According to polling by Ipsos-MORI, immigration has topped the economy to become the most important issue for British people. Empirical research on the labour market effects, however, finds little overall adverse impact of immigration. Jonathan Wadsworth examines the evidence.

According to polling by Ipsos-MORI, immigration has topped the economy to become the most important issue for British people. Empirical research on the labour market effects, however, finds little overall adverse impact of immigration. Jonathan Wadsworth examines the evidence.

Immigration is a big issue. Twenty years of rising immigration mean that there are now around 7.8 million individuals (and 6.5 million adults of working age) living in the UK who were born abroad. This is a large, but not unprecedented, rise in the UK population. Between 1975 and 1990, the UK working age population grew by around 200,000 a year, on average. This was driven not by immigration, but by a rise in the UK-born population. Between 1995 and 2014, the working age population also grew by around 200,000 a year, but the majority of this growth was due to immigration. Table 1 shows that 16.6 per cent of the UK working age population are now immigrants, double the share in 1995.

Table 1: Immigrants in the UK’s working age population (16-64)

| Total (millions) | UK-born (millions) | Immigrant (millions) | Immigrant share (percentage) | |

| 1975 | 33.6 | 31.2 | 2.5 | 7.3% |

| 1990 | 36.4 | 33.7 | 2.7 | 7.5% |

| 1995 | 36.4 | 33.4 | 3.0 | 8.2% |

| 2014 | 40.6 | 33.9 | 6.7 | 16.6% |

Source: Labour Force Survey (LFS)

Since immigration increases labour supply, it may be expected to reduce wages of the UK born. UK immigrants are relatively skilled (versus, for example, those in the United States), so such pressure is relatively more likely to reduce inequality as the wages of top jobs are likely to fall. But if labour demand rises, there may be no effects of immigration on wages and employment. An open economy may also adjust by means other than wages, such as changing the mix of goods and services produced.

If there is excess demand for labour in the receiving country, the impact of immigration will be different from that in a country already at full employment. Concerns about substitution and displacement of the UK-born workforce become more prevalent when output is demand constrained, as in a recession or when capital is less mobile.

Empirical research on the labour market effects of immigration to the UK finds little overall adverse impact on wages and employment for the UK-born. The empirical evidence shows that:

- Immigrants and native-born workers are not close substitutes on average (existing migrants are closer substitutes for new migrants). This means that UK-born workers are, on average, cushioned from rises in supply caused by immigration.

- The less skilled are closer substitutes for immigrants than the more highly skilled. So any pressures from increased competition for jobs is more likely to be found among less skilled workers. But these effects are small.

- There is no evidence that EU migrants affect the labour market performance of native-born workers.

One concern with these findings is that they were based on data preceding the recession when demand was higher on average. To look at this more directly in recent years, we can examine whether immigration is associated with joblessness of the UK-born population across different geographical areas. If rising immigration crowds out the job prospects of UK-born workers, we might expect to see joblessness rise most in areas where immigration has risen most.

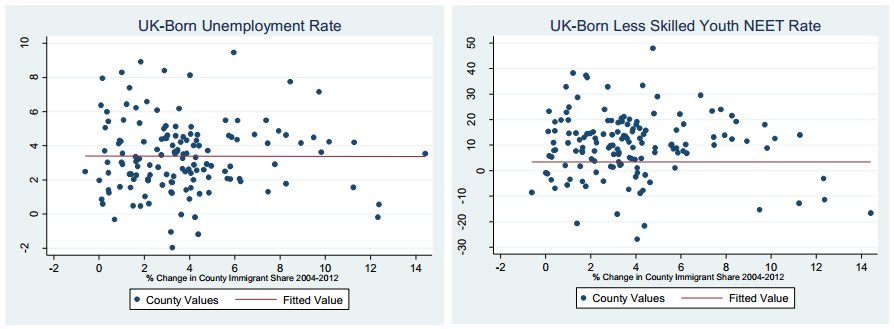

Figure 1 plots the change in each county’s unemployment rate for UK-born workers against the change in its immigration share between 2004 and 2012. Each dot represents a county. The red line summarises the strength or otherwise of the relationship. The flatter the red line, the weaker any correlation.

