It’s generally difficult to measure opinion in constituencies, so how can we tell how eurosceptic a specific constituency like Rochester and Strood is? In this article, Chris Hanretty explains the use of novel techniques which build on existing national survey samples to estimate the percentage of voters in each constituency who would currently support exit from the EU. By this measure, Clacton is ranked as the most eurosceptic constituency in Britain while Rochester and Strood only comes in at number 250.

It’s generally difficult to measure opinion in constituencies, so how can we tell how eurosceptic a specific constituency like Rochester and Strood is? In this article, Chris Hanretty explains the use of novel techniques which build on existing national survey samples to estimate the percentage of voters in each constituency who would currently support exit from the EU. By this measure, Clacton is ranked as the most eurosceptic constituency in Britain while Rochester and Strood only comes in at number 250.

At the time of writing, UKIP is expected to win a by-election in Rochester and Strood, caused by the defection of sitting Conservative MP Mark Reckless. This is despite the fact that in 2010 UKIP did not contest Rochester and Strood. The very suddenness of UKIP’s rise has meant that the party’s track record thus far is patchy and only partly informative.

Because of this, we don’t have a great mental map of which parts of the country are more likely to be fertile ground for UKIP. Most students of British politics will intuitively believe that Wales and the west coast of Scotland, since they are bedrocks of Labour support, are probably left-wing. The reverse is likely true for the Home Counties and the Conservatives. But if we had to pick out the most eurosceptic areas of Britain we would face a much harder task. And we most likely wouldn’t know how eurosceptic a specific constituency like Rochester and Strood is.

That’s because it’s generally difficult to measure opinion in constituencies. It’s relatively easy to measure opinion for one large area – say, the UK as a whole. Polling companies regularly sample one or two thousand members of the UK population to create an estimate of national opinion. They know that if they get a representative, or near-representative sample, what their sample thinks will be a good guide to what the country thinks.

In principle, we could use the same procedure to estimate constituency opinion. We could sample one or two thousand people in each constituency, and as long as our sample was representative of the population in that constituency, we could have confidence in our estimates. But this would mean sampling over half a million people nationally. Even if we could find a funder with deep enough pockets, no polling company would accept such a commission.

A more realistic approach is to try to make use of existing national survey samples to say something about constituency opinion. An excellent starting point here is the 2015 British Election Study (BES), which interviewed a huge number of English, Welsh and Scottish respondents – around 30,000 – between May and June 2014. The trouble is that even with 30,000 respondents in the national sample, we are left on average with only 47 respondents from each of the 632 English, Welsh and Scottish constituencies.

A first improvement on simply splitting the data up into sub-samples comes from supplementing these constituency sub-samples with other sources of information. First, we can take information about demographic types of respondents and the views they express and combine this with information about the demographic make-up of each constituency. Suppose we find out that people aged 75 and over who left school without any qualifications are quite likely to disapprove of the European Union compared to the rest of the population. In that case, we might expect that constituencies which have – according to census data – lots of older, less well-educated people are more likely to disapprove of the EU, compared to other constituencies.

Second, we can use more general information about the constituency characteristics. Suppose we find that BES respondents from more sparsely populated, rural constituencies tend to disapprove of the EU more than respondents from more densely populated urban constituencies. Then we have reason to expect that constituencies with similar population densities are likely to be similar to one another in terms of prevailing levels of Euroscepticism, and that information from a respondent from one densely populated constituency tells us about opinion not just in that constituency, but in other similar constituencies.

Third, we can use information about the geographic location of constituencies. We allow for constituencies from the same region to share some similarities in terms of prevailing political opinion. Within regions, we also allow for more similarities in public opinion between neighbouring constituencies than between constituencies that are further apart. In other words, we assume that the the political opinion of a respondent from constituency X tells us not only about opinion in constituency X, but also tells us something about opinion in other constituencies nearby.

We combine all of these sources of information with our raw BES survey data using some statistical modelling – specifically, an approach called multilevel regression and post-stratification. This approach has already been used by other researchers to estimate public opinion in US States, US congressional districts and German parliamentary constituencies.

To get a sense of how eurosceptic each parliamentary constituency is, we use all of these techniques to estimate the percentage of voters in each constituency who would currently support British exit from the EU in a referendum. We begin with the following question asked to 21,000 respondents in the 2015 BES:

If there was a referendum on Britain’s membership of the European Union, how do you think you would vote?

