While there has been improvement over the last couple of decades, there remains large ‘gender gaps’ in employment and wages. Ghazala Azmat explores the evidence on the key drivers of gender gaps and the effectiveness of ‘family-friendly’ policies to address them, highlighting the policy proposals of the main political parties in this election.

While there has been improvement over the last couple of decades, there remains large ‘gender gaps’ in employment and wages. Ghazala Azmat explores the evidence on the key drivers of gender gaps and the effectiveness of ‘family-friendly’ policies to address them, highlighting the policy proposals of the main political parties in this election.

Differences in the labour market experiences of men and women have fallen over the last 20 years, but there are still sizeable ‘gender gaps’ in employment and wages. Gender gaps in wages and employment tend to be most pronounced among women with young children. To try to address this, the main political parties have promised improvements in the provision of childcare in their election campaigns.

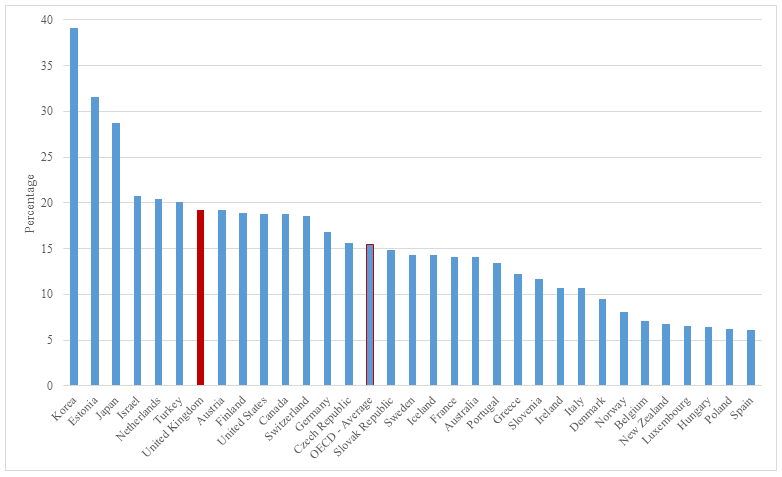

The difference between women and men’s pay – the gender wage gap – for full-time workers is 19 per cent. This is down from 27 per cent twenty years ago, which is a big improvement but compared with other OECD countries, it is among the worst (see Figure 1). The gender wage gap tends to increase with age. For people just starting to work after finishing school, there is essentially no difference in pay. But over time, gender pay differences emerge with the biggest gaps after 25-30 years when workers are in their forties. This reflects gender gaps in career breaks taken to care for young children.

Figure 1: Gender wage gap for full-time workers

Notes: Full-time employees aged 15-64. The gender wage gap is unadjusted and defined as the difference between male and female median wages divided by the male median wages.

Source: OECD, 2010.

To help reduce gender gaps due to these career breaks, recent legislation offers generous paternity leave rights to fathers. Since 2011, as well as the standard two-week paid paternity leave, fathers are entitled to up to 26 weeks of paid additional paternity leave if the mother (or co-adopter) returns to work. From this year, employers must offer shared parental leave of up to 50 weeks for children born after 1 April 2015. But since the take-up rates of paternity leave are low, there is some concern that the policy will be largely ineffective. It has been reported that less than 1 per cent of men take the current paternity leave of 26 weeks.

In March this year, a change in the law pushed by the Liberal Democrats called for greater transparency on wage gaps within firms. The regulation, which is likely to come into force within the next 12 months, would fine large firms up to £5,000 for not disclosing the average pay for male and female workers. It is unknown what effect this policy will have on helping to close the gender pay gap. But some caution is likely to be needed to ensure that greater transparency does not come at the cost of firms making compositional changes to their workforce or shedding discretionary flexible work policies, such as part-time work or generous maternity leave pay.

As with the gender pay differences, caring for children, especially pre-school age children, form an important part of the explanation for the gender gap in employment. In the mid-1990s, the proportion of prime age (25-65) women with children aged 0-4 in the UK who work was only around 50 per cent compared with 85 per cent of women without children in the age group. In-work benefits for families with children, which were conditional on working, such as the Working Families Tax Credit, in the late 1990s helped to reduce this gap. However, the gap is still 20 per cent. A number of other policies as part of the in-work benefit schemes have been introduced to help further reduce the gap. For example, workers are given up to £55 a week in childcare vouchers after taking a ‘salary sacrifice’ of the same amount from pre-tax salary.