Figure 1: No relationship between changes in immigration and unemployment, 2014-2012

Source: Annual Population Survey

The figure shows the lack of correlation between changes in the native-born unemployment rate and changes in immigration. While there appear to be no average effects, it may be that the average is concealing effects in the low wage labour market where (despite their higher relative education levels) many new immigrants tend to find work. Equally, there may also be a positive effect on wages in the high wage labour markets where it may take more time for the skills that immigrants bring to transfer.

But Figure 1 shows that there is no evidence of any association between changes in the less skilled (defined as those who left school at age 16) native youth NEET (‘not in education, employment or training’) rate and changes in the share of immigrants. Counties that experienced the largest rises in immigrants experienced neither larger nor smaller rises in native-born unemployment.

Figure 2 repeats the exercise for wages. Again, there is little evidence of a strong correlation between changes in wages of the UK-born (either all or just the less skilled) and changes in local area immigrant share over this period.

Figure 2: No relationship between changes in immigration and local wages, 2004-2012

Source: Annual Population Survey

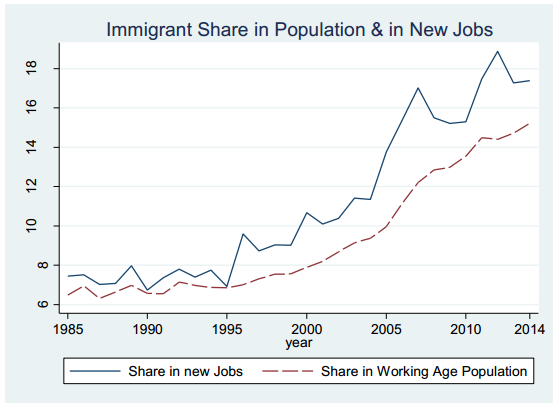

Immigrants and new jobs

It is sometimes said that immigrants account for the majority of the new jobs generated. This is a misinterpretation of changes in aggregate jobs data. In times when the population is rising, the number of immigrants will grow alongside the numbers in employment. To look at who gets new jobs, we need to look at evidence on hiring. The actual immigrant share in new jobs (the share of immigrants in jobs that have lasted less than three months) is broadly the same as the share of immigrants in the working age population (see Figure 3). Therefore it is not the case that most new jobs are taken by immigrants.

Figure 3: Immigrant share in new jobs

Source: LFS

Immigrants and other economic outcomes – public finances and public services

In terms of public finances, because immigrants are on average younger and in work, they tend to demand and use fewer public services and they are more likely to contribute tax revenue (Dustmann and Frattini, 2014). This is particularly true with EU immigrants and also with recent arrivals from outside the EU.

The labour market is just one area in which rising immigration could have important effects, though there are many others, such as health, schools, housing and crime. We know much less about these issues than we do about the labour market, but there is a growing body of UK research evidence on these important issues.

On balance, the evidence on the UK labour market suggests that fears about adverse consequences of rising immigration regularly seen in opinion polls have not, on average, materialised. It is hard to find evidence of much displacement of UK workers or lower wages. Immigrants, especially in recent years, tend to be younger and better educated than the UK born and less likely to be unemployed. So perceptions do not seem to line up with the existing evidence and it is perhaps here that we need to understand more.

The longer version of this article, “Immigration and the Labour market” by Jonathan Wadsworth, is part of the CEP’s series of briefings on the policy issues in the May 2015 General Election.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting. Featured image credit: Nicola Romagna CC BY 2.0

Jonathan Wadsworth is Professor of economics at Royal Holloway and a Senior Research Fellow in CEP’s labour markets programme.

Jonathan Wadsworth is Professor of economics at Royal Holloway and a Senior Research Fellow in CEP’s labour markets programme.