Jonathan Wheatley explains the shifting positions of voters on economic matters and matters of culture. He writes that between 2015 and 2017 support for Britain’s main parties became much more predicated on issues of culture and identity, reflecting a radical change in how parties attract voters. This shift may lead to a restructuring of the UK party system and the end of traditional party allegiances.

Jonathan Wheatley explains the shifting positions of voters on economic matters and matters of culture. He writes that between 2015 and 2017 support for Britain’s main parties became much more predicated on issues of culture and identity, reflecting a radical change in how parties attract voters. This shift may lead to a restructuring of the UK party system and the end of traditional party allegiances.

The general election of 2017 was remarkable for a number of reasons, but one particularly noteworthy development was the apparent return to two-party politics. Combined, the Conservatives and Labour captured 82.4% of the vote, the highest proportion won by these two parties since 1970, and a huge leap up from the two previous elections of 2010 and 2015 when they garnered just 65.1% and 67.3% (respectively) between them.

So, to coincide with the 2016 vote to leave the European Union, did this mark a return to the sort of politics that Britain experienced before the country joined the Common Market in 1973? Is the country once again experiencing the kind of left-right schism that we saw during the first 25 years after World War II with a choice for voters between a left-wing Labour Party and a right-wing Conservative Party and very little else?

My own recent analysis, published in Palgrave Pivot format, suggests that politics in Britain today is far less predicated on the left-right divide than previously – at least in the classic sense of a struggle between the interests of labour and capital. In my research I identify latent ideological dimensions from opinion data taken from successive waves of the British Election Study (BES) during 2015-2017, and from corresponding data from users of a Voting Advice Application called WhoGetsMyVoteUK. Following on from my earlier work, I show that political competition in Britain is defined by two underlying dimensions: one economic dimension, which corresponds to the economic notion of left versus right, and one cultural dimension. This cultural dimension incorporates a range of social issues such as equal opportunities for minorities and the desirability (or not) of the death penalty, as well as a number of issues closely related to globalisation, such as immigration, foreign aid and European integration. This dimension, sometimes referred to as “open” versus “closed”, pits patriotic, Eurosceptic social conservatives against cosmopolitan liberals and by 2017 seemed to be stronger and more coherent in terms of ordering voters’ political orientations than the economic dimension. This suggests that the economic conflict between capital and labour that defined political competition in the 20th century is giving way to a new sort of conflict based on culture and identity.

Using multivariate regression analysis on BES data I also found that a voter’s position on this cultural dimension is determined more by social background and status than their position on the economic dimension, suggesting that this conflict is rooted in social structure. Age, education, and proximity to the global hub that is London appear to be very strong determinants of the former, while only income has an equivalent effect on the latter. This gives credence to the view of scholars such as Hanspeter Kriesi and others that both in Britain and in the rest of Europe politics is increasingly structured by a divide between “winners” and “losers” of globalisation and this has led to issues of cultural and national identity becoming more salient politically.

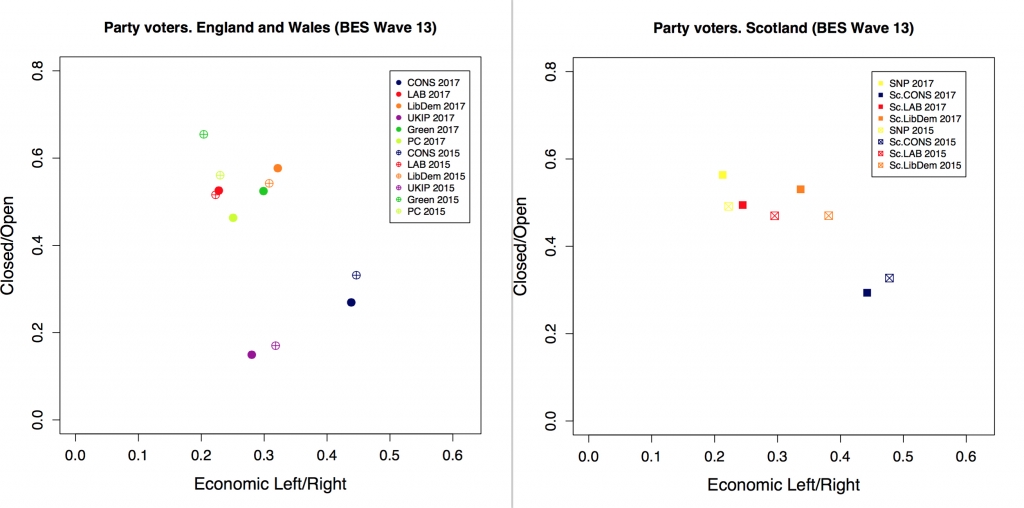

Another key finding of this research is that between the general elections of 2015 and 2017 Labour and SNP voters, on the one hand, and Conservative voters, on the other, became more polarised with respect to one another along the cultural dimension (see the diagrams above). However, this was almost entirely due to a shift amongst Conservative voters towards the “closed” pole of this dimension and (in Scotland) a similar shift by the SNP towards the “open” pole (Green and UKIP voters are not included in the Scotland map due to insufficient observations). Paradoxically, despite the emergence of Jeremy Corbyn as Labour’s leader and growing opposition to capitalism within the Labour Party, there does not seem to be any more overall polarisation between the voters of the main political parties on the economic dimension. Outside Scotland even the average Labour voter barely shifted leftward in the economic sense between 2015 and 2017.

