British and English national identities have long been considered to have porous boundaries whereby English individuals consider the terms more or less interchangeable. Using panel data, John Kenny, Anthony Heath, and Lindsay Richards demonstrate that there is a notable degree of fluidity between identifying as British or English. This is higher than the fluidity between other national identities in the UK as well as more fluid than moving between any partisan or EU referendum identities.

British and English national identities have long been considered to have porous boundaries whereby English individuals consider the terms more or less interchangeable. Using panel data, John Kenny, Anthony Heath, and Lindsay Richards demonstrate that there is a notable degree of fluidity between identifying as British or English. This is higher than the fluidity between other national identities in the UK as well as more fluid than moving between any partisan or EU referendum identities.

There is, by now, plenty of evidence of feelings of exclusive Englishness being mobilised in the Brexit referendum result, whereby 74% of those who felt ‘English but not British’ voted to leave, whereas the figure for those who felt ‘British but not English’ was just 38%. However, at the same time, British and English national identities have historically been considered to have fuzzy frontiers, with the terms often used interchangeably by English people. So, how can we reconcile the idea that British and English identities are interchangeable, with the idea that our national identity influences our politics? To what extent do people chop and change between identities and what might the political consequences be?

Until now, examining whether individuals display consistency in their national identities within the UK has proven difficult due to data limitations. When panel surveys – which repeatedly survey the same individuals – have asked about respondents’ preferred national identity, they have tended to only ask it in one wave of data collection under the implicit assumption that national identity does not change. This, therefore, has acted as a barrier to investigating whether movement between British and English preferred national identities are stable or fluid overtime.

As part of a project monitoring public opinion in the run up to Brexit that was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council’s ‘The UK in a Changing Europe’ initiative, we surveyed a UK-wide panel of individuals on eight occasions over the course of two years, beginning in July 2017 and ending in August 2019. To overcome the aforementioned data issues on capturing changes between having a British and an English preferred identity, and to see if the ‘fuzziness’ of the distinction between Englishness and Britishness holds, we fielded questions on national identity to each individual on every occasion. Firstly, respondents were asked, ‘Turning now to your national identity which, if any, of the following describes the way you think of yourself? Please choose as many or as few as apply’, with options of British, English, European, Irish, Northern Irish, Scottish, Ulster, Welsh plus ‘other’, ‘I don’t think of myself in this way’ and ‘I prefer not to say’ options. For those with more than one identity, this was followed up with the question ‘And if you had to choose, which one best describes the way you think of yourself?’.

