Recent polling on views around foreign policy issues cast light on the primary lines of division shaping different attitudes among the UK population. John Denham and Tim Oliver look at the evidence and discuss how these divergences might affect UK foreign policy and its development in the future.

Analysis of UK foreign policy usually assumes policy is set at a UK-wide level. Yet different parts of the UK may be home to distinct views as demonstrated, for example, by the majorities in Scotland and Northern Ireland that voted Remain in the 2016 referendum on EU membership, whilst majorities in England and Wales voted Leave.

England’s size and political dominance have always given it huge influence in UK politics but its role in shaping UK foreign policy is rarely addressed. England’s views may also reflect different national identities, with those identifying as English more likely to vote Leave, and those identifying more as British voting Remain, for example.

This raises a number of questions: Could differences in national identities within England also be shaping UK foreign policy on geopolitical relationships, trade, economic policy, defence and aid? Will England’s views support or constrain UK policy-making? And might political forces mobilise contested views (as in the EU referendum and the “Get Brexit Done” election of 2019)?

Different parts of the UK may be home to distinct views.

Exploring the link between identity and attitudes

Recent polling commissioned by the Centre for English Identity and Politics at Southampton University and the Institute for Diplomacy and International Governance at Loughborough University London explores variation in English views on UK foreign policy. The polling, conducted by YouGov in October 2022, surveyed 1455 adults in England and covered three critical dimensions of these views:

- The importance of foreign policy relationships with key global players, potential partners, and potential adversaries

- Voters’ views on defence posture and international aid

- Voters’ priorities on reducing trade barriers, national resilience, and national ownership.

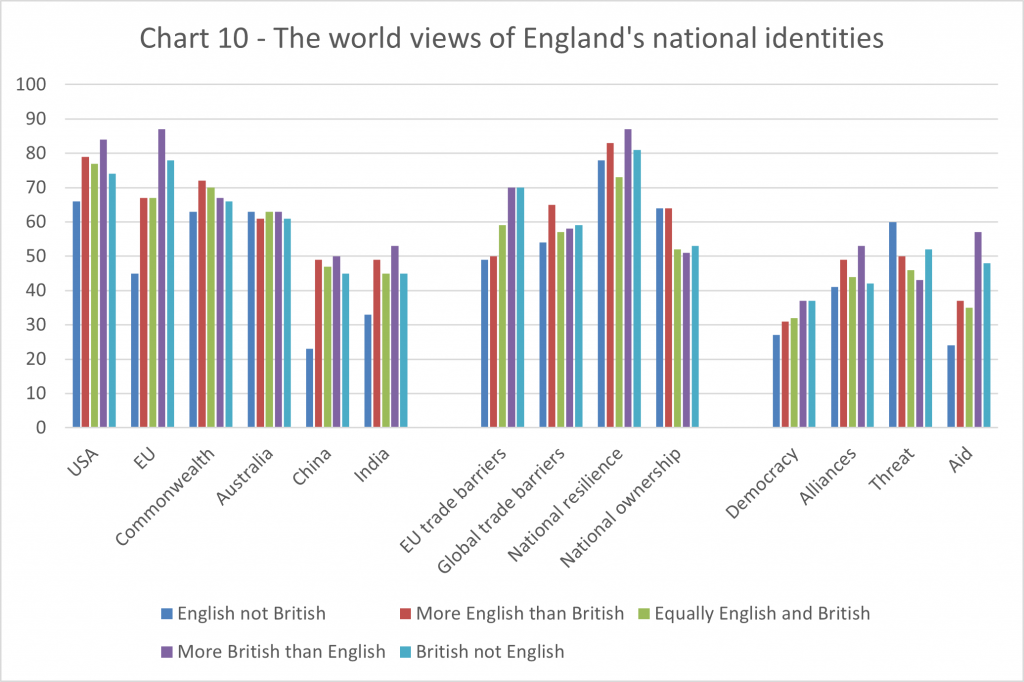

Each was examined by voters’ self-placement on the Moreno scale of English-British identity, and by their Leave/Remain vote in the referendum. In each case, our analysis has focussed on the percentage of respondents who gave each answer 4 or 5, the two highest priorities. The breakdown across the options among which respondents were invited to self-identify was as follows: English not British (14 per cent), more English than British (12 per cent), equally English and British (40 per cent), more British than English (10 per cent), British not English (12 per cent), Other (8 per cent) and Don’t know (5 per cent).

