The Leave campaign’s understanding of “freedom” as the absence of external constraints is one-sided, writes Alexis Papazoglou. The UK has autonomously decided to be bound by EU rules and so compliance with those rules does not make it a less autonomous country. Similarly, the freedoms that the UK gains from being an EU member are greater than those it gives up. More importantly, if a Brexit were to happen, external constraints might indeed disappear but so will the UK’s power to freely act in the ways it wants.

The Leave campaign’s understanding of “freedom” as the absence of external constraints is one-sided, writes Alexis Papazoglou. The UK has autonomously decided to be bound by EU rules and so compliance with those rules does not make it a less autonomous country. Similarly, the freedoms that the UK gains from being an EU member are greater than those it gives up. More importantly, if a Brexit were to happen, external constraints might indeed disappear but so will the UK’s power to freely act in the ways it wants.

Freedom has been the core value in the rhetoric of the Leave campaign. Boris Johnson has called for people to “choose freedom” while Nigel Farage has said that 23 June could be “independence day” for the UK. But the way that the Leave campaign understands freedom is one-sided, and even mistaken. In fact, the Remain campaign’s ideal is also freedom, and ultimately its claim should be that by remaining a member of the EU, the UK would be more free than if it didn’t.

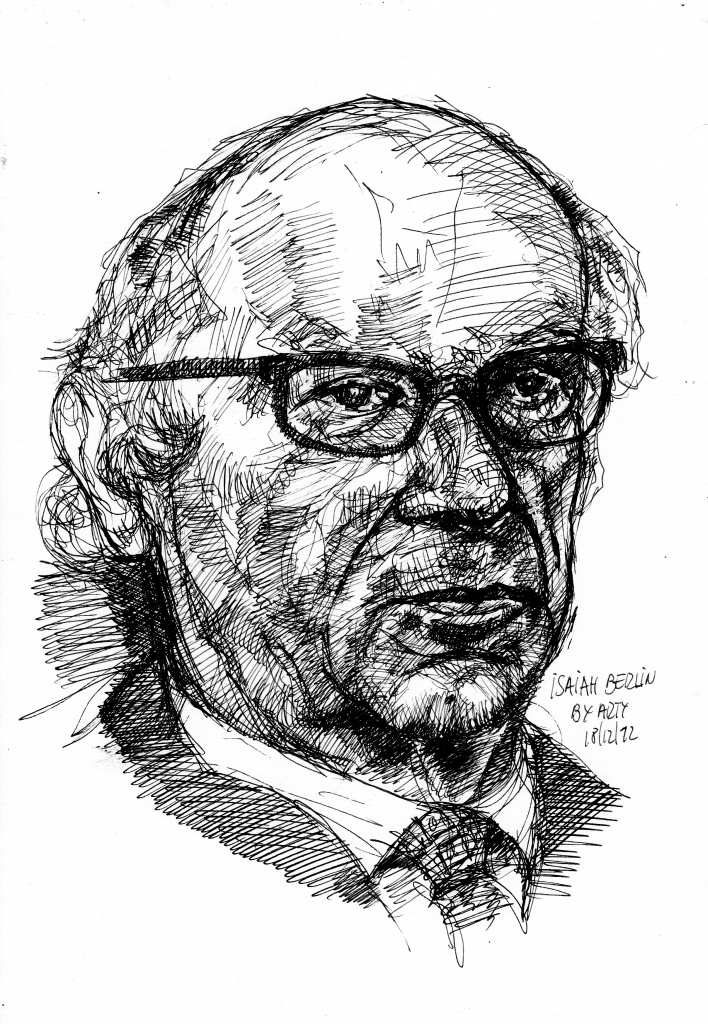

In his classic essay Two Concepts of Liberty, Isaiah Berlin made a distinction between positive and negative freedom. Negative freedom represents freedom from constraints and interferences, and positive freedom represents freedom to do things on one’s own volition. Philosophers have pointed out that Berlin’s analysis in fact contains more than just two concepts of freedom, and that the dichotomy might not be as clear-cut. But at least one way of understanding negative freedom is as freedom from external interference, and positive freedom as autonomy, the freedom to legislate for oneself, to decide the laws that one is bound by.

