As soon as Gordon Brown left office, Labour began to critique its own legacy in government. Glen O’Hara explains the impact of Ed Miliband’s criticism of his predecessors, and the long-term effects of that approach.

As soon as Gordon Brown left office, Labour began to critique its own legacy in government. Glen O’Hara explains the impact of Ed Miliband’s criticism of his predecessors, and the long-term effects of that approach.

It’s impossible to begin any assessment of Labour’s last period in office without reference to the idea of ‘neoliberalism’. In many ways that critique is exaggerated, though it contains elements of truth. The state intervened more in economic and social life; the public sphere was better funded; governments’ focus drew ever tighter on liberating children and the elderly (in particular) from poverty. Even so, many of the techniques which Labour used to deliver better public services drew on practices – or investment – from the private sector. Their incrementalist political language, and the way it imagined a cautious electorate selecting between teams of managers delivering ‘results’, often gave the impression that the Party was much more conservative than it really was. It is little wonder that critiques of the economic settlement we have known since the mid-1970s have attached themselves to New Labour just as they have the Conservatives.

But the process by which New Labour came to be seen as ‘neoliberal’ are as rooted in the vagaries of politics as they are down to the reality of policymaking between 1997 and 2010. In particular, once New Labour left office, the Labour Party itself very quickly began to critique its own very recent past. Ed Miliband’s opposition to the Iraq War, in particular, allowed him to distinguish himself from the Blair years more successfully than his brother David. His criticism of capitalism, and his emphasis on equality, undoubtedly seemed sharper than his main rival.

The younger Miliband chose, in his very first interview as leader, to differentiate himself from the Blair and Brown years. As he put it: ‘the era of New Labour has passed. A new generation has taken over’. While in and of itself an inevitable and necessary indicator of new directions and novel policies, Miliband’s stress was placed very much on his rejection of ‘Blairism’ as a way of conducting politics, rather than his own approach: heavier taxes for higher earners and a halt to public sector pension reforms were high up his list of priorities.

To begin with, this new language seemed as if it would be merely a matter of emphasis, and need not particularly matter anyway: Labour would pivot towards the Brownite agenda that the younger Miliband had stood by while in office, remaining a Left variant of New Labour that could be electorally successful after only a short period out of power. For most of the 2010-15 Parliament, Labour’s usual civil wars in Opposition – which burst out in the early 1950s, 1970s, and 1980s – were stilled as Miliband mostly successfully walked a tightrope between the Right and Left of the Party. The Liberal Democrats’ declining popularity while in coalition with the Conservatives seemed to offer Labour an easy way back to power as they swept up Left-leaning ex-Liberal Democrats, and for almost that entire period Labour was indeed ahead in the polls. At the mid-point of the 2010-15 Parliament, for instance, they led the Conservatives on average by between ten and eleven percentage points.

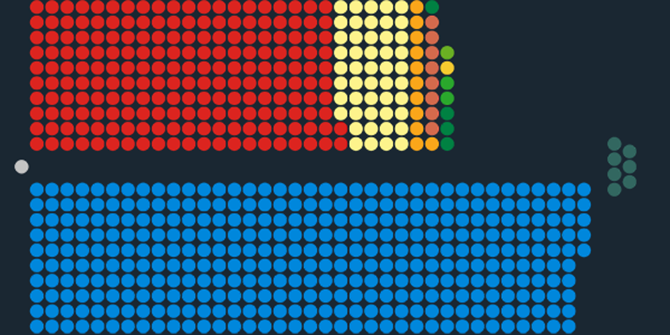

It was only in 2015, after a shattering and mostly unexpected defeat – especially given the scale of Labour’s losses in Scotland – that the long-term effects of Ed Miliband’s break with the Party’s immediate past became clear. Miliband had effected a crucial transformation in the party’s internal character, and in this sense he has rightly commented himself that he formed the vital ‘bridge’ between Blairism and Corbynism. The membership, which in 2010 had opted for his older ‘Blairite’ brother David by a margin of 44% to 30% in the first round of voting (and 56% to 44% in the final round), had now firmly shifted towards Labour’s new rhetoric of anti-austerity and anti-‘cuts’ campaigning.

