How have different European countries implemented austerity measures since the financial crisis? Andrea Müller, Irene Ramos-Vielba, Werner Schmidt, Annette Thörnquist and Christer Thörnqvist write on developments within four countries: Germany, Spain, Sweden and the UK. They argue that there is little evidence to suggest that the failure to modernise the public sector in these countries was a key driver in the economic problems caused by the crisis.

How have different European countries implemented austerity measures since the financial crisis? Andrea Müller, Irene Ramos-Vielba, Werner Schmidt, Annette Thörnquist and Christer Thörnqvist write on developments within four countries: Germany, Spain, Sweden and the UK. They argue that there is little evidence to suggest that the failure to modernise the public sector in these countries was a key driver in the economic problems caused by the crisis.

When we closely examine the national differences in public sector developments across four European countries (Germany, Spain, Sweden and the UK) in the context of the recent economic and financial crisis, we find that in Spain and the UK, austerity measures are now crucial in terms of cuts in public expenditure and deterioration of pay and conditions for public sector employees. However, besides these similarities, neither the reasons nor the consequences are the same. In Spain, and in some other countries of the Eurozone, austerity measures seem to result from the pressures of a new European governance regime related to the euro, while in the UK these policies appear self-imposed by the UK government, not least to restore confidence at the financial markets.

Austerity and the public sector in Germany, Spain, Sweden and the UK

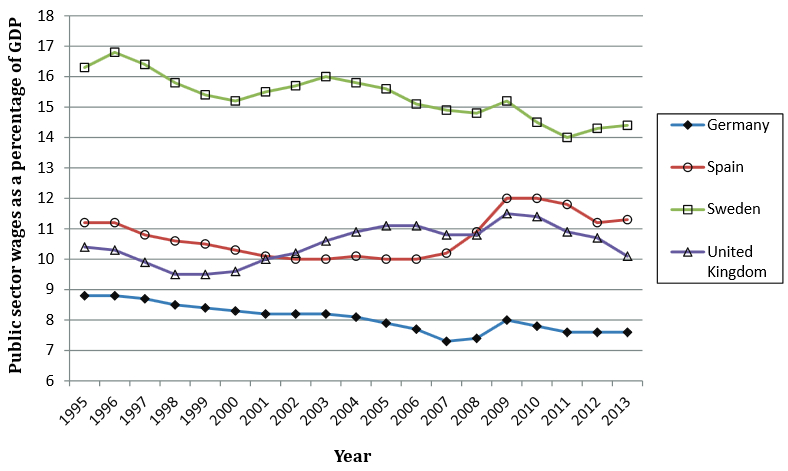

Sweden and Germany had already begun to implement austerity measures in the 1990s and policies of retrenchment continue to be pursued. However, there is no intensification as a consequence of the crisis. The assumption of a clear relationship between a large public sector and austerity and cutbacks as a consequence of the crisis cannot be proven. The smallest public sectors of the four countries are in Germany and in Spain, and the biggest is in Sweden, but a similar long-term evolution takes place regardless the size of the public sector or the hit of the financial and economic crisis.

The question arises whether such widespread austerity measures and wage cuts are simply a consequence of the public sector itself. Are they considered the penalty for failing to modernise and adjust the public sector in the past? In fact, there is no reason to blame the public sector for any of the economic problems which have emerged during the crisis and these problems are certainly not caused by wasted tax revenues in the public sector. Sovereign debt increased instead due to the financial and real estate crisis and bank bailouts.

Are austerity measures then merely ideologically driven? On one side, the answer to this is yes, since deregulation, privatisation, and adjustment to the private sector all follow the objective of a ‘lean state’. But this is a strategy which has strongly contributed toward delivering new fields of financial accumulation for capital in search of investment. Thus, while ideology does play a role, privatisation and cuts in public services are offering new areas for generating profits. Austerity is, therefore, not only a fallacy but also a clear expression of private interests.