In his classic essay Two Concepts of Liberty, Isaiah Berlin made a distinction between positive and negative freedom. Negative freedom represents freedom from constraints and interferences, and positive freedom represents freedom to do things on one’s own volition. Philosophers have pointed out that Berlin’s analysis in fact contains more than just two concepts of freedom, and that the dichotomy might not be as clear-cut. But at least one way of understanding negative freedom is as freedom from external interference, and positive freedom as autonomy, the freedom to legislate for oneself, to decide the laws that one is bound by.

Positive freedom

One of the Leave campaign’s main arguments is that by being a member of the EU, the UK is not free to be the maker of its own laws. In Berlin’s distinction, being a member of the EU undermines Britain’s autonomy. This is to some extent true: some of the laws that the UK is bound by are not voted in Westminster. Yet that does not mean that the UK is not an autonomous, free country. The UK has freely decided to bind itself to the laws of the EU. This is a voluntary participation, and one that can be terminated at any point by a UK government, or in fact directly by UK voters this month. At the same time, if the UK votes to stay, this would not signal a loss of autonomy, as it has autonomously chosen to bind itself to EU rules.

The Leave campaign’s claim that the UK’s autonomy is compromised because it is bound by EU legislation is also mistaken because of the way that legislation is made. EU legislation is not conjured up by some arbitrary despot, or ‘faceless bureaucrats’ as it is often said. These laws are democratically decided upon in the European parliament, with the participation of the UK’s representatives, who are directly elected by the citizens of this country. The UK is active in the decision-making process that shapes EU legislation, and as in any democratically-governed institution, it is wrong to claim that participants are not free because they are bound by democratically-arrived decisions.

Negative freedom

So much for positive freedom, but what about negative freedom – that from external interference? Leavers claim that the EU doesn’t allow the UK to always do what it wants, and that amounts to limiting the UK’s freedom. That’s certainly true. So if the UK government wants to turn away EU citizens who arrive at its borders, for example, it currently cannot. But the limiting of one’s negative freedom in a political context usually also means a gain in negative freedom: the UK might have given away its freedom to close down its borders to other EU citizens, but at the same time UK citizens gain the freedom to cross the borders of all other EU countries without any interference, freely. So one way that the Remain campaign can respond to that argument is this: the freedom that the UK gains by being a member of the EU is greater than the freedom it gives up. Having access to the common market, having the freedom of movement, of trade, freedom of selling services and so on is far greater a gain in freedom than the freedom the UK gives up.

Most of those on the Leave side of the campaign recognise the enormous benefits that come with the freedoms that the common market provides. The argument often is that somehow the UK would be able to negotiate its way into enjoying these freedoms, without giving up any of its own. That would be the equivalent of wanting to live in a society where I am the only citizen enjoying all the negative freedoms everyone else does, but without giving up any of my own corresponding freedoms.

Effective freedom

At the start of this piece I defined Berlin’s concept of positive freedom as autonomy. There is at least one more way of understanding positive freedom, and that is as effective freedom. Effective freedom amounts to having the power and ability to act in the way one wants, and not merely as the absence of an external constraint. Even if one grants to the Leave campaign that the UK’s freedom would be increased in the negative sense if it left – in that it will be free of the external constraint that is the EU – its effective freedom might in fact diminish.

The argument that the Remain campaign often makes is that the UK will be less powerful to do the things it wants, including strike international trade deals and influence global issues such as climate change. So even though the UK would be nominally free to do so, effectively it wouldn’t, as it wouldn’t have the power to strike such deals or the capacity to influence the rest of the world. By being a member of the EU, then, the UK’s effective freedom is greater than if it were not, as being a member of the EU makes the UK more powerful and able to ultimately achieve its goals.

The Leave campaign has had a monopoly over the value of freedom at the rhetorical level. but when it comes to actual arguments, the campaign’s understanding of freedom is one-sided and misleading. The Remain campaign has focussed on the economic benefits that come with EU membership, shying away from engaging with arguments to do with freedom. Freedom, however, is an emotive ideal, capable of motivating voters, especially those who feel less powerful in society and who yearn for some control over their lives. Those who support the UK’s membership of the EU should not allow citizens to be misguided by the idea that a vote to leave the EU is a vote for freedom.

