Will Tanner argues that if the Prime Minister is serious about his ‘tough but intelligent’ approach to crime and justice then resources should be directed to what is proven to work. The astonishing success of the Violence Reduction Unit (VRU) in Glasgow is just such a project. Only through such localism could initiatives like the VRU become the norm.

Will Tanner argues that if the Prime Minister is serious about his ‘tough but intelligent’ approach to crime and justice then resources should be directed to what is proven to work. The astonishing success of the Violence Reduction Unit (VRU) in Glasgow is just such a project. Only through such localism could initiatives like the VRU become the norm.

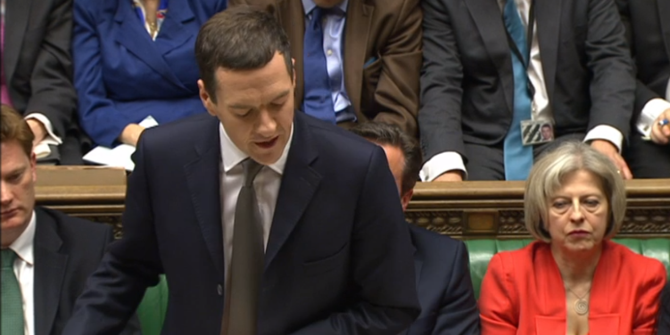

Last week, in his first speech on law and order since entering office, the Prime Minister unveiled a new organising principle for the Government’s approach to crime and justice: “tough but intelligent”. The slogan may lack panache, but the principle – that policy must be guided by evidence of “what works” as well as public opinion – stands truer now more than ever. In a time of straitened finances and increasingly complex demands, precious resources must be directed to where they will have the most impact on outcomes.

In criminal justice, this means shifting the emphasis towards preventing crime before it has been committed, and away from reacting to criminality after the fact. The UK currently has the most expensive criminal justice system in the world, spending more as a proportion of GDP than any country in the OECD. Yet the latest reoffending figures, released by the Ministry of Justice last week, show nearly half of all prisoners going on to commit further crimes, and rising. The challenge for public services is to translate policy aspiration into practical action to deliver more for less. As Reform’s recent report, Doing it justice, shows, the answer lies in joining up criminal justice services to deliver a seamless, end-to-end service. One initiative shows how it can be done.

A decade ago, Glasgow topped all of the wrong rankings. In 2001, rates of violent crime overtook those of New York for the first time, having been half that of the Big Apple just five years earlier. The number of murders was three times the Scottish average, and more than double that of most major European cities. Endemic public health problems, including an alcohol-related mortality rate of four times the UK average, also prevailed, compounding criminal behaviours.

In 2005, John Carnochan, a Detective Chief Superintendent with Strathclyde Police, and Karyn McCluskey, a former nurse, decided to do something about it. As Karyn McCluskey says, “We had looked at our violence problems and decided that what we were doing wasn’t working and that we had to do something radically different.” The result was the Violence Reduction Unit (VRU), a multi-disciplinary initiative dedicated to tackling violent crime through prevention and collaboration.

The stick of tough enforcement is combined with the carrot of social and clinical support. Gang members approached by the VRU are told two things: firstly that there will be a zero-tolerance police response if the violence doesn’t stop, which will impact every gang member, whether they were involved in the event or not; and secondly, that they will be given substantial help with housing, education, training and employment if they go straight.

The VRU brings together previously disparate agencies in a joined up way; local police, health, education, housing and social services work together to deliver preventative interventions, from community work to talks in schools. Intelligent practice is informed by data. The VRU has pioneered the sharing of relevant information in order to build up a more accurate picture of violent crime. Local A&E departments, for example, now share injury data with local police, revealing not only the locations of violent crimes, but that 49 per cent of incidents go unreported. Local train and bus companies share information on which routes are commonly vandalised by knives to allow the police to target resources most effectively.

Seven years later, the VRU has been credited with an astonishing turnaround in Glasgow. Since 2006, crime has fallen by a fifth, including a 38 per cent fall in violent crime. Rates of serious assaults and robbery have both declined by more than 40 per cent. Of over 400 gang members contacted by the VRU since 2008, three quarters have pledged to give up violence and 100 are now in full-time employment, work or training. Violent offending among the group has fallen by nearly half. Last year, Glasgow was named the safest city in the UK for personal safety, and one of the safest in the world.

Glasgow is currently the exception; it needs to be the rule. On 15 November, the election of Police and Crime Commissioners (PCCs) will bring with it a ready-made framework for criminal justice integration across England and Wales. With wider powers over other services, such as prisons, probation and emergency services, PCCs would be well-placed to drive the type of integrated delivery that has transformed the streets of Glasgow. With a single, pooled budget and end-to-end oversight, commissioners would be incentivised to spend where they will get the most bang for their buck, such as prevention, and pass on the savings to their electorates through local taxation. In fact, without power over preventative services as well as reactive policing, PCCs will be inherently limited in their ability to drive down crime, and may be discredited before they have even begun as a result.

The Prime Minister’s “tough but intelligent” approach to law and order has merit. However, the Government has yet to put in place the framework to make the rule rather the exception. If the Government wants to introduce a real revolution in law and order, it should follow its flagship policy to its logical conclusion and devolve powers and budgets for all criminal justice and emergency services to PCCs.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Will Tanner is a Researcher at the independent thinktank Reform, whose latest report, Doing it justice, is available at www.reform.co.uk.

Will, I read your article with interest. I am presently at Glasgow Caledonian University studying for my Ph.D in international criminal justice policy transfer. I was previously the deputy manager of the Glasgow CIRV project, prior to my retirement from Strathclyde Police. I an in Cincinnati at the moment on a research visit but would like to have a chat with you on my return to UK.

Regards