Geopolitical relationships

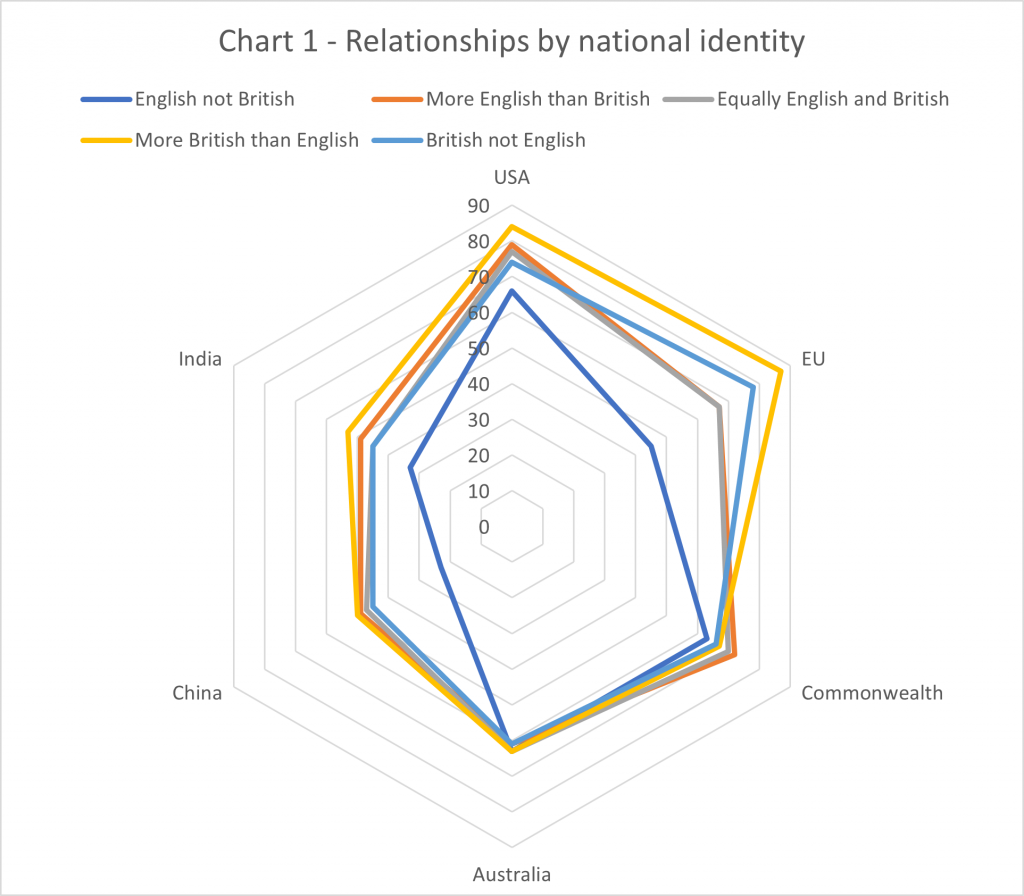

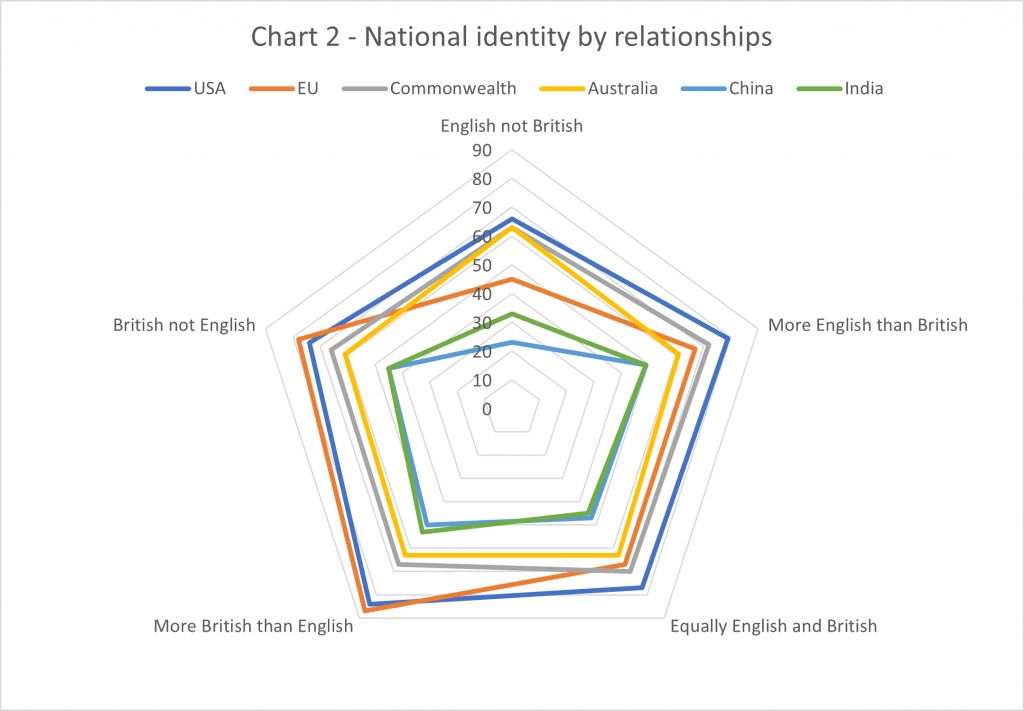

We asked: “On a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 is ‘not at all important’ and 5 is ‘very important’, how important, if at all, do you think the UK’s relationship with each of the following is? The USA, the EU, the Commonwealth, Australia, China, and India.”

As the chart below shows, the largest divergence remains over relations with the EU, ranging from 45 per cent of the “English not British” to 87 per cent of the “more British than English” prioritising the relationship (NB. All charts omit “Other” and “Don’t Know”)

The chart above shows that all identities give the UK’s relationships with India and China lower priority than those with Australia, the Commonwealth and the USA. The Government’s Integrated Review of Foreign Policy priority to engagement with the Indo-Pacific region, is not yet reflected in the world view of England’s voters.