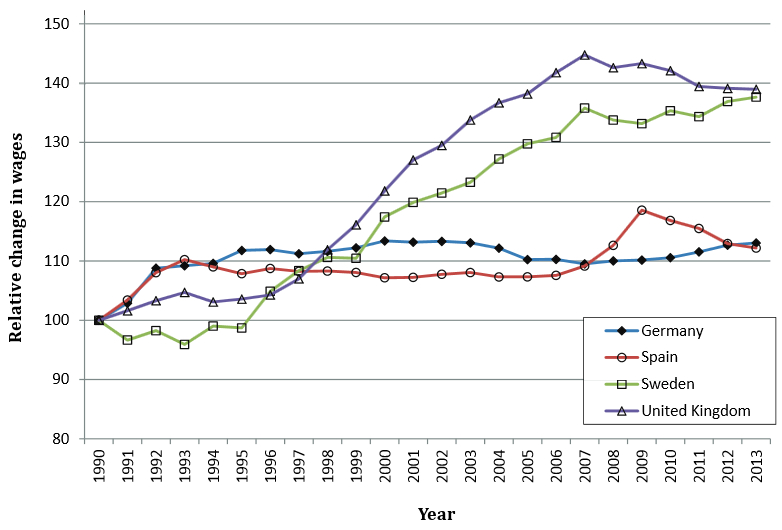

Public sector labour relations also differ between the four countries considered, both before and after the crisis, but are still more similar than compared to the industrial relations in the private sector. For instance, in the UK both union density and collective bargaining coverage are higher in the public sector than in the private one and the difference between the two sectors within the UK seems to be more pronounced than between the UK and Sweden as a whole. In Germany, the coverage rate is also higher than the average in the private sector, and civil servants (which are classed as public sector employees) are working under a completely different regime of unilateral determination of pay and conditions. Only in Sweden are private and public sector labour relations not subject to large differences. Chart 1 shows the development of wages in the overall economy in the four countries since 1990.

Chart 1: Real compensation per employee (1990-2013)

Note: The chart shows the change in wages for employees in Germany, Spain, Sweden and the UK. A figure of 100 indicates the real level of wages in 1990, while figures above and below 100 show relative increases/decreases to the 1990 level in real terms. Figures are from Eurostat and Ameco. See the authors’ longer paper for more details.

When we observe the development of compensation of public sector employees in the years before and after the crisis, the resulting figure illustrates convergence. The higher increases which happened in Sweden, the UK and Spain in the past have decreased. In Germany, however, this situation is reversed: there was a decrease of real wages before the crisis, and an increase in the aftermath. This means convergence in outputs, but there are serious doubts as to whether such developments will last. Moreover, similar changes imply maintenance of profound differences in substance. Chart 2 shows the change in the share of wages for public sector employees as a percentage of GDP.

Chart 2: Compensation of public sector employees as a percentage of GDP (1995-2013)

Note: Figures are from Eurostat. See the authors’ longer paper for more details.

Depending on the criteria and the timeframe we are looking at, we can detect similarities or differences. In particular in the context of the crisis, there have been remarkable curtailments of public sector labour relations, both in Spain and to some extent also in the UK. Meanwhile, changes in Sweden (still confronted with privatisation implemented by the former centre-right government) and Germany (where the Social Democrats have been part of a grand coalition since 2013) cannot be attributed to the recent crisis. However, neither is it clear whether these changes will result in more similarities or divergences, nor whether these developments will persist. Under such circumstances, and given the drastic negative social impact generated, resistance to austerity could mean a starting point for trade unions to forge a broader social alliance to turn the tide, but evidence of this occurring is still inconclusive.

Scapegoating the public sector in Europe?

According to our findings, at a first glance the crisis is fostering divergent development of the public sectors in the countries considered, however, looking at a longer period, some similarities appear: privatisation, austerity measures and downsizing, as well as harder working conditions for public sector staff and the weakening of labour relations, are common features in all four countries. The difference seems to be more in the date of occurrence rather than in the development itself.

Nevertheless, there is no apparent nexus between public sector developments and either the institutional path dependence or the type of market coordination. Neither national differences nor a view of the full empirical diversity alone seem sufficient to explain some key economic and societal developments underpinning the public sector cutbacks. We assume that, despite all differences between and within countries, there is a common background: the crisis of the post-war constellation in Europe and the ‘Fordist regime’ of accumulation, which is still not over and has led to a pronounced increase in inequality.

However, if the public sector crisis is caused by inequality and a dysfunctional regime of financialised accumulation, then austerity, wage cuts, and public sector retrenchment are clearly the wrong measures to take. These measures accelerate inequality, which it is at the heart of disproportional economic development. Fuelling a vicious circle, cuts in public expenditure will likely produce more economic inequalities, more indebtedness, further bubbles, further financial crises and additional sovereign debt. Are public sector adjustments subsequently to be expected again as a consequence?

Note: The English version of this article was originally published on our sister site, the LSE’s EUROPP blog, and gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before commenting. Featured image credit: Images Money (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Andrea Müller – University of Tübingen

Andrea Müller – University of Tübingen

Andrea Müller is a member of research staff at the FATK institute at the University of Tübingen.

–

Irene Ramos-Vielba – University of Tübingen

Irene Ramos-Vielba – University of Tübingen

Irene Ramos-Vielba is a member of research staff at the FATK institute at the University of Tübingen.

–

Werner Schmidt – University of Tübingen

Werner Schmidt – University of Tübingen

Werner Schmidt is Managing Director of the FATK institute at the University of Tübingen.

–

Annette Thörnquist – Linköping University

Annette Thörnquist – Linköping University

Annette Thörnquist is Associate Professor at Linköping University and is currently working on the “Crisis, State and Labour Relations: Austerity Policy and Labour Relations of the Public Services” project at the FATK institute at the University of Tübingen.

Christer Thörnquist – University of Tübingen

Christer Thörnquist is working on the “Crisis, State and Labour Relations: Austerity Policy and Labour Relations of the Public Services” project at the FATK institute at the University of Tübingen.

To paraphrase or wells animal farm the governments believe private good public bad although it inevitably means paying more for a reduced service.