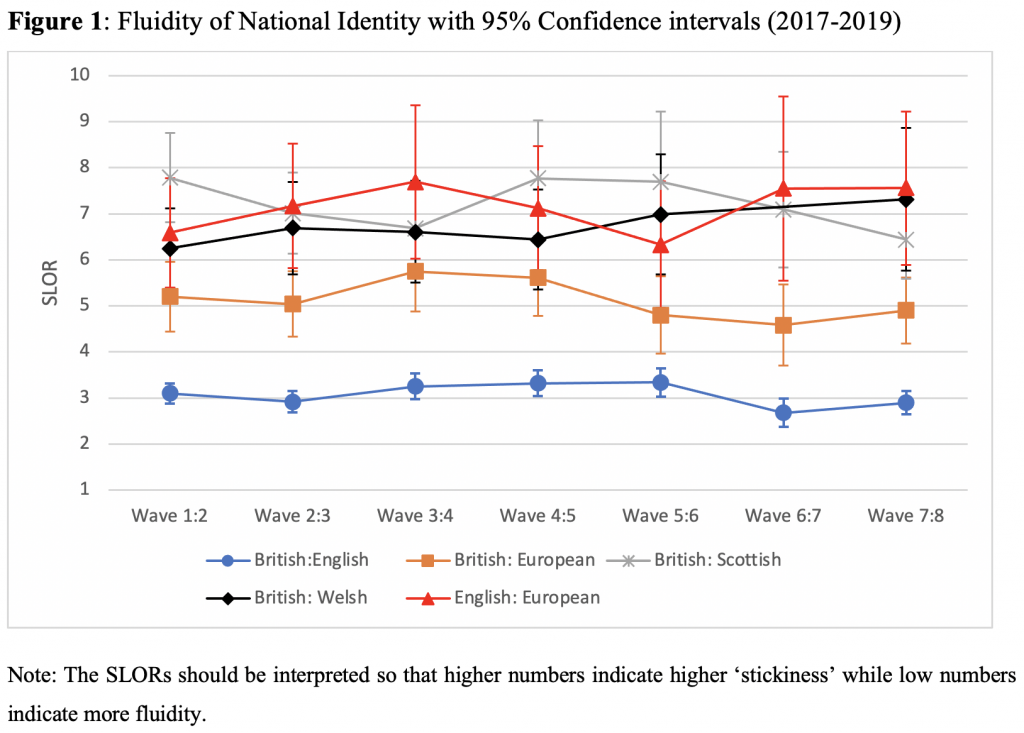

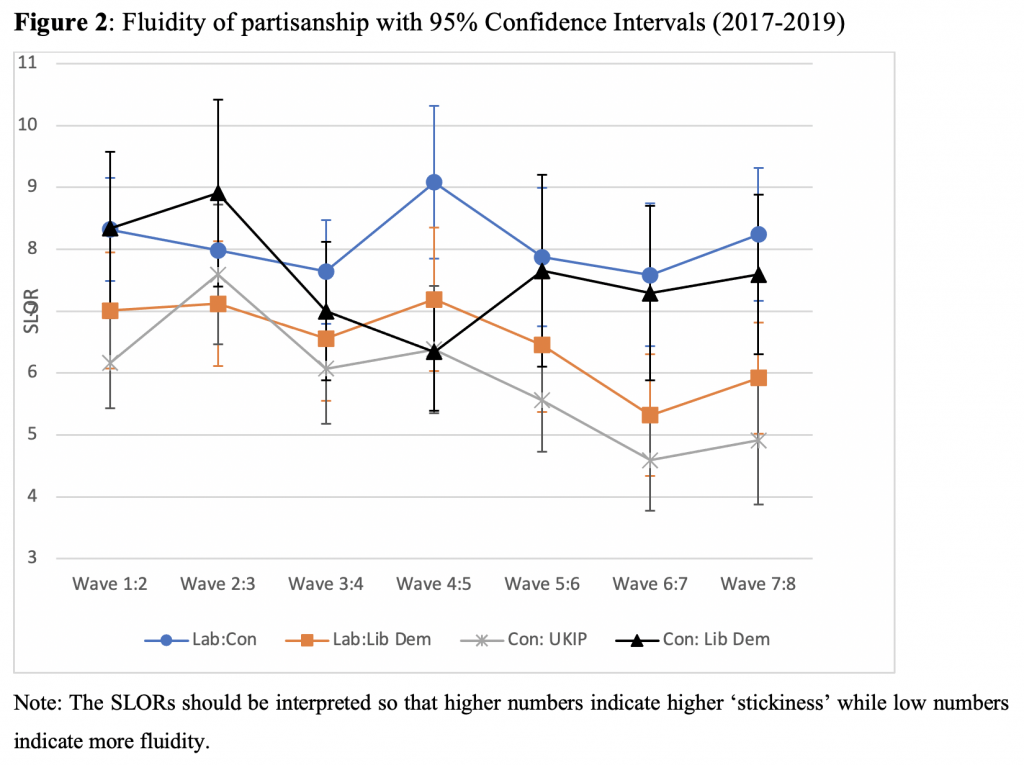

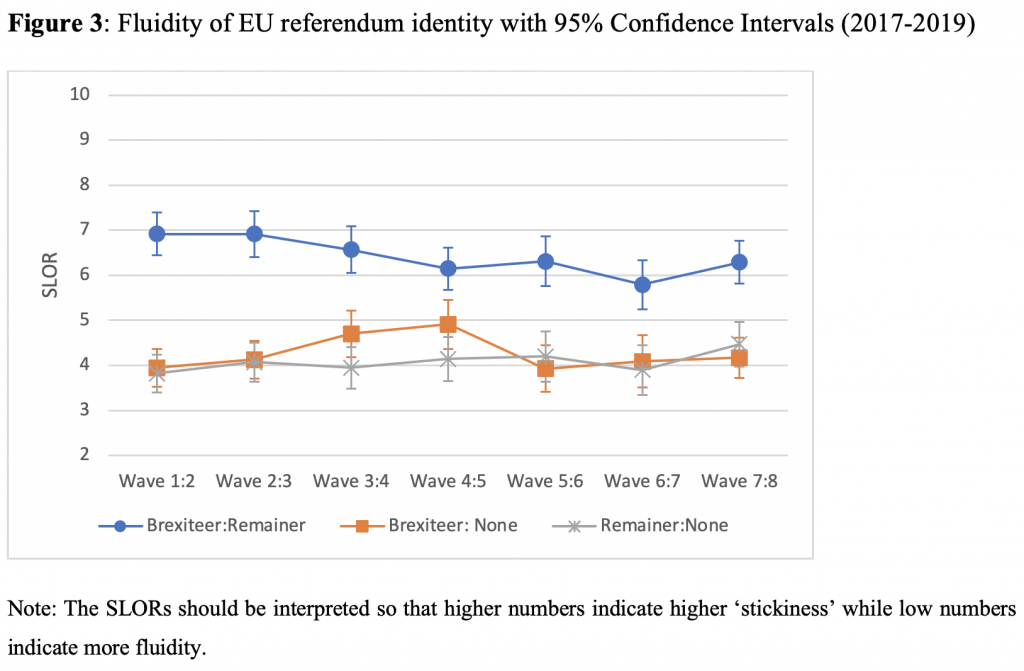

Using individuals’ preferred national identity, we examine the fluidity of national identities between waves – that is the statistical association between current and previous identity net of the swings between the different identities. This we measure through calculating symmetrical log odds ratios (SLORs). These ratios (technical explanation here) can be interpreted such that lower values approaching zero indicate greater fluidity whereas higher values indicate greater stickiness between the two given options.

Figure 1 displays our first set of results. We find relatively high levels of fluidity between British and English preferred identities, evidencing that English and British identities are more likely to change, within the same individual over time, than are British and Scottish or British and Welsh identities. To quantify this, between wave 1 and 2, 24% of respondents who had a primary English identity in wave 1 switched to a primary British identity in wave 2 with 75% maintaining their English identity, and the figure going in the opposite direction from British to English was 12% with 83% maintaining their Britishness. While the boundary is thus relatively fuzzy, it is not interchangeable within our measurement windows. Moreover, there is consistently higher fluidity between British and European preferred identities than between English and European preferred identities. This supports the view that feelings of Britishness are more compatible with feelings of Europeanness than are feelings of Englishness.

In addition, we explored the link between fluidity and Brexit preferences. We found that individuals with a preferred English identity who would vote Remain if another referendum were to be held are much more fluid in their Englishness in subsequent waves than those with an English identity who would vote leave. It suggests a kind of dissonance between having a preferred English identity and being on the Remain side of the referendum debate.

Finally, we compare the fluidity seen been British and English preferred identities to the benchmarks of the fluidity between partisan identities (Figure 2) as well as the newly emerged EU referendum identities (Figure 3). While we know from previous research that Remain and Leave identities are quite fixed, it is quite stark that even the partisan identities that display the greatest fluidity during this timeframe (for example Labour/Liberal Democrat or Conservative/UKIP) are much less fluid at all time points than the level of fluidity between British and English preferred identities. This underscores the relative fluidity of the boundary between British and English identities

