England is an outlier among OECD countries in having both lower numeracy and literacy levels among school pupils aged 16 to 20 than among those in their 60s. Gwyn Bevan argues this constitutes yet another example of serious dysfunctions in the governance of England’s public services.

When the Coalition Government was “fixing the roof” from 2010 to 2015, it was doing so figuratively, but not literally. It cut the planned school building programme. In 2018, a school roof built with planks using Reinforced Autoclaved Aerated Concrete (RAAC) collapsed. In 2019, a Report from the Institute of Structural Engineers highlighted the need to replace all such planks in flat roofs in schools. In the four years that followed there have been seven Secretaries of State for Education. The current incumbent was the fifth appointed in 2022. In September 2023, her department asked headmasters of over 100 affected schools to find alternative accommodation days before the start of the school term. Why do we have a government that was able repeatedly to organise piss-ups in 10 Downing Street in the midst of a country-wide severe lockdown, but struggles effectively to govern our public services? My forthcoming book, How Did Britain Come to This?, aims to explain.

A missing link

“Fixing the roof” has been a recurrent problem for Glyn Potts, headmaster of Oldham’s Newman Roman Catholic College since his school was built under the last Labour government’s Private Finance Initiative. Oldham had 365 mills, because its moist atmosphere meant the spinning cotton threads were less liable to break. Its persistent drizzle now means ten or more classrooms are frequently flooded at Potts’ school. Jennifer Williams in the Financial Times vividly describes the many obstacles he faces in educating his pupils: their poverty and hunger (43 per cent are eligible for free school meals); threats of homelessness; the sequelae of COVID-19 (mental health problems, neglect, persistent truancy, harmful social media use); replacing teachers who are leaving (with few or no applicants). Now we seem to have headmasters struggling with problems from outside the classroom with little support from the Department of Education in Whitehall, whose staff live and work in another world. So why have governments developed such a system?

A good friend of mine remembers, when he was a headmaster in Oxfordshire, if he had a problem, he knew he could always see Tim Brighouse, its Chief Education Officer (at 7 o’clock in the morning). But, local education authorities that were supportive and close to schools found it hard to challenge to the “secret garden” of teachers’ professional autonomy. John Davis describes the flagrant failure of the policy of the Inner London Education Authority, which was “you appoint a good headteacher, and then he [sic] runs the show”. Education at its William Tyndale junior school consisted of playing in the classroom or the playground so lessons hardly existed. As one of its unfortunate pupils so eloquently put it “You don’t get learned nothing at this school”.

Market failure

The “secret garden” was opened up with three sets of radical reforms from 1988. First, changing from the hierarchy of local educational authorities to a market, which aimed to offer parents a choice between competing schools with funding following the pupil. Second, publication of the rankings of schools’ performance in league tables of examination results. Third, replacing an occasional visit by the collegial Her Majesty’s Inspectors of Schools (HMIs) with the “reign of terror” by the Office for Standards in Education (OFSTED), and publication of their inspections. Christopher Hood et al argued that the substantial “relational distance” between OFSTED and schools was vital for them in challenging the “secret garden”. Although they also found that only 67 of the 3,600 secondary school OFSTED inspected from 1993 to 1997 were deemed to be “failing”.

The funding constraint that aims to match total supply of schools to total demand compromises the effectiveness of the market

An IFS report explained why the funding constraint that aims to match total supply of schools to total demand compromises the effectiveness of the market: good schools are oversubscribed and poorly performing schools do not exit the market. The former use their catchment areas as the principal criterion in selecting pupils and thus their educational benefits are capitalised in the housing market. So, what has been the educational impact of these reforms?

How to reverse the trend?