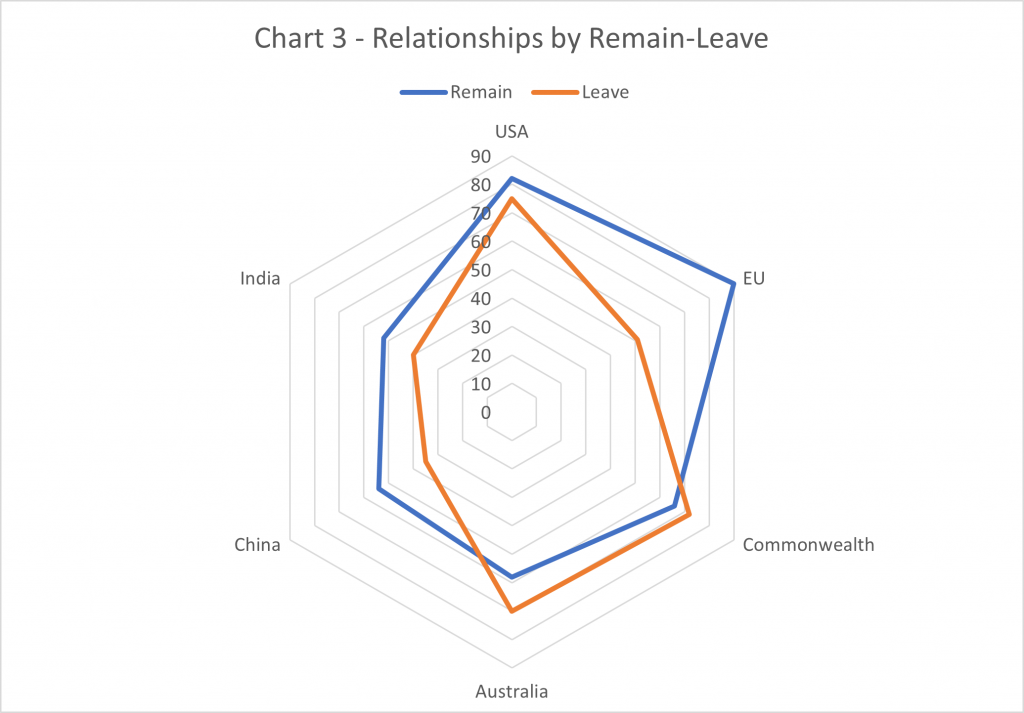

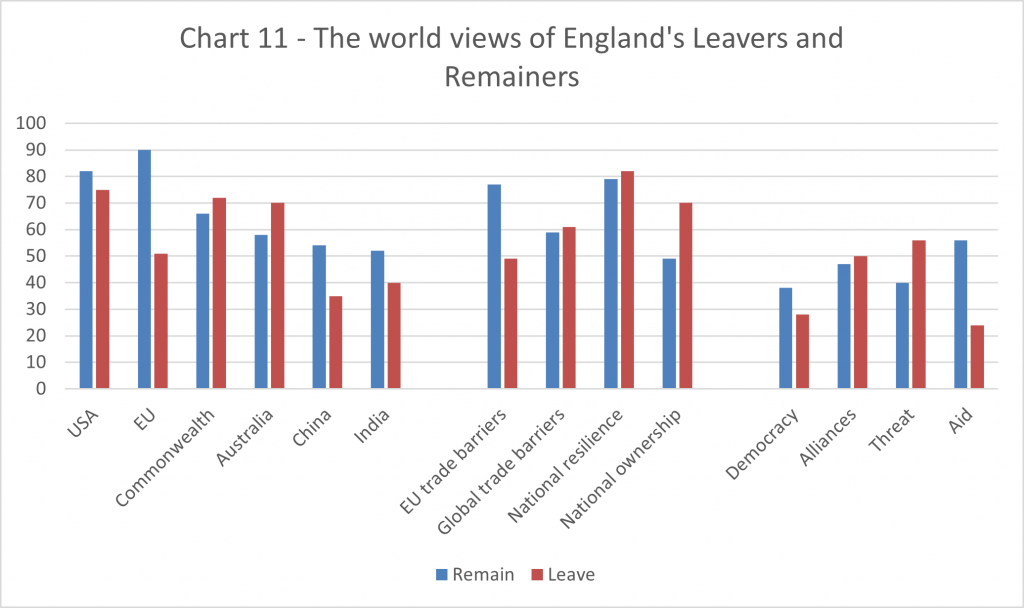

The different geopolitical priorities of Remain and Leave voters seen in the chart above broadly follow the spread of English and British leaning voters but the differences are starker. The EU referendum may have reflected a sharper divergence of world views that does not entirely have its roots in England’s national identities.

Defence and aid

The polling explored views on topics ranging from “liberal interventionism” to aid and national defence.

“On a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 is ‘not at all close to my view’ and 5 is ‘very close to my view’, how closely, if at all, do each of the following statements reflect your views?

- We should be prepared to deploy our armed forces to support democracy and human rights in other countries

- We should be prepared to deploy our armed forces to support our military alliances and friendly nations

- We should only deploy our armed forces when the UK is directly threatened

- Overseas aid is a better way of promoting the UK’s interests and values than military action”

