Using real-time data John Gathergood, Fabian Gunzinger, Benedict Guttman-Kenney, Edika Quispe-Torreblanca, and Neil Stewart show the UK recovery in consumer spending in the second half of 2020 was geographically uneven, heavily weighted to the home counties around outer London and the South. These patterns were exacerbated during November 2020 when a second national lockdown was imposed. To prevent such COVID-19-driven regional inequalities from becoming persistent we propose the government introduces temporary, regionally-targeted interventions (e.g. business tax relief, travel vouchers, local government transfers) in 2021.

Over the last few decades, developed countries have experienced inequality in economic growth at the regional level, with some regions not only experiencing less of the economic boom, but also having longer-lasting pain from economic busts. Emerging evidence shows that, in many dimensions, the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated existing inequalities, thereby presenting greater challenges to governments seeking to equalise the distribution of economic activity.

A recent UK government aim is to address such disparities through policies to `level-up’ the regions that historically have experienced less benefits arising from globalisation and national economic growth. This is a particularly pertinent issue for the UK, which is among the most geographically unequal developed economies.

In our research, we use granular, real-time data on consumer spending to measure the uneven 2020 recession and recovery across UK regions. We use transaction data provided by Fable Data – which we have previously used to analyse the effects of the June-September UK local lockdowns on consumer spending. Fable Data record hundreds of millions of transactions by anonymised consumers and small and medium-sized businesses across Europe from 2016 onwards and its real-time structure permits research to inform current policymaking. When aggregated, Fable’s transaction data provide a highly correlated, leading indicator of official statistics (we find correlation coefficients with Bank of England and Office for National Statistics data of 0.91 and 0.87 respectively).

What regional patterns do we see emerging across the UK?

Our headline result is that, while there has been an overall recovery in spending as ‘pent-up’ demand has been realised, there is significant geographical variation in the recovery. Aggregate spending recovered from a low of a year-on-year decline of 29% in April 2020 to year-on-year growth of 12% in October 2020. Such pent-up demand may be a combination of the lifting of restrictions, consumers becoming more confident of spending given reduced fear of the virus and improved economic prospects, or increased fatigue leading to less compliance with restrictions.

We find three key results relating to the geographical variation in recovery.

North and South

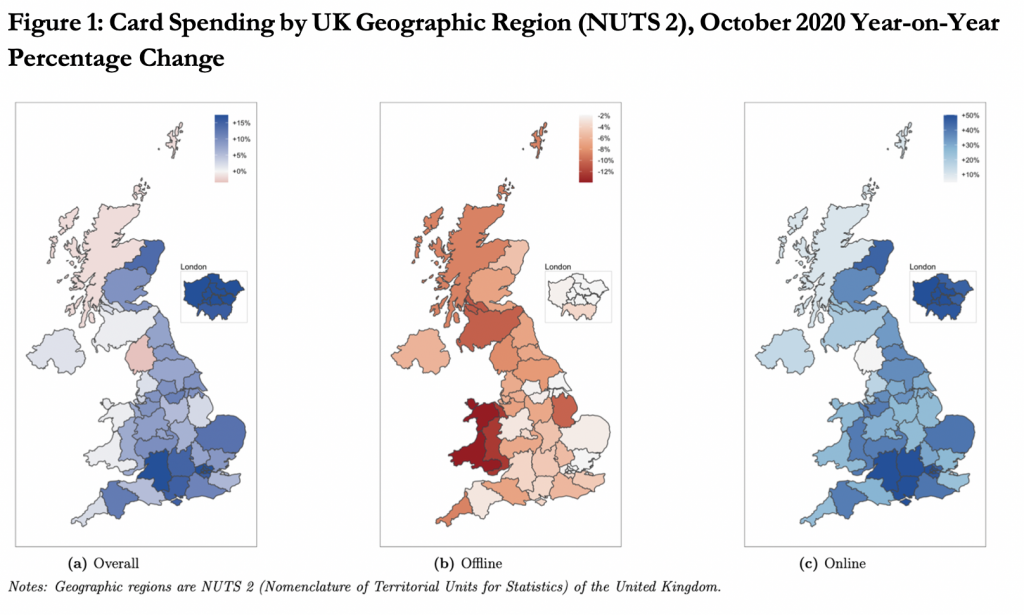

First, as shown in Figure 1, the recovery in consumer spending has been faster in the South and the home counties surrounding London. In contrast, the Midlands, Wales, the North East and Scotland show the weakest year-on-year growth; in the latter two cases, there is close to no year-on-year growth at all.