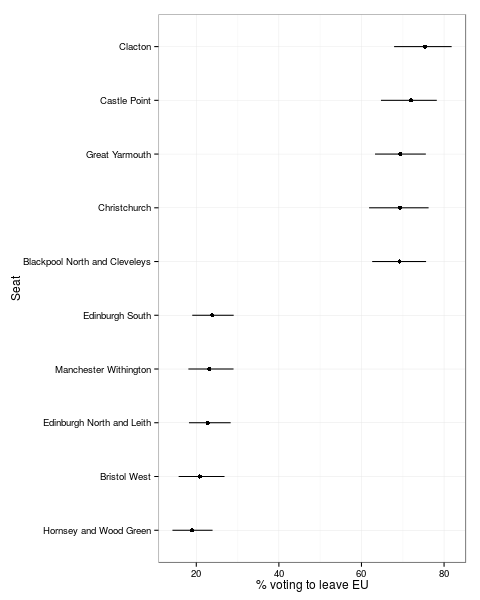

Figure 1: Most and least Eurosceptic constituencies

Figure 1 plots our estimates of support for British exit from the EU for the most extreme constituencies. Interestingly, by this measure Clacton – where sitting Conservative MP Douglas Carswell defected to the United Kingdom Independence Party – has a good claim to being the most eurosceptic constituency in the UK. Our best estimate for Clacton is that around 75% of respondents would vote to leave the European Union. We cannot rule out the possibility that other constituencies are more eurosceptic than Clacton: our 95% credible interval runs from 68 to 82 percent. But there is clear blue water between Clacton and Hornsey and Wood Green, the constituency we estimate as least favourable toward an exit from the EU.

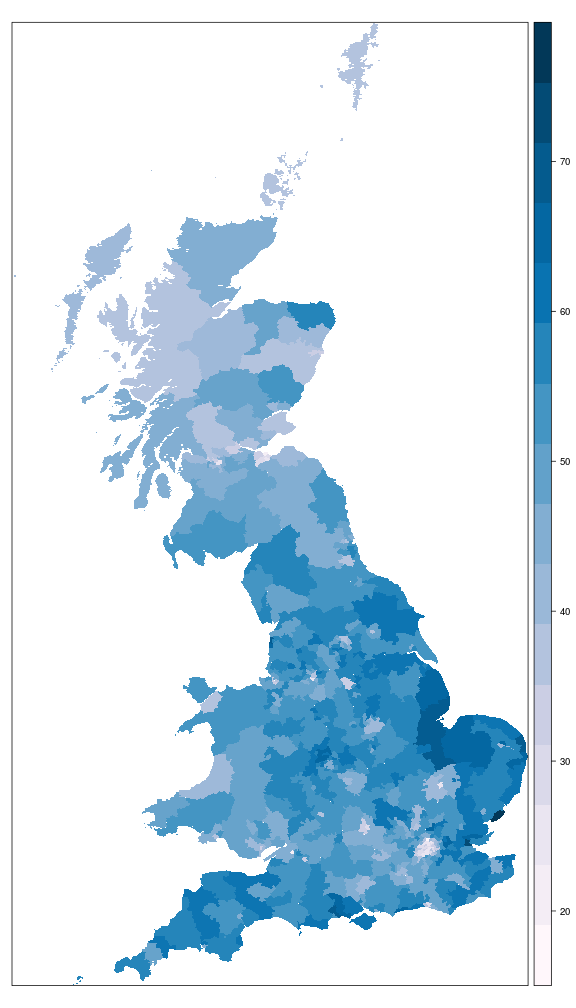

Figure 2: Map of Euroscepticism

Figure 2 maps support for British exit from EU across all 632 British constituencies. The geography of euroscepticism is similar to the geography of UKIP support identified by Rob Ford and Matt Goodwin in their book Revolt on the Right. Euroscepticism is concentrated in constituencies with a larger percentage of elderly white residents with low levels of education. These constituencies are often located in Eastern and coastal areas. In contrast, constituencies where support for an EU exit is particularly low tend to be densely populated, relatively young, and relatively cosmopolitan.

Now, this is only a map of euroscepticism – and euroscepticism is not identical with support for UKIP. At least, UKIP better hope it’s not the same thing: by our measure, Rochester and Strood is only the 250th most eurosceptic in the country.

This post is based on research conducted together with Nick Vivyan (Durham) and Ben Lauderdale (LSE), and draws upon a booklet entitled Constituency Opinion and Representative Democracy in Britain. You can find the booklet, and the raw data on euroscepticism, at the project website, www.constituencyopinion.org.uk.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Chris Hanretty is a Reader in Politics at the University of East Anglia.

Chris Hanretty is a Reader in Politics at the University of East Anglia.

So the LSE thinks that Hornsey & Wood Green is the most pro-EU area in Britain…

(QUOTE: “least favourable toward an exit from the EU”)

As someone who encounters rabid pro-UKIP passions from people in Hornsey & Wood Green every time we leaflet against UKIP in Crouch End, that doesn’t cheer me up!