Paul Whiteley correlates Labour and Conservative vote intentions data with the actual polling day results in all UK general elections since 1945. Among his findings is the fact that the Conservative vote share consistently appears to be more predictable than that of Labour, suggesting that Labour support is more volatile than Conservative support.

Paul Whiteley correlates Labour and Conservative vote intentions data with the actual polling day results in all UK general elections since 1945. Among his findings is the fact that the Conservative vote share consistently appears to be more predictable than that of Labour, suggesting that Labour support is more volatile than Conservative support.

The veteran journalist and former president of the polling company YouGov, Peter Kellner, recently revealed one of the worst kept secrets in the polling industry. This is the fact that some pollsters tweak their eve-of-poll forecasts just before a general election because they are afraid of getting it wrong.

A pollster who gets it wrong can face significant reputational damage, even though election forecasting is only a relatively minor aspect of their business. This concern produces what is known as ‘herding’ behaviour by those who have unusual results. They are tempted to adjust their voting intention data and follow the crowd, even if this is not always a good idea. The ’horse race’ aspect of polls is important because it attracts a lot of public attention. A recent forecast from Electoral Calculus puts the chances of a Labour majority following an immediate general election at 55%, and a Conservative majority at 7%. Clearly a likely outcome of a general election if it were to be held now would be a hung Parliament.

But how accurate are the polls in the long run, as opposed to the immediate future? This is a relatively neglected issue since all pollsters emphasise that they are taking the political temperature of the country at a single point of time when voting intentions can change rapidly in the future. This argument should be set against the fact that despite a lot of volatility in voting intentions in the polls, there is nonetheless a great deal of inertia in electoral politics. Poll results in the past are strongly correlated with current poll results. So, it is reasonable to ask how accurate the polls are when forecasting election outcomes well into the future.

We can examine this issue by looking at the relationship between voting intentions in the polls at different points of time prior to an election and the actual results on election day. This can be done by correlating voting intentions data from the polls with the actual election results for the 21 elections since the end of the Second World War. To illustrate how this works, if the pollsters got the results spot on, say, a month before the election, then the correlation between the polling and the actual results would be 1.0 – a perfect one-to-one relationship. If, on the other hand, the pollsters always got it wrong, the correlation would be 0, indicating no relationship at all between polling and voting.