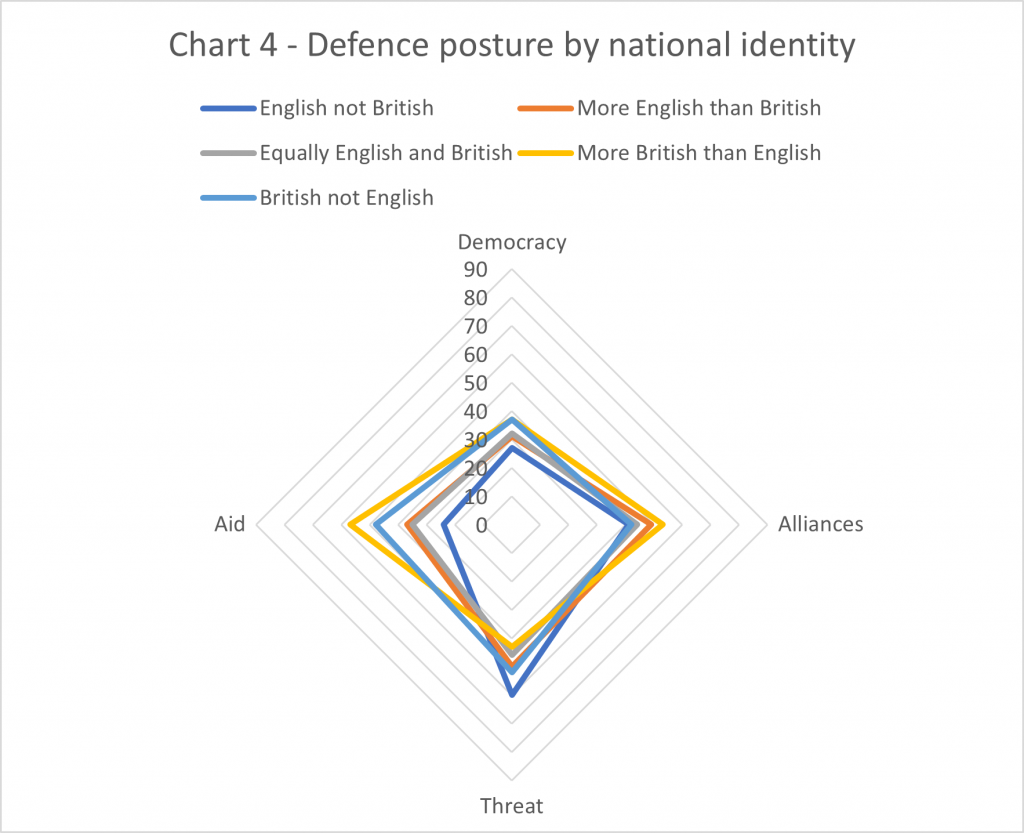

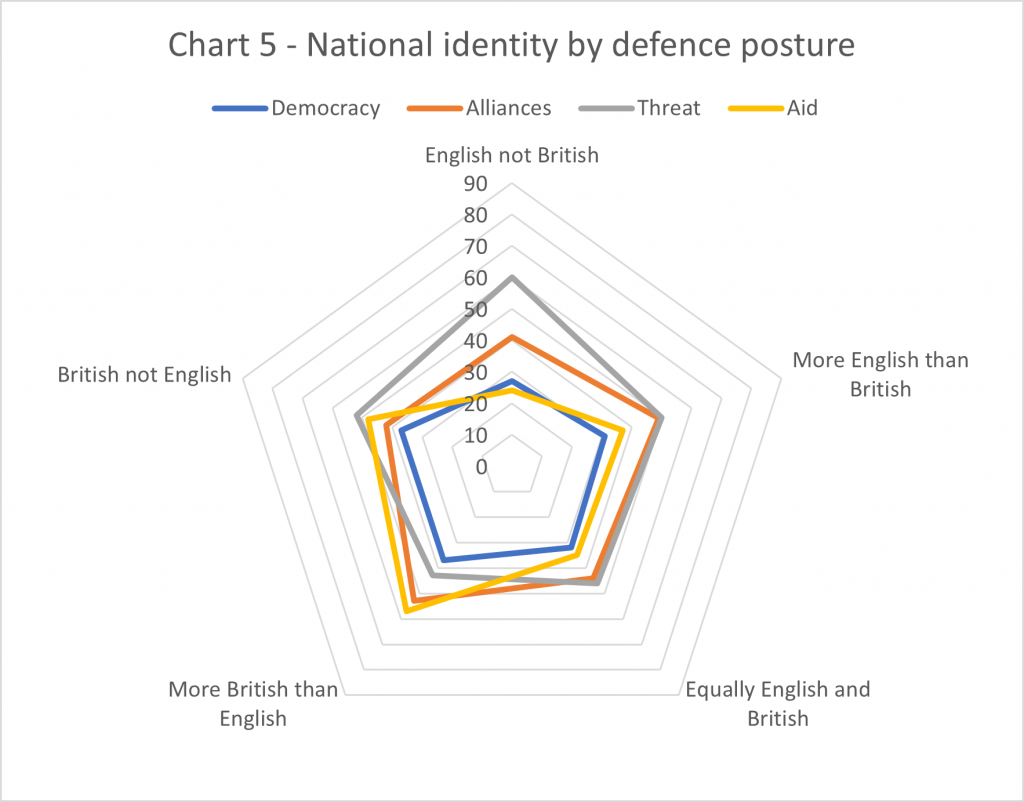

The above chart illustrates that British-leaning groups are far more positive about the role of aid than the more English groups, while the latter are most likely to prioritise national defence.

In the wake of the interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan, none of England’s identity groups give high priority to military engagement to support democracy and human rights, as the chart above shows. The influence of national identity is not clear cut, with the “more English than British” being the second strongest support of the UK’s alliances and the “English not British” the least.

