Last May saw an unprecedented victory by the Scottish National Party (SNP in Scotland, and a rout for the Conservatives. While many commentators attribute the Conservative’s decline in Scotland to the harsh economic policies seen in the Thatcher years, the IPPR’s Nick Pearce argues that the decline of Scottish Conservatism began in the 1960s when it failed to adapt to changing social and economic circumstances in Scotland.

Last May saw an unprecedented victory by the Scottish National Party (SNP in Scotland, and a rout for the Conservatives. While many commentators attribute the Conservative’s decline in Scotland to the harsh economic policies seen in the Thatcher years, the IPPR’s Nick Pearce argues that the decline of Scottish Conservatism began in the 1960s when it failed to adapt to changing social and economic circumstances in Scotland.

The stunning victory of the SNP in May’s Scottish Parliamentary elections might have been expected to trigger extensive public and political debate about the future of the United Kingdom. Thus far, it has not done so. Aside from an interesting speech by Sir John Major at Ditchley earlier in the summer, and latterly some fairly predictable anti-nationalist rhetoric from Scottish Liberal Democrats and English conservative commentators, the SNP earthquake has precipitated very little by way of political discussion about the configuration of the nations of the UK.

Instead, it has been left to Murdo Fraser, a candidate for the leadership of the Scottish Conservatives, to open up the terrain of a new political settlement for the UK, through his call for a new conservative (or reminted Conservative) party in Scotland. This has certainly set the Tory hounds racing, as they mull the implications of a separate Scottish Conservative party for the fortunes of their political clan, north and south of the border. But it has also provided a useful prism through which to think about broader political questions for the union and the fate of its main political forces.

It is indisputable that Scottish Conservatism is a moribund force. The party fell to an all-time low in the May elections to the Scottish Parliament, down 2.7% on its 2007 constituency performance, roughly the inverse of its performance in Wales, where it came second in the Assembly for the first time.

Most commentators attribute this decline to the effects of Thatcherism and long Scottish memories of what happened to their country in the 1980s. They conclude that a centrist conservative party, untainted by association with Thatcher, stands the only chance of detoxifying the conservative brand in Scotland and renewing its political fortunes.

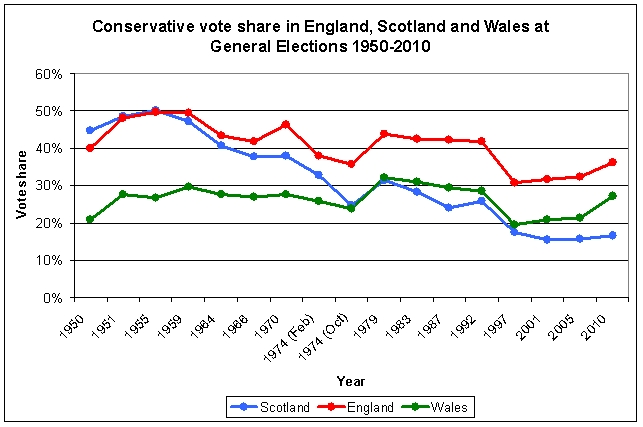

Yet the fall in support for the Conservatives in Scotland long predates the effect of Thatcherism. As the Figure One below shows, the Conservatives began to lose vote in share in Scotland in the early 1960s. Part of this fall is accounted for by the wider trend of declining vote shares going to the two main political parties but the drop is more precipitate in Scotland (particularly in the 1960s and 1980s), and there is no steady recovery seen during the New Labour years, as there is in England and Wales. Therefore to trace the roots of the current crisis in Scottish conservatism to the toxicity of Thatcherism is to paint only half the picture, since most of the loss of popular support for the Conservatives in Scotland had already taken place by the time she came to power in 1979.

Figure One

Source: Wikipedia

In fact, as the foremost historian of modern Scotland, Tom Devine, argued in his magisterial work The Scottish Nation (1700- 2007) the Conservative Party began to lose support in Scotland when its role as a Protestant party of the Union and Empire waned in the early 1960s. In 1964, it dropped the title Unionist, in favour of the anglicised Conservative. As Devine recounts, it steadily lost the skilled Protestant working class, as Britishness and sectarianism lost their appeal, while its Clydeside industrial class leaders were replaced by anglicised lairds and aristocrats. As the Scottish middle classes abandoned the cities, Labour consolidated its hold on urban Scotland, while retaining the loyalty of the Catholic working class. The SNP then profited from the Conservative decline, while the failure of devolution ambitions in the 1970s set the stage for the experience of Thatcherism and rule from Westminster, as Henry Dundas, the 18th century government overlord, was reincarnated in successive Scottish Office Ministers.

The other fact worthy of note is that Scotland was a Tory-free zone for most of the 19th century, during the years of liberal hegemony. The Conservatives won only seven seats in nine general elections between 1832 and 1868, returning no MPs at all in the elections of 1857, 1859 and 1865. The Scottish Conservative political tradition only revived as unionists gathered their forces to oppose Irish Home Rule, which was followed by the waning of liberalism in the early 20th century under pressure from the rise of class politics. Conservatism therefore has relatively shallow roots in Scottish soil.