In recognition that improvements in childcare provision will help give women with young children the option to participate in the labour market and/or to work longer hours, in the coming election, the main political parties have promised new family-friendly policies. For instance, Labour have promised more support for older children – the extension of free childcare from 15 to 25 hours for working parents with 3 and 4 year olds and the introduction of a primary childcare guarantee that primary school aged children can access childcare from 8am to 6pm through their local school. In contrast, the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats have focused on younger children. The Conservatives plan to introduce a new scheme for tax-free childcare from the autumn of 2015 and say that they will focus on offering a ‘choice’ for parents about whether to return to work or stay at home. The Liberal Democrats have pledged 20 hours of free childcare to all parents with children aged 2-4.

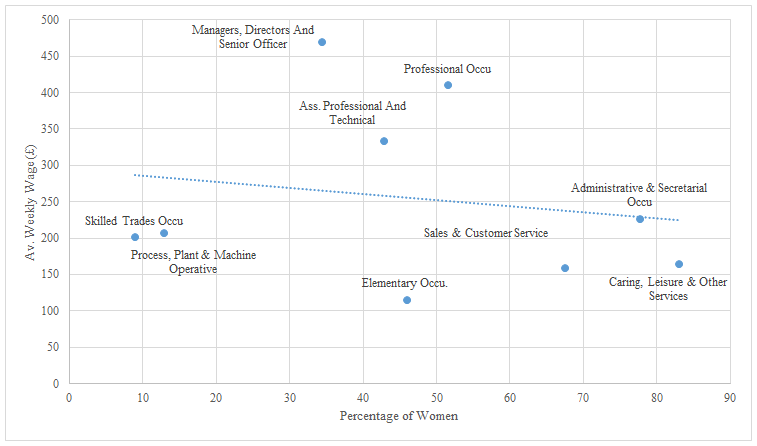

Beyond facilitating childcare constraints, there are a number of other gender differences in labour market outcomes and behaviour that need to be addressed. For instance, there are important differences in the types of occupations that men and women choose (‘occupational segregation’) and these tend to associated with pay differences (see Figure 2). With the exception of heavy manual work, such as skilled trade occupations and operatives, there is a negative relationship between average occupation wages and the proportion of women in those occupations.

Figure 2: Percentage of women and wages by occupation

Notes: Wages defined as average (gross) weekly pay for all adults aged 25-65 years working in each of the nine major occupational groups. The Figure also shows the percentage of women aged 25-65 years working in each of these occupational groups.

Source: Labour Force Survey, 2014 (Quarter 2).

Women are also more likely to opt for more job flexibility. Around 60 per cent of women with children aged 2-4 worked part-time, compared with about 25 per cent of women with no dependent children and only 7 per cent of (all) men. Part-time work is associated with a significant pay penalty. Studies have found a significant hourly pay difference of around 25 per cent between full- and part-time workers.

Addressing the factors that explain gender differences in pay or participation are an important first step to closing the gaps. However, there are differences that hard to pinpoint. These could be due to pure discrimination by employers who treat otherwise identical workers differently depending on whether they are a man or woman. Or some of these inequalities could also be related to differences in productivity or preferences between men and women, which are hard to measure.

This article is part of the CEP’s series of briefings on the policy issues in the May 2015 General Election. See the longer version here. Or watch the video:

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Ghazala Azmat is a Reader (Associate Professor) of Economics at Queen Mary University of London. She joined Queen Mary in 2011 having previously worked in Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona. Ghazala is also a Research Associate at the Centre for Economic Performance (CEP) at the London School of Economics and a Research Fellow at CESIFO (University of Munich).

Ghazala Azmat is a Reader (Associate Professor) of Economics at Queen Mary University of London. She joined Queen Mary in 2011 having previously worked in Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona. Ghazala is also a Research Associate at the Centre for Economic Performance (CEP) at the London School of Economics and a Research Fellow at CESIFO (University of Munich).