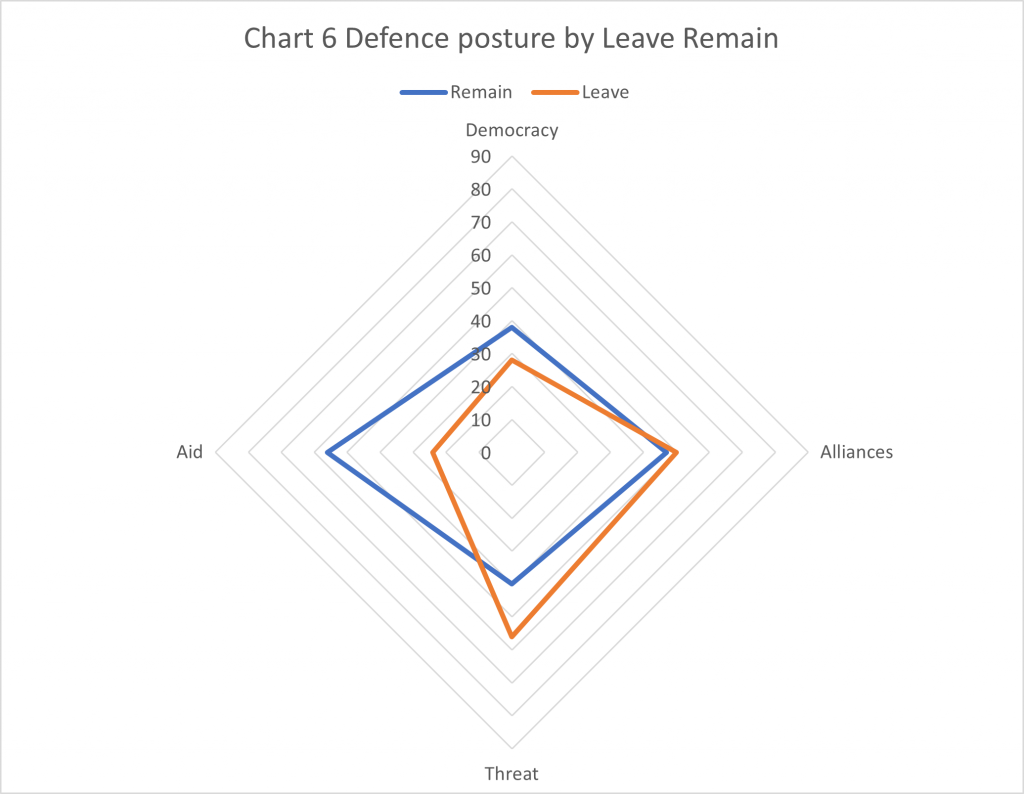

The chart above demonstrates how Leave and Remain voters have distinctive world views in this area too, diverging on aid, the threat to the nation and support for democracy and human rights.