To argue, as Lord Forsyth has done, that Murdo Fraser is just an appeaser of Scottish nationalism is therefore wide of the mark. Mr Fraser is simply revealing, very starkly (and within the context of an evolving devolution dynamic) the depths of the crisis of Scottish conservatism. Conservatism has failed to invent a new, post-Imperial identity in Scotland. Its English reinvention in the 1980s as a neo-liberal Thatcherite party did not secure consent or support from the Scottish people. Nor did it offer them a new political settlement within the union. It consequently has almost nothing distinctive to offer in Scottish politics.

In the meantime, however, the SNP has widened its political appeal. It now embraces – much as Tony Blair did in 1997 – a wide spectrum of support from left to right, across the length and breadth of Scotland. Alongside broadly social democratic voters, It picks up support from precisely those sections of the electorate to whom Conservatives would wish to appeal: the business class, private sector employees, small employers and rural interests. To imagine that this is an artefact of Alex Salmond’s political acumen and the pork barrel politics of a bloated public sector, whose challenge can be met and defeated simply by defending the union status quo, is a delusion. Scottish nationalism has modernised as a movement, squeezing out the political space that the Conservative Party and others might have occupied.

The good news for Scottish Conservatives is that both Labour and the Liberal Democrats are suffering their own existential crises in Scotland, albeit ones that have come upon them with the shocking velocity of sudden electoral defeat, rather than gradual decline. Labour has atrophied as a party – intellectually and organisationally – since devolution and that process of decay has now caught up with it, while the Liberal Democrats have been punished for being precisely the kind of political party in Westminster – socially and economically liberal – that a smaller, niche conservative party might have sought to become in Scotland. Mr Fraser’s agenda therefore raises the bar for the reinvention of the political identities of all the main unionist parties in Scotland, not just the Conservatives.

The final intriguing prospect opened up by Mr Fraser’s intervention is whether it will stimulate more debate on the English question – or more specifically whether the logic of separate Scottish political identities will be followed into English party formation.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

This article first appeared on Nick’s Blog at the IPPR on 6 September.

Thanks, very interesting.

On my own blog (http://scotip.wordpress.com/), I’ve just been discussing the need for a new Scottish right of centre party. The reason is entirely practical. I am generally pro-(real) business, but pro-environment, pro-public NHS, Schooling and anti-nonsense PC. I suppose pro-business but not enough to be anti- (key) public services.

For various reasons I found myself at the heart of UKIP Scotland last year. The first surprise was that I was far from alone in my politics – yes to the left, but not at the extreme left as the public PR had suggested.

But being elevated to work at the top, it quickly became painfully obvious that whilst the party hardly had the premier political team, what it did have were having to work with both hands tied behind their backs. Because no matter how hard they tried, they were constantly being undermined by the “absentee landlords” down in England. And the problems that created were clearly discouraging more serious people from joining and/or taking an active role.

The visit to Edinburgh was typical. Whilst the way Nigel Farage was treated was appalling and I was sickened by the behaviour of Alex Salmond who was a disgrace to Scotland, now I’ve left UKIP, I can say that Nigel was not at all sensitive to the politics of Scotland and after his flying visit he completely ignored us in UKIP Scotland who ended up having to deal with all the shit which was flying as a result of Farage.

It really was very bad, with many UKIP members being afraid they would be physically injured if they went out in public.That was a direct result of Salmond’s legitimization of violence.

But this was just one of a host of other problems. The key issues in Scotland are very different from those in England. But could those who ran the party in England see that? No! Would they listen to us in Scotland, No! Would they give us the support and finance to tune the policies and presentation to fit the Scottish context – not on your nelly!

UKIP Scotland’s role was only as voter & funding “fodder” to support English tailored policies – devised by the English, for the politics of English, and which I could see would just increase the disparity of political and economic benefit for Scotland.

The result is that UKIP looks like a bunch of insensitive Nazis – worse than anything seen in the EU.

But upon reflection, it is the same with the Tories. having lived in the SE of England and even standing as a Councillor, I can see why someone in the SE of England and particularly London would love them – but I can’t see much relevance at all to us in Scotland. And personally, I am still angry with the Tories for the way they intentionally destroyed Scottish industry. Reform yes! Destruction no! Their policies caused huge and unnecessary damage to Scotland. If Thatcher had been Scottish, she would have understood that. She wasn’t and the damage she did caused huge and long-term social and economic harm in Scotland. Scotland cannot afford to have another Thatcher government!

So, I think the fundamental problem for the right in Scotland – is that all right of centre parties end up being run from England and however noble their intentions, their carelessness and inconsideration for us in Scotland ends up making them look like heartless Nazis to us.

So, my diagnosis is very simple: the only way to rebalance Scottish politics is to have a new Scottish right of centre party and this is what I suggested in my last article (http://scotip.wordpress.com/2014/03/25/a-new-scottish-right-of-centre-party/)