Much has been written about the economic costs of our most recent recession. However, what were its social costs? How did the civic wellbeing of individuals and our communities fare? James Laurence finds the UK suffered a social recession alongside the economic one, with volunteering behaviour declining sharply following the crisis in 2008.

Much has been written about the economic costs of our most recent recession. However, what were its social costs? How did the civic wellbeing of individuals and our communities fare? James Laurence finds the UK suffered a social recession alongside the economic one, with volunteering behaviour declining sharply following the crisis in 2008.

Back in 2009, despite the darkening clouds of redundancy and unemployment, stories proclaimed that the recession was rekindling our nation’s ‘blitz-spirit’; that the shared-hardship of our times was leading to a ‘flourishing’ voluntary sector and to ‘rediscovering the joys of good old-fashioned neighbourliness’. History, however, was teaching us another lesson.

The ‘Great Depression’ of the 1930s saw a precipitous drop in membership of organisations in the US, while the classic sociography of Marienthal charted the complete civic-collapse of a community under enduring hardship. How then did we respond to the ‘Great Recession’ of 2009? With open arms or bowed heads?

To unpick this puzzle my colleague, Chaeyoon Lim, and I turned to the 2001-2011 Citizenship Survey. This is a large, nationally representative survey of England and Wales, sampling over 100,000 people, and gathering detailed data on residents’ social and civic behaviours. Between 2001 and 2005 this was conducted every two years. However, from 2007 onwards it switched to being collected quarterly. This provided an unparalleled opportunity to finely track civic behaviours before, during and after the recession.

