and in common with some commentators, in more recent times the policy renewal under Ed Miliband has been far more dramatic than Jeremy Corbyn’s. With some policy exceptions, Corbyn’s social democracy has a good deal in common with its historical forbears, and more in common with New Labour, than is sometimes supposed.

__________________

Note: the above draws on the author’s published work (with Evan Smith) in British Politics.

Rob Manwaring is Senior Lecturer in the College of Business, Law and Government at Flinders University.

Rob Manwaring is Senior Lecturer in the College of Business, Law and Government at Flinders University.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit:Jenny Goodfellow, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Thanks for the interesting article. That confirms my general impression. For example, the big spending pledges in the 2017 that I recall from the 2017 manifesto, apart from nationalisation, were a. the abolition of tuition fees; b. the triple-lock on pensions. These are not aimed at the poorest in society at all (who probably don’t go to university and may well have an highly patchy record of NI contributions) but at the middle classes. One imagines that a socialist government would sock the rich and spend the money on the poorest, but that wasn’t Labour’s policy.