It’s long been known that public support for foreign military intervention wanes with time. But are there major differences in men and women’s attitudes towards initiating and sustaining foreign wars? Ben Clements shows the persistence of a ‘gender gap’ in British public opinion by looking at the popular mood on British military interventions in Iraq, Afghanistan and Libya.

It’s long been known that public support for foreign military intervention wanes with time. But are there major differences in men and women’s attitudes towards initiating and sustaining foreign wars? Ben Clements shows the persistence of a ‘gender gap’ in British public opinion by looking at the popular mood on British military interventions in Iraq, Afghanistan and Libya.

When democracies are involved in military action overseas, it is commonplace to witness a ‘rallying round the flag’ effect in public opinion. Often this effect dissipates as casualties and expenditure accumulate, while the underlying rationale for the intervention becomes increasingly questioned. The longer that military forces are committed overseas, the more the public may feel that pressing issues at home are not being given requisite attention by political leaders. This feeling may be particularly acute during a period of economic hardship and constrained public expenditure.

This rallying effect should not obscure the fact that, in any given conflict, some groups in the population tend to be more supportive of military action than others. One of the most well-established findings from cross-national research into public opinion towards military intervention is that there are often significant differences in levels of approval or disapproval between men and women. This is commonly referred to as a ‘gender gap’, with men more likely to be supportive of military action overseas.

This ‘gender gap’ has persisted over time – in relation to interventions undertaken in the Cold War and post-Cold War eras – and has been found to exist cross-nationally. A long tradition of research has demonstrated the presence of a gender gap in public attitudes in the US in relation to the wars in Korea, Vietnam, the Gulf conflict, and interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan. In Britain, research has also shown that men were more likely to approve of military action overseas from the Falklands War, the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, through to the recent NATO-led campaign in Libya.

Support for the post- 9/11 wars has been greatest amongst men

While there are fluctuations over time, men have clearly been more supportive of the two overseas conflicts in which British troops have played a major role in U.S.-led efforts to fight terrorism abroad since 9/11.

Iraq

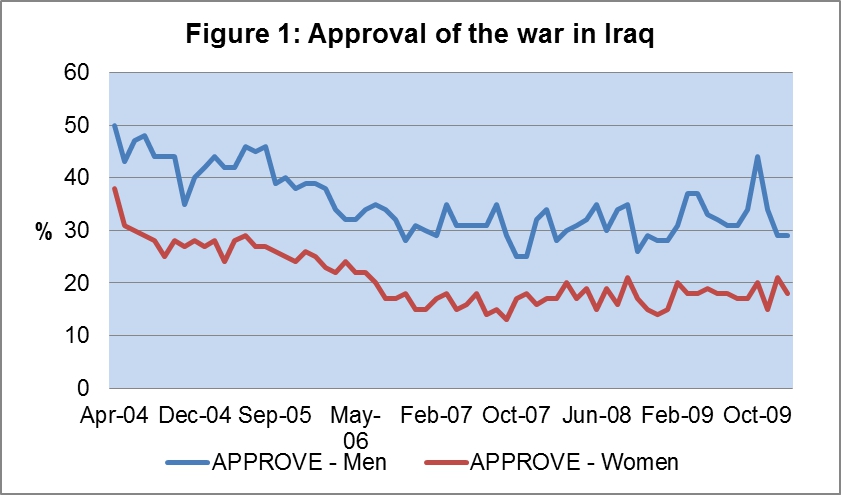

Figure 1 charts attitudes towards Britain’s role in the Iraq War, using data from the British Election Study’s Continuous Monitoring Survey (BES CMS), which has taken monthly snapshots of public opinion since 2004. Approval of the war trends downwards from 2004-07, before plateauing somewhat, although opinion continues to fluctuate.

Source: British Election Study Continuous Monitoring Survey.

Question: ‘Please tell me whether you strongly approve, approve, disapprove, or strongly disapprove ofBritain’s involvement in the war with Iraq.’

Across time, men are more likely than women to approve (combining those who ‘strongly approve’ or ‘approve’). The approval scores for men and women in the first CMS survey in April 2004 were, respectively, 50 per cent and 38 per cent, a differential of 12 per cent. In the final CMS reading of the popular mood on the Iraq War, taken in January 2010, approval levels were 29 per cent for men and 18 per cent for women, a differential of 11 per cent. Support for the war dissipated amongst both groups over time, but the ‘gap’ in attitudes remained. Polling undertaken in the months leading up to the invasion ofIraq in March 2003 similarly showed that men were more in favour of military intervention.

