Kemar Whyte discusses UK monetary policy and explains why the government does have room to act now and announce further support for vulnerable households rather than leaving them to face uncertainty until budget day in November.

Kemar Whyte discusses UK monetary policy and explains why the government does have room to act now and announce further support for vulnerable households rather than leaving them to face uncertainty until budget day in November.

Inflation in the year to July was 10.1 per cent, the highest it has been since February 1982. Real regular pay fell by a record 3 per cent in the year to 2022 Q2. And, at its meeting ending on 3 August, the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee voted by a majority of 8 to 1 to increase their Policy Rate to 1.75 per cent, the highest it’s been since January 2009.

The rise in borrowing costs would not have come as a surprise to most, but the gloomy economic outlook that accompanied the announcement probably did. NIESR’s economic outlook is not too dissimilar to that of the Bank’s. On 3 August, a day before the Bank published its forecast, NIESR published its own outlook for the UK economy noting that it is likely to enter recession in the third quarter of 2022 and remain there through to the first quarter of 2023. The Bank, in contrast, expected five consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth starting in the fourth quarter of this year.

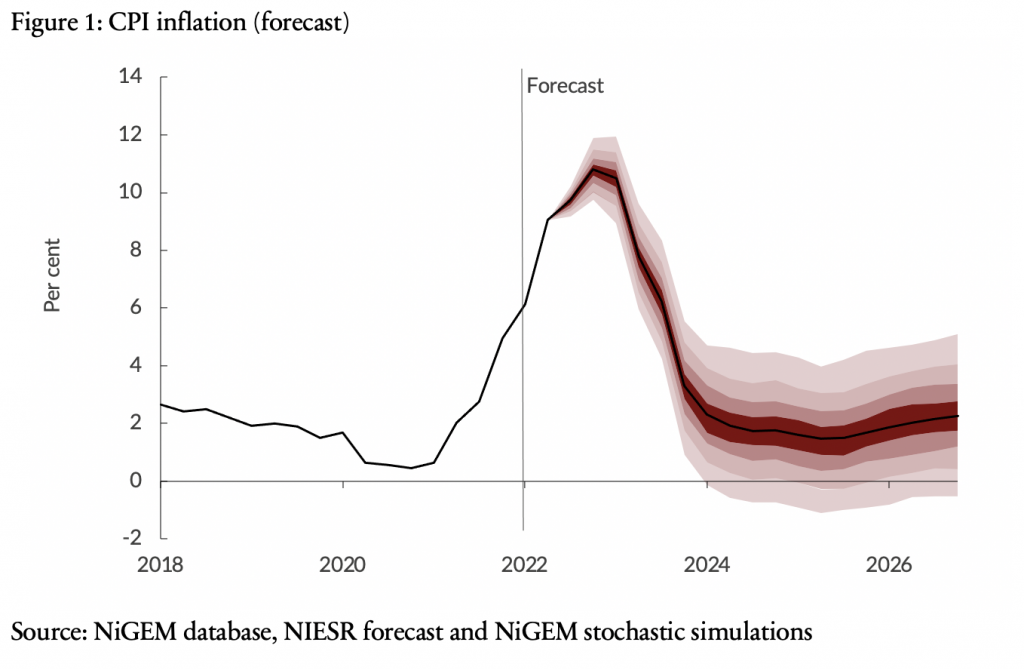

At the same time, our forecast of CPI inflation peaking at close to 11 per cent is slightly more optimistic than the Bank’s forecast of a 13 per cent peak. In our central case, CPI inflation peaks at 10.8 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2022. A combination of slowing growth in international energy prices, monetary tightening, wage restraint and falling real incomes sees inflation fall to 3.3 per cent by the end of 2023. Our central case scenario is based on the assumption that the MPC raises its Policy Rate gradually, reaching 3% in May of next year.

Regardless of whether NIESR or the Bank proves to be more accurate in its prediction, what is certain is that the Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee will continue to walk a fine line between tightening policy too quickly and so worsening the recession, and too slowly, which risks high inflation becoming embedded in expectations.

In addition to raising interest rates, the Bank of England will no longer reinvest maturing assets held within its Asset Purchase Facility and has indicated that it could begin asset sales after its meeting in September. The move to ‘quantitative tightening’ will shrink the Bank’s balance sheet and play a complementary role to interest rate hikes, potentially allowing for a more gradual rise in the policy rate. Though some have argued that the effect of quantitative tightening on demand and inflation is likely to be small, it could be a less painful form of tightening for households, given their exposure to increased interest rates, particularly at a time of headwinds from fiscal policy and higher energy prices.

Given the high and rising inflation, together with its price stability mandate, the Monetary Policy Committee has no choice but to rein in inflation by raising interest rates, embarking on quantitative tightening, and concentrating on communicating its stance over time more clearly. But who will support living standards? It has to be the government. Fiscal policy was loosened by then Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak in May, but this will not have prevented real incomes falling again. With the energy price cap rising again in October, further support is likely to be needed. Immediate support to those most adversely affected by the substantial hike in energy prices would be better directed through targeted transfers.

The government’s measures announced on 26 May to support the most vulnerable households during the cost-of-living crisis, especially the conversion of the £200 energy loan into a non-repayable £400 energy grant and the one-off cash payment of £650 to around 11 million households definitely helped. But these measures should have come sooner, and more needs to be done. As the energy price cap is lifted in October to £3,549 for an average household and food prices show no signs of stabilising, more policy mitigation will be needed. Instead of waiting for a budget in November or focusing any emergency budgets on tax cuts that do not necessarily help those households most in need, the government should act now to reduce uncertainty and give the poorest some reassurance and targeted welfare support. Of the £30bn of fiscal space identified by the OBR at the time of the Spring Statement, the government has so far committed only around £20bn. In addition, revenue raised via the energy profits levy will add to the amount of fiscal space. Given that some fiscal headroom remains, NIESR has renewed its call for a Universal Credit uplift of £25 per week for at least 6 months from October 2022 to March 2023 at a cost of around £1.35bn.

A combination of remaining fiscal space and new revenue from the energy profits levy means that the government has room for manoeuvre to act now and announce further support for vulnerable households rather than leaving them to face uncertainty until budget day in November. Targeted fiscal interventions can help the poorest while also stimulating growth and leaving the MPC to get on with bringing inflation down.

__________________

Kemar Whyte is Principal Economist at NIESR.

Kemar Whyte is Principal Economist at NIESR.