Over 24 million people are now unemployed in the EU, with 5.5 million under the age of 25. Robert Plummer argues that this unemployment is a paradox given that young people have never been so well educated. The EU and its Member States must now push for youth apprenticeships to give young people practical professional experience to help get them into work.

Over 24 million people are now unemployed in the EU, with 5.5 million under the age of 25. Robert Plummer argues that this unemployment is a paradox given that young people have never been so well educated. The EU and its Member States must now push for youth apprenticeships to give young people practical professional experience to help get them into work.

This article first appeared on the LSE’s EUROPP blog

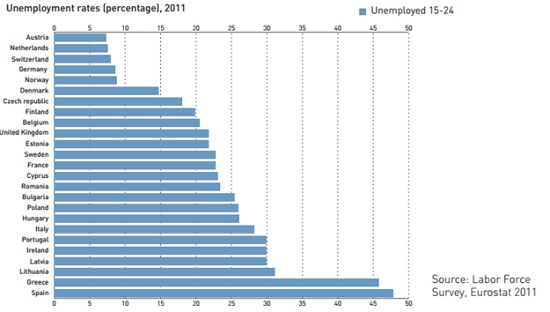

Europe’s financial crisis has taken on a distinctly social dimension. This is witnessed in the rising levels of unemployment across Europe, especially among young people. There are currently over 24 million unemployed people in the EU, including 5.5 million under 25 years old. To make matters worse, a total of 7.5 million young people are neither in employment nor in education or training. These are alarming figures, and even before considering that in Greece and Spain youth unemployment is now approaching 50 per cent, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 – Youth unemployment in Europe

The youth paradox

In today’s climate, going through school education, and even university, does not guarantee a smooth transition into working life. Young people have never been more educated than they are today, with a larger share continuing into tertiary education than in previous decades. At the same time, there are presently 4 million unfilled vacancies in the EU.

In other words, this generation of young people should constitute a highly sought after influx of creativity and modern skills to the labour market. Yet high levels of youth unemployment in many EU member states stand in sharp contrast to the potential of the younger generation. This represents what can be called a ‘youth paradox’ and shows that something is seriously wrong in both the functioning of our education systems and our labour markets.

Access to a sufficient and skilled workforce is one of the main challenges facing European businesses and countries for the years to come. In this respect, labour market needs should be at the centre of education. An efficient education system is needed for a well functioning labour market. Notably, improving the quality and status of apprenticeships is essential.

Evidence suggests that well functioning apprenticeship systems contribute to companies’ competitiveness and at the same time they appear to correlate to low youth unemployment. Apprenticeships can benefit young people and companies. Apprenticeships give young people professional experience, ensuring that when they finish their education they already have a foothold in the labour market. Employers also benefit from having a pool of available labour with the skills and experience that meets their demand for staff. Apprenticeships thus smooth the transition for young people from education into employment.

Dual learning systems

Because a skilled workforce matters for competitiveness, companies in some countries pay for a significant share of the costs of education, especially in vocational education and training. For example, in Germany, companies invest about €24 billion a year in their part of the dual training system. Dual learning apprenticeship systems see young people alternate between learning in schools and learning in companies. In many countries, however, apprenticeships are not considered an attractive option for companies or young people and the image of apprentices in some public perceptions is negative.

Research by BUSINESSEUROPE on apprenticeship systems across the EU, Creating opportunities for youth: how to improve the quality and image of apprenticeships, also shows the considerable diversity when it comes to the number of Member States operating dual systems and the form that such systems take.

Germany, Austria,S witzerland, Denmark and the Netherlands are examples of EU Member States with well established dual learning systems. These are also the countries with the lowest levels of youth unemployment inEurope. The Czech Republic, France, Hungary, Ireland, Poland and the UK have apprenticeship systems, but they are not as widespread as in the countries above. Cyprus, Greece, Italy are widening their approach towards apprenticeships, but it takes time and money to establish successful dual learning systems, including financial support from, and strong dialogue with, companies.

Cooperation is key

Greater synergies between the world of education and the world of business should be promoted at all levels – mismatches between skills supply and demand must be reduced.

Nevertheless, it is the responsibility of governments to ensure that pupils finish primary and secondary education with the adequate competences for further education. It is the role (and responsibility) of employers’ organisations to take part in the governance of dual learning apprenticeship systems and contribute to the design of curricula and their adaptation over time. This is an important factor to ensure their responsiveness to labour market needs and to avoid unnecessary red tape for companies. Employers’ organisations must also inform and motivate companies to become involved in the dual system, give them advice and organise cooperation between companies.

The EU is faced with a very severe economic situation and the effects of the crisis and ensuing recessions across Member States are impacting upon everybody in one way or another. The consequences for well educated young people are the prospect of months, if not years, of frustration and desperation if they are unable to make the transition from education to employment. This is why it is important that young people’s education includes practical professional experience so that a skills set can be added to the knowledge they acquire in the classroom.

Labour market needs should, therefore, be at the centre of education and apprenticeships should form a central pillar around which the EU and Member States orientate their responses to getting more young people into work.

This article is based on a presentation to the Institute for Public Policy Research at the event, Youth Unemployment in Europe: lessons for the UK, 12 July 2012.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Apprenticeships are brilliant, but a problem of this size needs a solution that can scale. There aren’t enough apprenticeship opportunities to absorb the need. Collaborative research projects are a way of bringing industry and students together whilst they are at college or university and are demonstrated to enhance the impact of the work being done, the learning and the student’s readiness for the workplace. Employers that engage with students early in their careers are also shown to do better at graduate recruitment. Let’s look at how we can incorporate more opportunities for industry sponsored research projects into business and higher education.