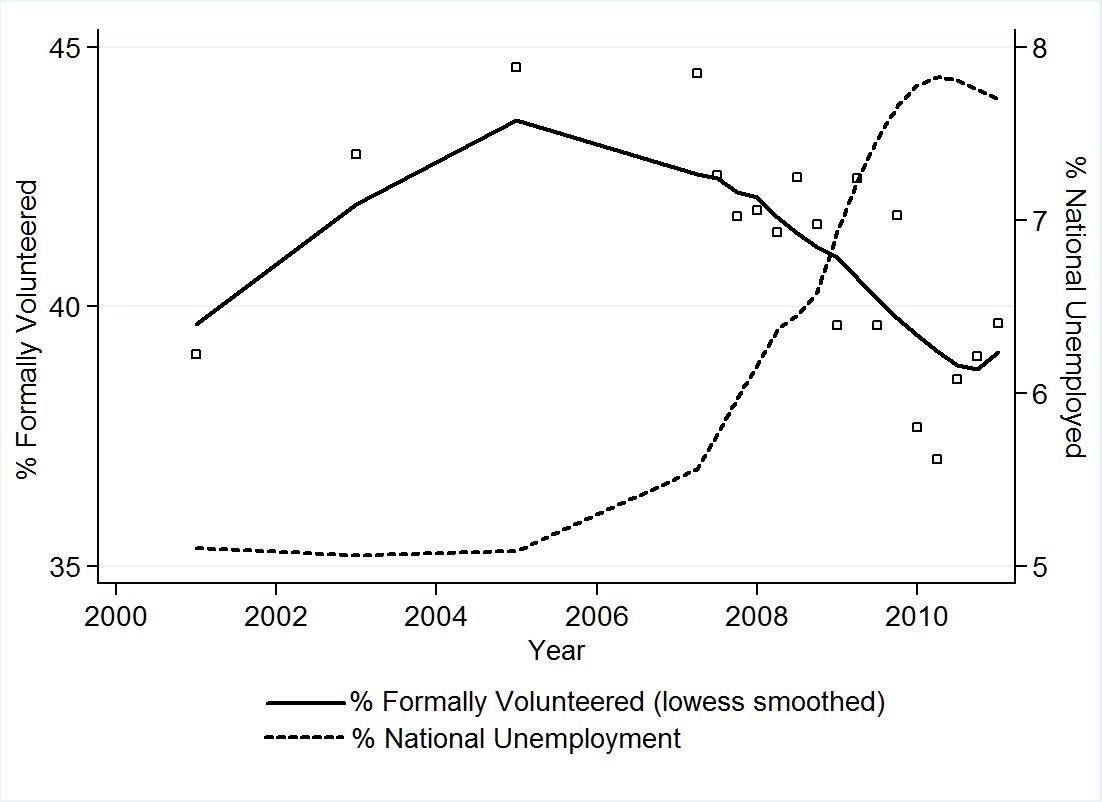

So, what did we find? Far from ‘flourishing’, we found that alongside the economic recession, the UK also appeared to suffer a ‘social recession’. Between 2008 and 2011, formal volunteering – that’s all unpaid help given to or through organisations – sharply declined by around 6 per cent to its lowest levels since 2001 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Change in those formally volunteering (%) and change in unemployment (%)

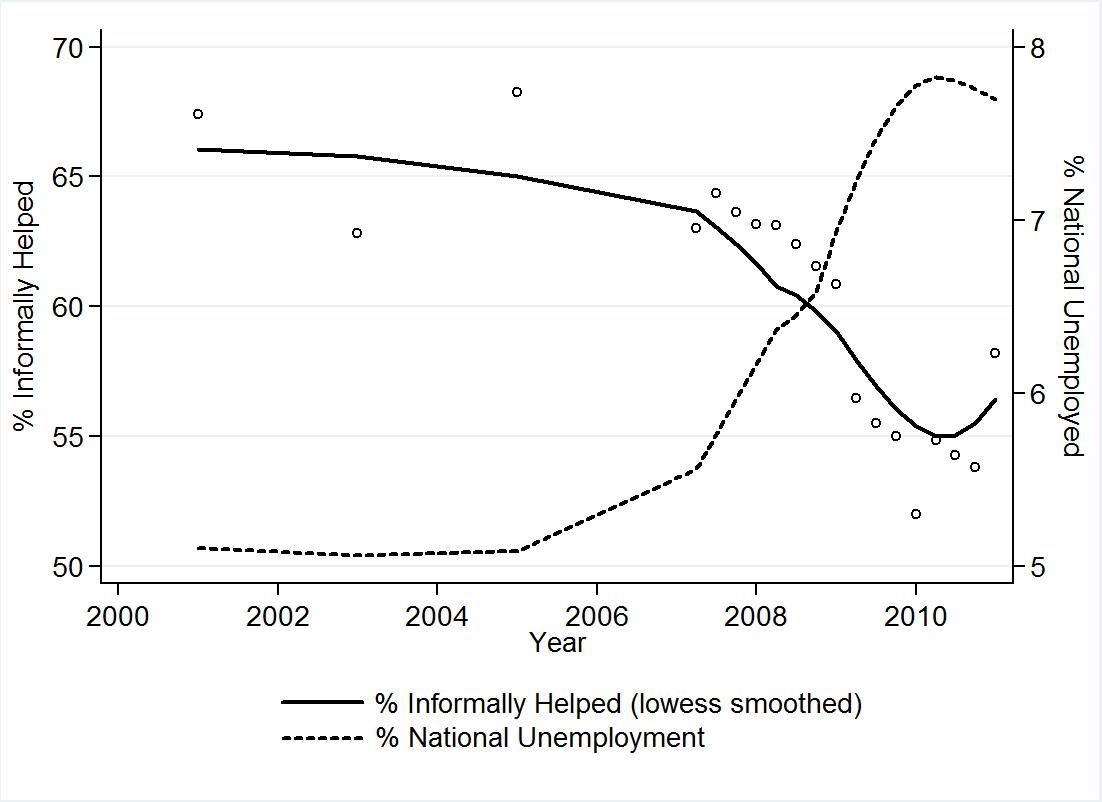

One possibility was that people may have been less able to commit their time and energy to organisations; instead, help may have shifted to friends and neighbours in their more immediate proximity. However, the proportion providing informal help – that’s the kind of day-to-day help given amongst friends and neighbours – crashed by around 12 per cent in the space of around two-years (Figure 2). This kind of decline is normally seen over decades and between generations.