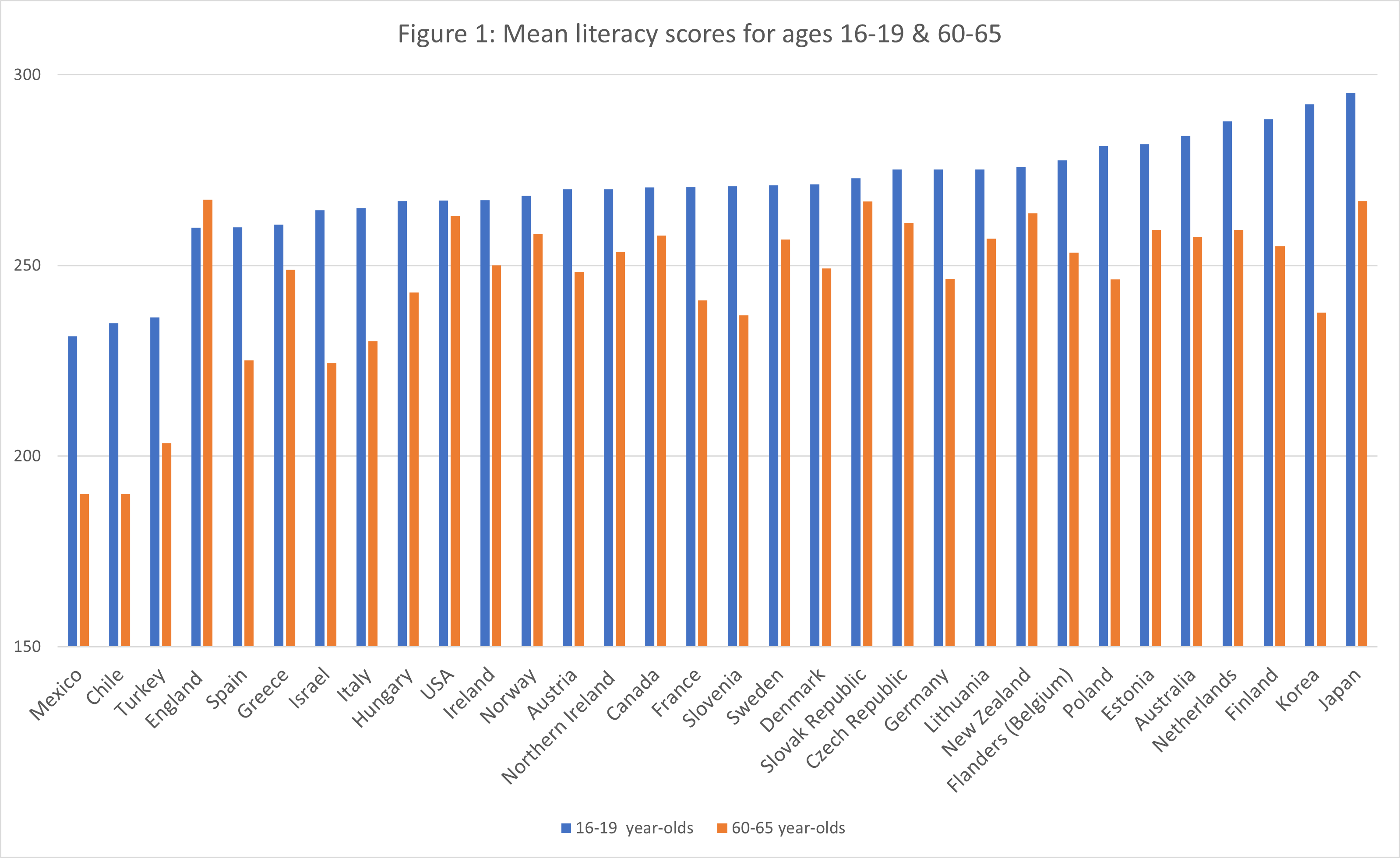

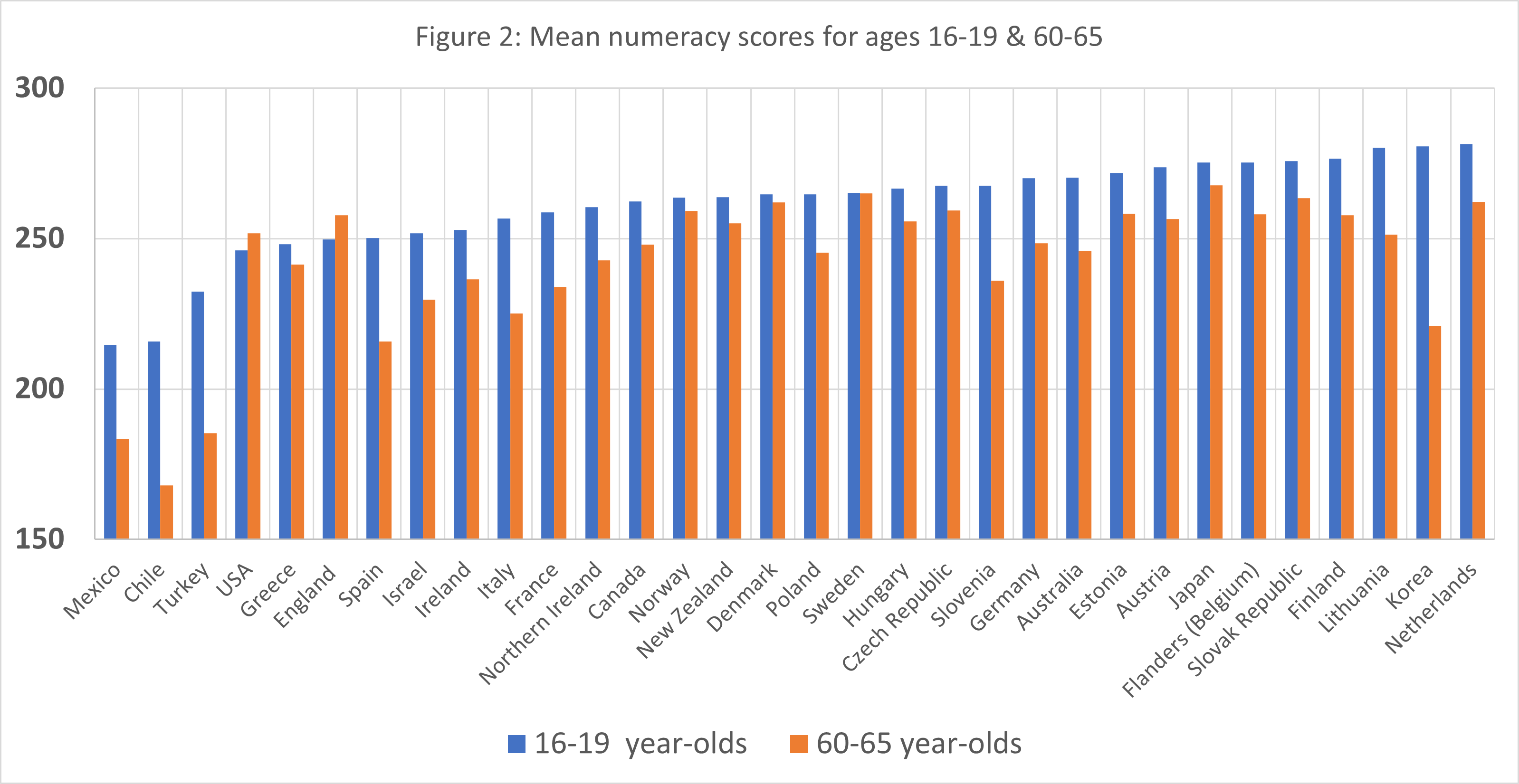

An OECD study, published in 2019, gave estimates of literacy and numeracy skills across age groups from 16 to 65, for 32 countries. (The data are from two surveys: for most countries, including England, over 2011 and 2012, and others over 2014 and 2015.) Figures 1 and 2 below compare the results for the youngest (16 to 19) and oldest (60 to 65) groups and show that for virtually all OECD countries, the younger group substantially outperformed the older. England was ranked 29th for literacy and 27th for numeracy for the youngest group, and is the only country in which the older group, who would have been educated in the “secret garden” of the 1960s, have higher scores than the younger for both literacy and numeracy skills.

Although we would expect the market for schools to work best in cities, it failed in London. That is why the Blair government launched the London Challenge, which ran from 2003 to 2011. Marc Kidson and Emma Norris describe how that combined “experimentation on the ground, [and] rapid feedback and learning by advisers and officials, with strong project management across different strands of the policy”. It improved the performance of secondary schools in inner London local authorities from being “the worst performing to the best performing nationally”. So, if England wants to improve in its ranking of the youngest age group in the next OECD surveys of literacy and numeracy skills, perhaps we need local organisations throughout England that could replicate the London Challenge? And perhaps these local organisations could support our headteachers, so they could go back to focusing on the education of our children rather than on fixing roofs.

You can listen to Gwyn Bevan discussing this and other themes tackled in his book at the upcoming LSE event How did Britain come to this? The accidental logics of Britain’s neoliberal settlement.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: Vanessa Garcia via Pexels.