The Government’s pledge to extend the “Help to Buy” programme is a further mistaken investment in a policy which has had little impact on extending home ownership to lower income households, explains Bert Provan. So, the £2bn investment in “social and affordable housing” is, while welcome, wholly inadequate to meet the pressing and increasing need for low cost rented housing for households in most need.

The Government’s pledge to extend the “Help to Buy” programme is a further mistaken investment in a policy which has had little impact on extending home ownership to lower income households, explains Bert Provan. So, the £2bn investment in “social and affordable housing” is, while welcome, wholly inadequate to meet the pressing and increasing need for low cost rented housing for households in most need.

The wish to stimulate “low cost home ownership” is a policy goal which has remarkable appeal to governments in both emerging and advanced economies. While the first such scheme could be said to date from 1769 in response to the devastation of the Seven Years War, a more contemporary assessment in 2011 by the IMF indicates that subsidies and incentives – through tax breaks, preferential loans, or other guarantees – are common in over half the countries surveyed. And the 1982 Thatcher “Right to Buy” legislation has seen over 2 million properties sold to sitting tenants (although over 40% were subsequently sold on to become private rented properties).

Since the 1990s cross-party English housing policies have included some form of commitments to help “first time buyers” to get onto the property ladder. These policies include both subsidising the construction costs of homes for targeted sale to first time buyers, mortgages with subsidised rates or lower deposit requirements, subsidised savings schemes, and “shared ownership” programmes which let these buyers initially buy half the house (or less), then increase their equity at a later date (renting the rest in the meantime).

Credit: Pixabay/Public Domain.

Credit: Pixabay/Public Domain.

But who benefits? And what is the impact on the wider housing market? In 2017, the Social Mobility Commission published a report from LSE into the extent to which lower income households were benefiting. The report indicated that during the period 2003-4 to 2014-15 around a quarter of a million new homes were provided (13% of the total new homes) through these “affordable” housing schemes. An additional 300k households also benefited from the other subsidies to first time buyers. Similarly a 2016 report commissioned by DCLG estimated that the current Help to Buy Equity Loan scheme had generated 43% additional new homes over and above what would have been built in the absence of the policy, equivalent to contributing 14% to total new build output to June 2015 (from April 2013). So far so good.

The downsides of the policy are also evident, however. First, the benefits of the policy are enjoyed mainly by households who have incomes considerably above the national median income for working households, and who would very likely have bought their own home in any case. That is, it did not help households who actually needed help to get on the housing ladder. The 2016 report sets out that the median income of working age households in England is £507, or (adjusting for tax) under £30k a year. In contrast official (2016) DCLG tables indicate that the median income of those benefiting from these help to buy schemes is £42k. In all, only one in five of the households benefiting had incomes less than the national median.

Moreover, in the DCLG report, three in five of the households benefiting indicated that the scheme had allowed them to buy sooner than they would have because they needed a smaller deposit or could buy a better property, or one in a better area; and a similar number confirming that they would have bought in any case without the assistance of the scheme.

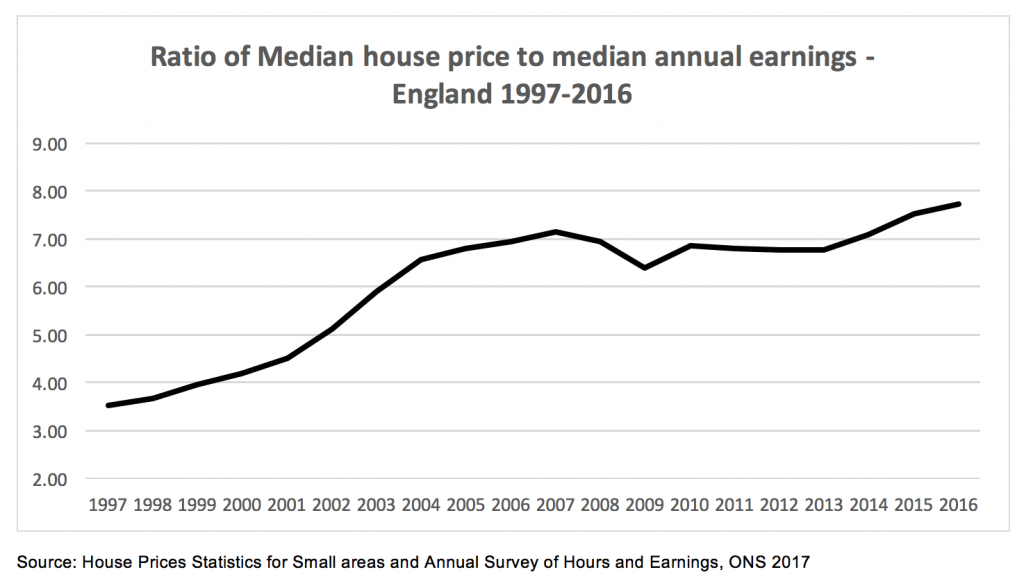

In fact, the proportion of households who are owner occupiers is dropping, down from 71% in 2003 to 63% in 2015-16. Supply is not keeping up with demand – but more importantly, wages are not keeping up with prices as was set out in the 2016 Redfern Report into the decline of home ownership, and this is making ownership increasingly unaffordable. Updated 2017 figures from ONS show this clearly continuing:

In this context, these low cost ownership schemes should be more targeted on low income groups who need specific support to move onto the housing ladder. If not, their impact may be to push up prices. In fact, there are groups for whom home ownership would be a new and difficult transition, due to no family background of ownership, or other barriers. In stark contrast, we also know from other research published by the Social Mobility Commission in 2017 that a third of first time buyers in England now receive help from parents or family members. The income limits on low cost ownership schemes do not prevent this latter, privileged, group from also benefiting from those government schemes in addition to family support – compounding the lack of targeting those most in need.

Models for more targeted schemes do exist. In Australia, the US, and other countries there are programmes which not only restrict assistance to households within a 1.5 limit above the median income, but also provide advice, practical assistance, and wider support around the risks and responsibilities of home ownership.

And what of the £2bn for social and affordable housing? Welcome as this is, it provides only around 5,000 new homes a year, in a context where waiting lists for social housing, and the pressure of rough sleeping, are both areas for considerable concern, particularly in the context of rising rent arrears. Compared to these risks to the “just about managing”, the expenditure of five times more on the better off households with incomes well above the median seems misguided, if not plain wrong. Or to quote a report to the Australian Senate in 2013:

It’s hard to think of any government policy that has been pursued for so long, in the face of such incontrovertible evidence that it doesn’t work, than the policy of giving cash to first home buyers in the belief that doing so will promote home ownership.

______

Bert Provan is an Occasional Senior Research Fellow, and Knowledge Broker, in the Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion at the London School of Economics.

Bert Provan is an Occasional Senior Research Fellow, and Knowledge Broker, in the Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion at the London School of Economics.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

The key issue with the quoted income levels is that they are not region adjusted. People working in London with household incomes of 100,000 may struggle to buy a house in a safe area while those in Manchester could easily manage on 40,000.

The key issue with the argument itself is that it assumes the priority of government is to help those social groups with low enough intellect to be considered ‘needy’. The priority of government currently should be to boost the productivity and fertility of the most productive. Most highly productive people see home ownership as the step before having kids: thus the state should ensure it happens as early as possible for our best talents. Home ownership amongst the young and talented is currently ridiculously low as they are strongly clustered in the most expensive areas of the country. To enable the most productive people to contribute most to the country, the young and talented need to have assets to work with: help to buy is a decent way of achieving this.

What a strange and contorted vision of what it is to be privileged. The ‘median’ income of ‘working-age’ households isn’t defined here, but logically includes those who are still in full-time tertiary education and those who are unemployed, as well as those who have had little or no time to build up income or deposits sufficient even to think of home buying yet, as well as single-adult households whose median income is likely to be much lower than households with two working adults. The contention that £42,000 as a median income for buyers benefitting from help-to-buy schemes represents ‘privilege’ is nonsensical unless the comparison is like-for-like – which it clearly isn’t.

Help from family members used to be a perk of the privileged classes but in the last decades has become more common, as home-owning working-class parents have begun to trade down from family homes to retirement accommodation and home-ownership aspirations among the young have been delayed.

As for the assertion that these ‘privileged’ beneficiaries of the help-to-buy scheme would have bought anyway, there should have been a caveat that, although the buyers questioned had an aspiration to buy in any event, there could be no certainty that they would ever have managed to do so without state help to buy schemes.

“The 2016 report sets out that the median income of working age households in England is £507, or (adjusting for tax) under £30k a year.”

This seems to me to be an adequate definition of those who are at the lower end of income and who are benefiting from the scheme. In contrast, the article is saying that 4 out of 5 beneficiaries have an income of £42k . This seems to me to be saying that the poorest are not benefiting from this scheme as much as the better off (even if the not very much better off are included). Whether that is a strange and contorted definition of privilege is open to debate -surely the point is that the State should be supporting the poorest and neediest the most? Would it not be better if 4 out of 5 of the beneficiaries were on the £30k income level and 1 out of 5 on the 42k level?

No, I think that’s far too simplistic. To draw a valid conclusion about who ‘should’ be benefitting from the scheme, it would be necessary to know what proportion of each income segment is ready and willing to become home-owners. Those still in full-time education or otherwise not wishing to ‘settle’ or be tied to one place should be excluded from the statistics. Single person households with an income of 30k are not ‘poorer’ nor ‘needier’ than dual income households on 42k a year. The article proposes that it is legitimate to compare apples with pears. That is absurd and should be challenged.