Figure 2: Change in percentage providing informal help and change in unemployment (%)

What led to this civic withdrawal? Our first thought was that helping behaviours declined simply because more people were experiencing economic hardship. Those experiencing hardship, such as the unemployed or those with low household incomes, did volunteer less. However, controlling for economic hardship in our models did little to explain the trends.

The national declines in volunteering could have been driven by civic withdrawal amongst the most disadvantaged in society, less capable of absorbing the shocks of the recession. However, we found similar declines in helping behaviours across all income groups, employment statuses, education levels and social classes.

Economic hardship amongst individuals alone therefore struggled to explain why civicness was suffering so much. Instead, the key factor that determined just how people responded to the recession was how disadvantaged their community was.

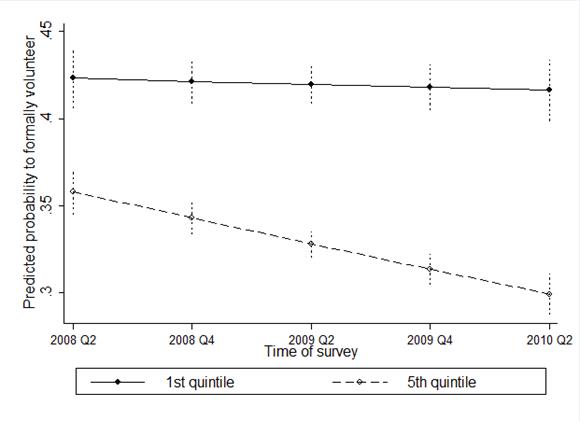

Behind the national trends stark differences emerged in how different communities weathered the recession. In the 20 per cent least disadvantaged communities, rates of volunteering for organisations barely registered the recession at all, remaining remarkably stable. However, in the 20 per cent most disadvantaged communities, volunteering in organisations declined by nearly 7 per cent (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Change in formal volunteering by income quintile

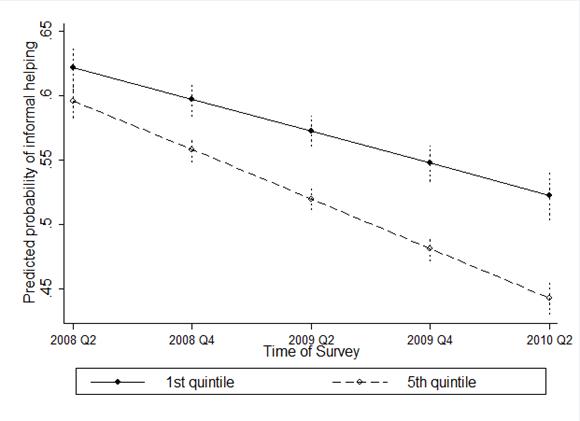

A similar pattern emerged for informal helping. The least disadvantaged communities saw some decline, with levels dropping by 7 per cent. However, in the most disadvantaged areas, in the space of about 2 years, 15 per cent (that’s over 1 in 7) fewer people were engaging in informal helping (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Change in probability of providing informal help by income quintile

The result of this: the recession substantially widened gaps in rates of formal volunteering between the most and least disadvantaged communities, as well as prising open new gaps in levels of informal help where previously there were none.

So, why did residents of disadvantaged communities experience such a withdrawal from civic life? One reason your community matters for helping behaviours is its social resources – the trust and norms of reciprocity amongst residents – which draw people into networks of participation. Disadvantaged communities, through things like higher turnover, crime, limited spaces of interaction, often possess a deficit of such networks.