Afghanistan

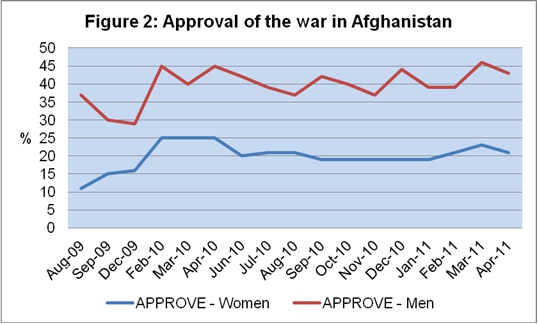

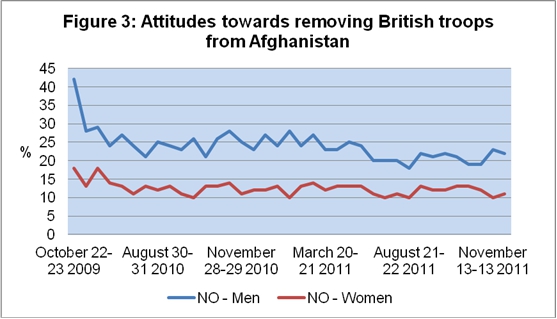

Figure 2 reports the proportions of men and women who ‘approve’ of Britain’s role in the war in Afghanistan. Figure 3 shows the proportions responding ‘no’ when asked if they think that British troops should be brought home from Afghanistan. Despite differences in emphasis and wording, both data series show that men are more supportive of Britain’s role in Afghanistan: more likely to approve of the war and to favour troops remaining there.

Source: British Election Study Continuous Monitoring Survey.

Questions: ‘Please tell me whether you strongly approve, approve, disapprove, or strongly disapprove of Britain’s involvement in the war against the Taliban in Afghanistan?’ and ‘Do you strongly approve, approve, disapprove or strongly disapprove or Britain’s involvement in the war in Afghanistan?’

Source: YouGov.

Question: ‘Should British troops be brought home from Afghanistan?’

Based on the CMS figures (combining those who ‘strongly approve’ or ‘approve), in August 2009 37 per cent of men and 11 per cent of women approved of the war in Afghanistan, a difference of 26 per cent. In the last reading undertaken, in April 2011, 43 per cent of men and 21 per cent of women approved – a difference of 22 per cent. This difference was also evident in the early stages of the conflict. For example, polling conducted in autumn 2001, when the intervention inAfghanistan was underway, showed that men were more supportive than women.

British intervention in Libya

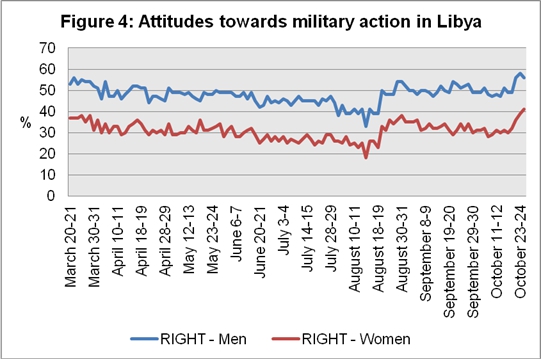

British forces were involved from March 2011 in NATO-led action (with a UN Security Council mandate) against the Libyan regime of Muammar Gaddafi, involving the enforcement of a no-fly zone and air strikes against regime forces and infrastructure. Figure 4 shows the proportion of men and women who believed it was right to take military action in Libya, for March-October 2011.

Source: YouGov

Question: ‘Do you think Britain, France, the US and other countries are right or wrong to take military action in Libya?’

Again men are more likely to support action military in Libya, although opinion in both groups shows common ‘spikes’ in response to key developments (e.g. the taking of Tripoli in late August and the killing of Gaddafi in October). The first reading taken by YouGov on this question, on 20-21 March, showed that 53 per cent of men and 37 per cent of women thought it right to take military action, a difference of 16 per cent. The final reading on this question, on October 26-27, saw 56 per cent of men and 41 per cent of women in favour, a difference of 15 per cent.

Identifying and measuring the presence of a ‘gender gap’ on overseas military intervention only takes us so far. The real challenge is to try and explain this recurring feature of public opinion in Britain and other countries. In particular, further research is needed to show whether this ‘gap’ is domain-specific: does it only tend to apply to questions of war and military intervention, where states exercise ‘hard power’. Or are there significant cross-national differences in men’s and women’s attitudes on other aspects of international affairs, where countries can exercise ‘soft power’? Answering these questions will give researchers, and indeed politicians, better insight into what kinds of policies tend to be supported more by women or men, and what this means for winning voters’ favour.

Please read our comments policy before posting.

________________________________________________

Ben Clements – University of Leicester

Ben Clements – University of Leicester

Dr Ben Clements is Lecturer in the Department of Politics and International Relations, University of Leicester. His research interests include public opinion on the EU and foreign policy issues; voting, elections and political participation in Britain; and the impact of religion on attitudes and political behaviour in Britain. He previously worked as a Research Fellow at the School of Education, University of Birmingham. He is currently researching a monograph on the impact of religion on political attitudes and behaviour in Britain(for Palgrave Macmillan).

1 Comments