Identity can provide a powerful lens through which individuals interpret events around them. Empirically demonstrating for the first time the fluidity of Britishness and Englishness is important as it suggests that – at least for the time being – the blurred boundaries between these two identities that have helped to enable England to be satisfied within the UK continue to hold some sway. Nonetheless, with substantial majorities holding onto their primary Englishness or Britishness over consecutive survey waves, such identities do still offer sufficient stickiness for the differences between them to continue to be considered politically relevant. While the lower stability in maintaining preferred English identity for those with a remain vote persuasion is notable, what is particularly striking is that none of our analysis points to a growing sense of English identity over the course of the Brexit negotiations. Our findings thus may provide something of a corrective to recent strong claims about the emergence of English national identity from the shadows of British identity. A process of gradual evolution of English identity is probably under way, but there is still a long way to go before Englishness becomes as distinct an identity as the Scottish or Welsh ones are.

____________________

Note: The above draws on the authors’ published work in Political Studies.

John Kenny is a senior research associate at the University of East Anglia.

John Kenny is a senior research associate at the University of East Anglia.

Anthony Heath, CBE, FBA, is a senior research fellow at the Centre for Social Investigation, Nuffield College, University of Oxford.

Anthony Heath, CBE, FBA, is a senior research fellow at the Centre for Social Investigation, Nuffield College, University of Oxford.

Lindsay Richards is a lecturer in the Department of Sociology, University of Oxford and an associate member of the Centre for Social Investigation at Nuffield College.

Lindsay Richards is a lecturer in the Department of Sociology, University of Oxford and an associate member of the Centre for Social Investigation at Nuffield College.

Photo by Pawel Czerwinski on Unsplash.