The Brexit referendum was most likely the catalyst for a strategic re-positioning by the Conservative Party. By championing a “red, white and blue” Brexit and by dismissing “citizens of the world” as “citizens of nowhere”, Theresa May moved the Tories towards the “closed” end of the political spectrum, occupying much of the territory that UKIP had occupied in 2017. The appeal was partly successful insofar as the Tories tended to gain votes in constituencies in which the Leave vote exceeded 63%, even if they lost the votes of “open” Remainers who had voted for the party in 2015. Labour meanwhile sought to reframe the debate away from “open”/”closed” issues such as Brexit, giving centre stage to economic issues, framing the struggle as one between “the many” and “the few”. Even though they had limited success in this respect, they managed to win over many young, well-educated, middle class Remainers at the “open” end of the spectrum.

Overall these trends continued after the election, but the tensions inherent in both parties threatened to render both asunder. For the Tories, the impending reality of Brexit led to an apparently irreconcilable split between the “open” and “closed” wings of the party that is reflected in the increasingly bitter dispute over whether the UK should make a clean break with the EU or remain close to the EU orbit. For Labour the dilemma is whether to build further the party’s support base amongst “open”, young well-educated voters by opposing Brexit, or whether instead to take a “centrist” position on the cultural dimension, maintain a position of “constructive ambiguity” on Brexit and continue to try to shift the narrative from “open” versus “closed” to “the many” versus the “few”. This way it is hoped the party could appeal to Brexit-backing voters in the post-industrial heartlands, including some who defected to the Tories in 2017. It is the latter position that the Labour leadership is pursuing.

In terms of framing the narrative, perhaps Labour could take a leaf out of the SNP’s book. Drawing from BES data I find that in Scotland the correlation between voters’ orientations on the (left-right) issue of redistribution and their attitudes to Scottish independence was much greater in 2017 than it had been six months before the independence referendum in 2014. This is because the SNP successfully “framed” the issue of independence as one about freedom from London-imposed economic austerity and inequality. If Labour could similarly frame Brexit as “project about neoliberal deregulation… Thatcherism on steroids”, as David Lammy suggests, it may be possible to reconcile the two competing Labour narratives, but it would require the kind of deft leadership that the SNP showed during and after the independence referendum. For the Tories the task of holding together is likely to be even more complicated as the gap between “open” pro-European Tories and the hardline Eurosceptics of the European Reform Group seems unbridgeable.

There is a therefore a very real possibility that the shift from left-right politics to open-closed politics may lead to a complete restructuring of the party system and the end of traditional party allegiances. The political map of 2020 may look very different from that of 1970.

________________

Note: the above draws on the author’s latest book, “The Changing Shape of Politics: Rethinking Left and Right in a New Britain” (Palgrave, 2019).

Jonathan Wheatley is Senior Lecturer in Comparative Politics at Oxford Brookes University.

Jonathan Wheatley is Senior Lecturer in Comparative Politics at Oxford Brookes University.

Those who are ‘closed’ are not so much patriotic as nationalists. I ‘tend’ to accept Orwell’s view that patriotism is defensive & cultural while nationalism is aggressive & militarily aggressive. I put ‘tend’ as we know that even this is nuanced so the SNP has been in my opinion tended to be anti English under Salmond, but much less so under Sturgeon.How long can the present U.K. Government & Opposition use the term ‘nation’ for GB if Labour & U.K. again tendencies while both using the term ‘our four nations.’ This paradox is now a contradiction. Conservatives have managed to square the circle of being the party of the Union while being in practice the party of England by giving much money to Scotland & Northern Ireland while Labour is still the party, it seems the only party for Unionism in the sense of trade unionism when this is in decline; both Thatcher & Lawson aim of three being being more individual shareholders than trade unionists has so far not occurred. Ironically. Corbyn has pointed a way out of the rise of the self employed as has Starmer in pointing out their importance economically & politically; Thatcher’s children, before that the supporters of the Liberal party. Of as many Brexiters wish for the return to the Fifties, a heyday of trade unionism.

Another aspect of culture is what is meant by it. A tradesman night despise ‘artyfarty’ culture yet in their spare time practise karate or T’ai Chi etc. yet these are not part of our culture being Asian – yet they are now, due to their popularity? It is ‘high culture’ they dislike such as the ‘foreign’ Beethoven’s 9th Symphony- the European anthem when really part of World culture – my bias – ironic that Beethoven was a friend of Goethe, who later along with Verdi – increased the respect for Shakespeare on the Continent.

There is a ‘tendency ‘ to see all Brexiters as ‘closed’ yet during the 1975 referendum the chairman of the Leave campaign was a free trade member of the Liberal party who saw the EC as ‘’a rich man’s club; he like Gaitskell was pro Commonwealth & not just the old Dominions.

What an i interesting blog.

Thank you,

Peter

This open/closed dichotomy has been known for over a decade. It may have been hidden during the Blair years,but it was certainly there then.

https://www.flourish.org/2016/07/on-finding-political-axes-using-maths/

Chris Lightfoot’s and Tom Steinberg’s work with YouGov back in 2005, which is shown in the slides in the posting above, is described in Chris’ blog which is still available through the Wayback Machine.

https://web.archive.org/web/20060219025424/http://ex-parrot.com/~chris/wwwitter/20050415-my_country_right_or_left.html

So which one is “open” and which one is “closed”? Is the “closed” one the one that wants to engage with the whole of the world, and open up limited immigration to everyone on the same basis, and the “open” one the one which favours a closed Eurocentric state? Have I got that the right way round?