Trade and economic policy

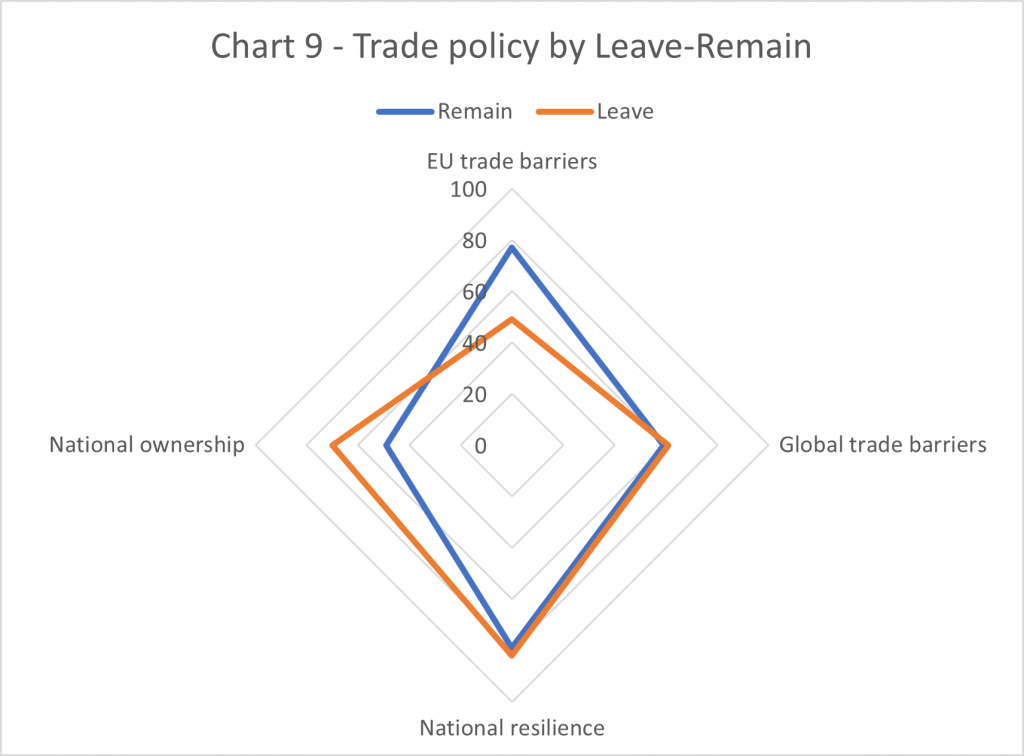

This explored both international trade and the promotion of national economic interests by asking: “On a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 is ‘not at all close to my view’ and 5 is ‘very close to my views’, how closely, if at all, do each of the following statements reflect your views?

- The UK should prioritise reducing trade barriers with the EU

- The UK should prioritise reducing trade barriers with the rest of the world

- The UK should prioritise ensuring our national economy is more resilient against global events

- The UK should prioritise preventing foreign companies owning British businesses and public services”