The new atmosphere Miliband had created took a while to become evident: but the failure of his own balancing act rapidly uncovered the changes his leadership had wrought in the internal mechanics of Labour thinking. The Party’s MPs found that their equivocation on the Conservatives’ Welfare Bill in the summer of 2015 damned them in most members’ eyes as amoral trimmers, interested only in managing rather than transforming capitalism. Miliband’s rhetorical rejection of the New Labour years, which he perhaps intended as a recrudescence of campaigning social democracy, had opened the door to a thorough-going revolution in the Labour Party’s affairs.

Miliband’s internal party reforms gave this momentum a further push. As part of wider-ranging reforms to Labour’s trade union links, a package of reforms recommended by Ray Collins – a previous Labour General Secretary – led almost by accident to a fundamental change in the very nature of the Labour Party itself. Trade unionists were now to opt in to Labour membership, rather than being counted en masse via the political levy; as part of this democratisation, the three-part electoral college of MPs and MEPs, trade unionists and party members would be abolished in favour of an all-in contest held under one member, one vote for all.

The unintended consequence of this review was that the veteran left-wing campaigner Jeremy Corbyn, who had never held any Party office at all during 32 years in Parliament, won the leadership election of 2015 at a canter, attracting 59% of the vote even in the first round. That victory seems much less likely had Labour’s membership remained as it was in 2010, and virtually impossible if the electoral college of MPs and MEPs, members and trade unionists had remained in place.

This is, at best, a sketch of a contemporary history that is still in train. What is important in terms of our view of New Labour is that the Miliband interregnum, and most recently Corbynism’s radical break with recent Labour history, are both now obscuring the actual course of events and policy in the Blair and Brown years. Those administrations’ record is complex, multifaceted and contested: most governments’ legacies are fiercely and properly debated. But the vitriol now reserved for both is bizarre when we consider their extraordinary efforts and successes on Britain’s relations with the rest of the European Union, devolution, Northern Ireland, child and pensioner poverty, National Health Service funding, school results, inner-city regeneration and crime.

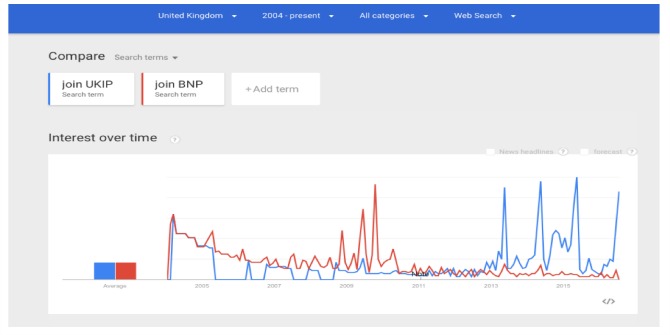

That deep opprobrium has many causes. The collapse of confidence that began with the war in Iraq, and accelerated after the financial crash and parliamentary expenses scandal, seems to have brought all established politics into disrepute. The Conservatives found it fairly to disassemble many (though not all) of Labour’s social policy initiatives, again casting a pall over the hopes placed in any positive public policy. Retreating faith in all institutions, and the corrosive and divisive effects of social media disputation, are making it harder and harder to reach any consensus. But one reason for New Labour’s plunge from grace on the Left is a contingent question of politics, and of language: the rupture that Miliband and Corbyn themselves have announced with Labour’s recent past.

___________

Glen O’Hara is Professor of Modern and Contemporary History at Oxford Brookes University. He is the author of a string of books and articles on recent British history, including The Paradoxes of Progress: Governing Post-War Britain, 1951-1973 (2012) and The Politics of Water in Post-War Britain (2017). He blogs at ‘Public Policy and the Past’, and tweets as @gsoh31.

Glen O’Hara is Professor of Modern and Contemporary History at Oxford Brookes University. He is the author of a string of books and articles on recent British history, including The Paradoxes of Progress: Governing Post-War Britain, 1951-1973 (2012) and The Politics of Water in Post-War Britain (2017). He blogs at ‘Public Policy and the Past’, and tweets as @gsoh31.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Pixabay/CC0 licence.

At root is the left’s habitual disappointment with what a Government is actually capable of achieving. Labour has “form” in this respect, so we currently have the latest incarnation of a well established principle

The membership composition and vote reflects the current state of the Party in the short term. It is not stable. Conservative policy types dominate when in Govt, radical Lefties when in opposition. The latter leave the scene when in Govt. So the members vote in 2010 should not be seen as a statement of the long term situation. Historically the CLP’s always voted for the Left ticket for the NEC since the time of Ian Mikardo and Tom Driberg.