Moreover, the faster recovery in the South of England and the eastern and western regions is strongly driven by faster growth of online card spending. Notably, within England the fastest year-on-year growth is in the outer west area of London, the South West and Eastern England – areas characterised by highly affluent communities and a high level of ownership of second homes. This suggests that, to a degree, spending growth is strongest in the areas of the UK where many people are working from home or potentially working from their second home.

Cities, towns and countryside

Second, the speed of recovery has been fastest outside large cities, in commuter towns and affluent semi-countryside conurbations. In particular, the recovery has been the fastest and strongest in `business, education and heritage centres’ – such areas are popular domestic tourist destinations and thus this is in line with consumers substituting foreign for domestic holidays. Recovery has been less strong in `countryside living’ – predominantly rural areas but still noticeably stronger than other, more urban, areas.

Tiers

Third, we show that as of the end of November 2020, the point when the second national lockdown was coming to an end to be replaced by the introduction of a revised ‘Tier’ system defining levels of restrictions across geographies, the highest tier areas (‘Tier 3’) had experienced a much slower recovery in year-on-year spending, compared with the mid-tier areas (‘Tier 2’). Almost no regions were classified in Tier 1.

Tier 2 and Tier 3 areas exhibit similar year-on-year growth rates in card spending in April and July 2020 (the period before this tier system came into operation). But by October, this pattern diverges, with a stronger recovering in overall spending in the Tier 2 areas compared with the Tier 3 areas. This divergence persists through November 2020, with localities facing the UK’s new tighter Tier 3 restrictions (mostly the Midlands and northern areas) showing 38.4% lower year-on-year growth in overall spending compared with areas that, until recently, were facing the less restrictive Tier 2 (mostly London and the South).

What policy options are available to governments?

The challenge to government policy posed by COVID-19 is that the effects of the pandemic exacerbate existing inequalities in the economy. Addressing regional inequalities that have persisted in the UK for decades is a hard problem with no quick fixes. But targeted and temporary regional government interventions in 2021 may be able to rebalance the 2020 inequalities before they become entrenched. Interventions could be introduced in 2021 once the virus outbreaks are under control and vaccinations have been more broadly rolled out.

The ability to measure regional economic data in real time offers exciting potential to inform when, where and how to target regional policy interventions and then to evaluate their effectiveness rapidly to decide whether to expand, modify or remove such measures in a cost-effective way. This is a more nimble strategy than traditional government approaches of typically applying policies at a national level with limited abilities to assess their impact.

What form could such measures take? Given the clear effects of online spending on offline retailers in particular locations, providing relief to such businesses can help to sustain them and enable them to pass through savings to increase demand for their business. This could take the form of business rate relief or VAT cuts based on store location.

Given some regions have recovered rather well, providing incentives to encourage residents in those locations to visit harder-hit parts of the UK could be an effective way to generate spending in depressed areas. One method for doing so would be providing vouchers for discounted travel and to spend in particular destinations, potentially through a lottery system to enable some individuals to have large incentives to do so.

A less centralised approach would be for national governments to make temporary funding available to local governments. This could be done in proportion to how adversely such regions have been affected by the crisis and adjust the duration and amount of funding to local authorities based on real-time indicators.

Other areas may consider forms of spending to be more efficient, such as funding local events or services or initiatives targeted at providing relief to socio-economic groups of people most adversely affected by the pandemic. We hope our research will prompt public discussion on other types of measures that could be feasibly implemented and evaluating their merits.

_____________________

Note: the above draws on the authors’ paper, ‘Levelling Down and the COVID-19 Lockdowns: Uneven Regional Recovery in UK Consumer Spending‘. This research is supported by the UK Economic and Social Research (ESRC) under grant number ES/V004867/1 ‘Real-time evaluation of the effects of COVID-19 and policy responses on consumer and small business finances’.

John Gathergood is Professor of Economics, University of Nottingham.

Fabian Gunzinger is a Behavioural Science PhD at Warwick Business School.

Benedict Guttman-Kenney is an Economics PhD at the Booth School of Business, University of Chicago.

Edika Quispe-Torreblanca is a DCC Career Development Fellow at Said Business School, University of Oxford.

Neil Stewart is Professor of Behavioural Science at Warwick Business School.