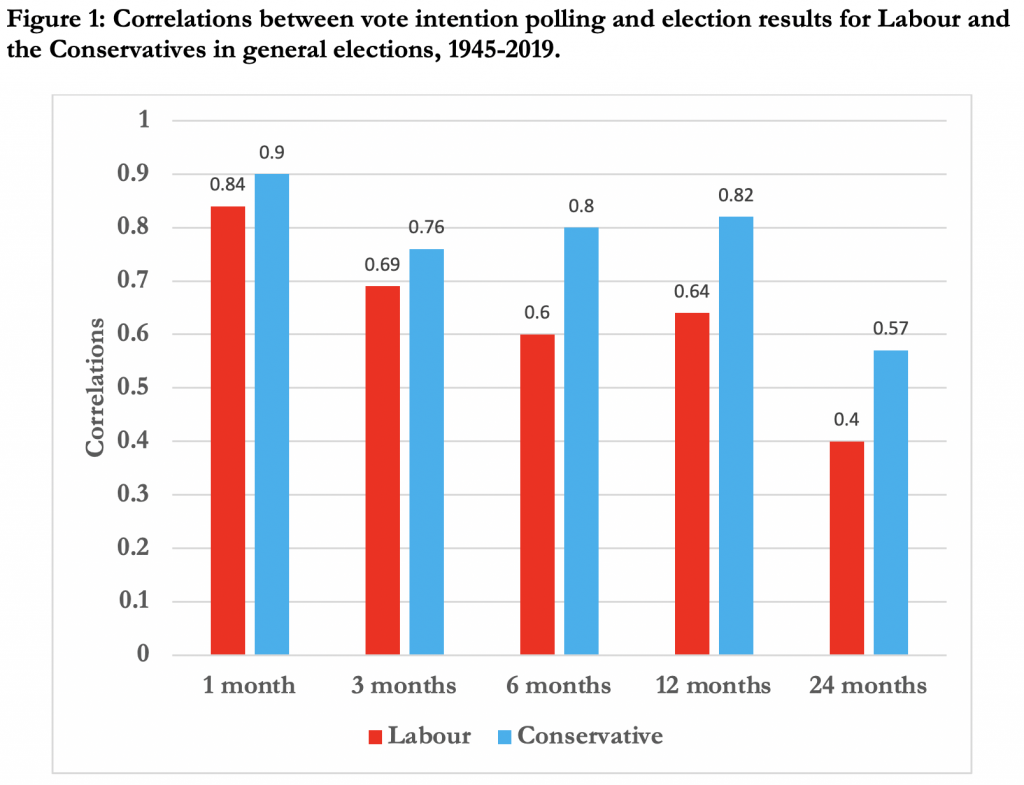

Figure 1 shows the correlations between voting intentions and the election results over five different time periods between the time the poll was produced and the date of the general election. The data used comes from Pollbase, a database on voting intentions created by the prolific polling analyst, Mark Pack, and the data goes back to 1943. The figure correlates Labour and Conservative vote intentions in the polls with the subsequent party vote shares in the elections. Not surprisingly, the polling is more accurate the closer to the date of the general election. For example, in the case of the Conservatives polling data from one month prior to the election has a correlation of 0.9 with the actual outcome. Labour is only slightly less accurate with a correlation of 0.84.

There are some interesting features in the chart. Unsurprisingly, the two-year out correlations are much weaker than one-month out correlations. That said, there is still a sizeable relationship between the current polls and those in an election two years into the future. A second feature is that the Conservative vote share consistently appears to be more predictable than the Labour vote share, although it is important not to exaggerate this difference. It means that Labour support is more volatile than Conservative support over this period of three quarters of a century. A third point is that, surprisingly, it looks like the one-year out polling is almost as accurate as the three-months out polling. In the case of the Conservatives, the one-year out correlation is actually stronger than the three-month out figure, which means that we can learn a lot from polling next year about a general election in the summer of 2024.

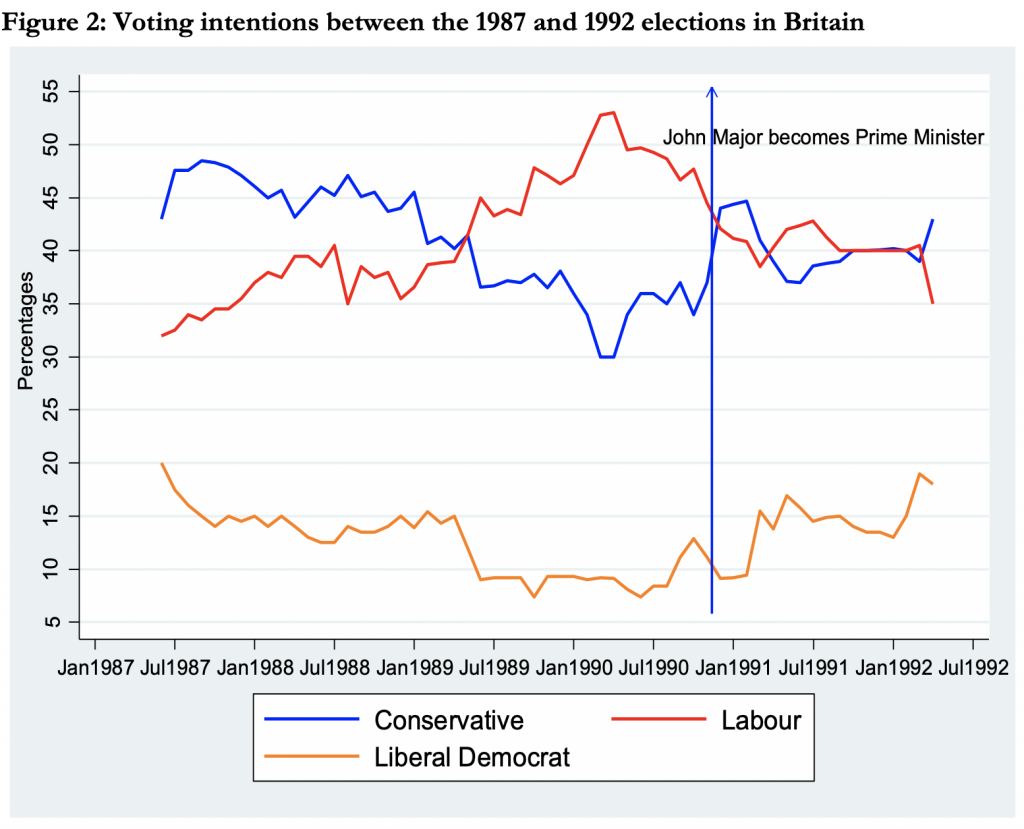

Now that Boris Johnson has resigned as Prime Minister, a new party leader can potentially change things. After Margaret Thatcher stood down as Prime Minister in 1990, voting intentions for the Conservative Party moved up after she was replaced by John Major and the party started to reinvent itself, as Figure 2 shows.

This change of leadership proved successful since John Major went on to win the 1992 election. It remains to be seen if the new Conservative party leader can do the same.

__________________

About the Author

Paul Whiteley is Emeritus Professor in the Department of Government at the University of Essex.

Paul Whiteley is Emeritus Professor in the Department of Government at the University of Essex.