Under the stresses and pressures of a recession, these networks might become increasingly important; not just for retaining volunteers, but for organising support in the face of adversity. To explore this we looked at whether trust amongst neighbours acted as a buffer to the impact of the recession.

We found that helping behaviours declined far less amongst those reporting higher trust amongst neighbours. Moreover, the greater decline in helping behaviours amongst the less trusting accounted for a good part of why help declined more in disadvantaged areas. With fewer social resources available, disadvantaged communities, that were hit hardest by the recession, were also the least able to absorb those shocks, suffering the greatest drop in civicness.

In spite of all this, there is some good news. The economy is beginning to return to pre-recession levels, and though it is still early days, there is some evidence that civic behaviours are recovering too. Informal help is slowly climbing back to its rates before the recession. Volunteering through organisations has also reclaimed some ground (although this recovery has been choppy). Yet, what still remains to be seen is whether we are all sharing in this recovery; or, are the most vulnerable communities, which bore the economic and social brunt of the recession, still counting its costs.

Note: For more on this research, see Doing good when times are bad: volunteering behaviour in economic hard times by Chaeyoon Lim and James Laurence in The British Journal of Sociology.

James Laurence is an ESRC Future Research Leaders Fellow at the Cathie Marsh Institute for Social Research and Department of Sociology at the University of Manchester. His current project, the ‘Spatial and Temporal Dynamics of Ethnic Diversity, Socio-Economic Inequality and Social Cohesion’, explores the role of ethnic diversity, immigration and inequality in the creation and dissolution of social capital, cohesion and inter-group relations. His other research interests include the impact of micro- and macro-scale economic hardships for social, civic and political attitudes and behaviours, and ethnic-inequalities in violent crime.

James Laurence is an ESRC Future Research Leaders Fellow at the Cathie Marsh Institute for Social Research and Department of Sociology at the University of Manchester. His current project, the ‘Spatial and Temporal Dynamics of Ethnic Diversity, Socio-Economic Inequality and Social Cohesion’, explores the role of ethnic diversity, immigration and inequality in the creation and dissolution of social capital, cohesion and inter-group relations. His other research interests include the impact of micro- and macro-scale economic hardships for social, civic and political attitudes and behaviours, and ethnic-inequalities in violent crime.

Interesting findings and analysis. However, you are discussing England & Wales not the UK. Indeed the Scottish Household Survey shows no change over 2007-12 (http://www.volunteerscotland.net/policy-and-research/data-and-graphs/trends/); as ever definitions and questions tend to vary. Couldn’t source NI comparable data unfortunately.

I would suggest that the Great Recession left a financial along with a psychological impact on people, and their lives.

As someone who have volunteered since 2012 as a consultant for a CIC, mentor for job seekers – NEETS and graduates… I, like many, would feel disingenuous that the development of such vital skills are left unharnessed by the Non-profit sector.

Stemming from a strong career background in management, business start-up and an advisor – all in the private sector, one would have thought that this vital balance of skills from both sector was key to developing the NFP sector. However, it doesn’t seem so. I acknowledge that having “won the confidence” from directors in the private sector, the Charity sector seems not willing to connect “talent” like myself with senior managers and directors – as a way of improving staffing and business opportunities.

With all this in mind, I am no doubt that volunteering is at an all time low – as the Non-profit sector needs to do more to captivate “talent” and acknowledge that this differs from a skills-based application as it is much more in-depth towards creativity and development. Maybe, this is what employers fear.

During the “Thatcher Years” of unemployment, I noticed how much more friendly neighbours toward helping each other. This is the opposite trend to what is described here. So it strikes me that the reason for a decline in volunteering with greater unemployment as shown in the first two graphs is an economic one. As a volunteer I would travel to my place of work and pay for the ride from my own pocket. Pride of not, I refused to claim this expense from the organizers of the place where I worked, because I regarded the fares as a part of my contribution to the cause that I was helping to support. Yet somehow your article does not mention the economic aspects of the volunteer when giving in this way.