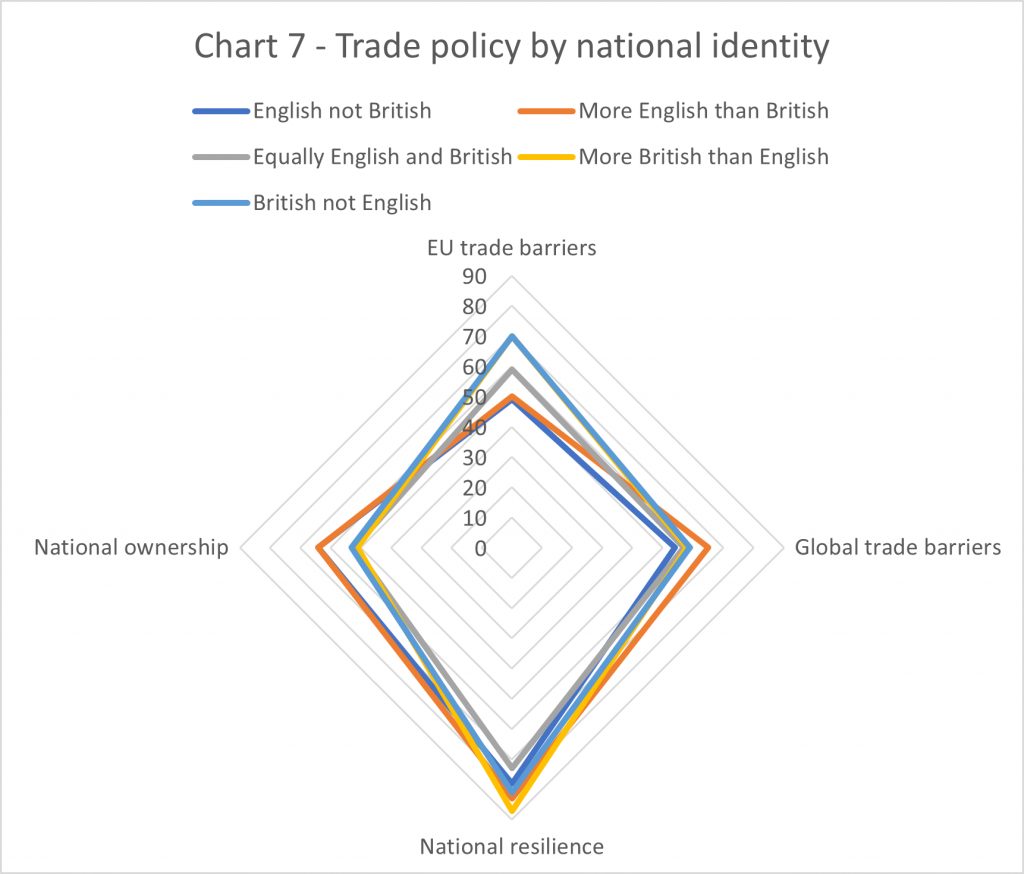

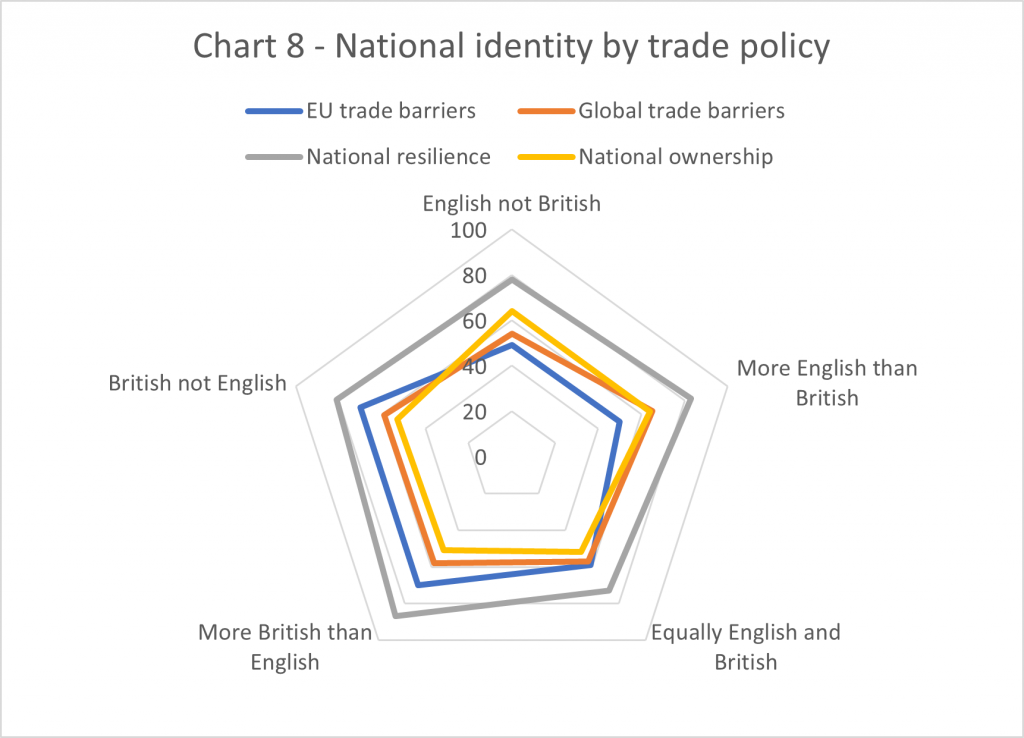

The three charts above show the more English groups giving the lowest priority to reducing EU trade barriers and higher priority to preventing foreign ownership of British businesses and public services, with sharper differences marked by the Leave-Remain divide. However, all identity groups, including both Leavers and Remainers, prioritise promoting national economic resilience most highly. There is also broad agreement on reducing global trade barriers.

How England’s world views might determine future UK foreign policy

In their 2021 book Englishness: The Political Force Transforming Britain, Henderson and Wyn-Jones suggested a distinctive English world view which includes “devo-anxiety” (the belief that devolution has given Scotland unfair financial and political advantage over England), Euroscepticism and a desire for English self-government. The two charts below plot the “world views” of England’s voters both by national identity and by the Leave/Remain division. They provide further evidence of an English world view, particularly amongst the “English not British” but it is Leavers and Remainers who hold the most contrasting views.

A contested world view only becomes a political dividing line if it becomes a clear political choice through political mobilisation or a contingent event. Our polling suggests possible – but not certain – scenarios when contested views might matter. One might be, for instance, a government building a closer political and trade relationship with the EU (the recent backlash against a Swiss-style relationship was a sign of this).

England’s shared world views may support or constrain UK policy. Some areas where these attitudes may be particularly significant include foreign intervention (there is little support for a further engagement such as Afghanistan or even Sierra Leone) or relations with China (there is not yet support for hostile rhetoric and military deployment around China and Taiwan). Among those who hold this world view, there is considerable support for an economic and trade strategy focussed on building national resilience, and the invasion of Ukraine might tap into conflicting views on alliances (support for democracy and the direct threat to the UK).

England’s shared world views may support or constrain UK policy.

With many questions yet to be answered, future polling might explore intra-UK views on, for example, nuclear defence where the politics of England and Scotland differ, and a wider range of international issues including NATO, climate change, global food, energy and raw material insecurity, and the likelihood of future mass migration.

The authors discuss the findings in more depth in this webinar.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Featured image credit: Image by Greg Rosenke, Unsplash.