___

Alexis Papazoglou is lecturer in philosophy at the Department of Politics and International Relations at Royal Holloway, University of London. For a list of publications see here.

Alexis Papazoglou is lecturer in philosophy at the Department of Politics and International Relations at Royal Holloway, University of London. For a list of publications see here.

Hooray. Top essay – thank you.

http://www.bartleby.com/25/2/2.html

“Those who support the UK’s membership of the EU should not allow citizens to be misguided by the idea that a vote to leave the EU is a vote for freedom.”

That’s not our experience. We voted to shrug off continental hegemony in 1538 an it all worked out well.

“Negative liberty is freedom from interference by other people.”

The EU is primarily about interference!

It’s not good enough to characterise positive freedom by saying it “represents freedom to do things on one’s own volition.”

First, that’s circular; and second, it doesn’t make for a distinct concept from that of negative freedom. On the present understanding, positive and negative freedom are completely inter-definable. If I want to do something, and I’m able to do it because of the absence of external constraints, then I’m free in the negative sense — but obviously I’m also free to “do things on my own volition”.

Nor will it do to define positive freedom simply as “autonomy”, as the clearest understanding of ruling oneself is to not be ruled by others — which again is just the same thing as being able to do what one wants without external constraints.

The essential difference between positive and negative freedom, which as far as I can tell this article doesn’t touch on, is this: having positive freedom means more than simply being able to get what you want — it means wanting the right things, usually understood in some implicitly moral sense. The various goods that are thought to empower those who have positive freedom — such as education — are things that many people do not in fact strive for. But according to those who understand freedom positively, they ought to strive for them, for their own empowerment.

Implicit “oughts” are an essential ingredient in the positive concept. In Rousseau’s terms, being free means partaking in the “general will”, in other words not simply pursuing goals one already happens to have, but adopting larger goals as one’s own. Only with that essential extra ingredient can people be “forced to be free” or considered unfree if their “empirical selves” fall short of the “self-realisation” of their “true selves” (in Berlin’s terminology). Ideas such as “false consciousness” only make sense against the background assumption that being free means wanting the right things as well as being able to achieve them.

I agree that many opponents and proponents of Brexit are at odds because of differing conceptions of freedom, but I think we need to be a lot clearer about how they differ.

The claim that negative liberty is “trivial” compared with positive liberty begs the entire question. Berlin argued not only that positive and negative liberty are different but also that they are opposed and often irreconcilable. Therefore, a choice for one rather than another doesn’t necessarily represent a confusion; it might express a preference. Berlin himself certainly would not have endorsed Papazoglou’s apparent preference for positive over negative liberty in cases where one must choose between them. But however one sorts out all this it’s a stretch to say the least that it played a role in the vote.

Hello – the average British voter will not write an essay like this about their decision. To us it is a very simple decision because we live here and know what the score is and will be xxxx h

LOL! To paraphrase:

You were sold into slavery by your chosen leaders, therefore you freely chose slavery. You now have freedom from choice. You are made stronger by handing your responsibilities to a big unelected authority. Freedom is slavery. Ignorance is strength. It’s doubleplusgood.

The obvious problem with the eu (which bremainers, especially eu idealists/apologists love to fudge) is that in the eu we do not vote for which party will be the one in power making all the laws and policy. This obviously isnt democracy.

What does happen though is a process of internalized selection which pretty much maintains the same policy framework as per the eu treaties. If this was happening on a national level, it would be like having the same party in power but the leadership and cabinet changing every so often.

So for example, since policy hasnt really changed since 1992 (and consequently eu policy is treated like law), it would be like having the Conservatives in power for 24 years.

The deeper problem with the eu however (unless you are not interested in politics) is the disconnect between the public and eu politics. Asides from enabling politicians to be less productive and accountable as could be argued, the fact of the matter is that there is no discernible and integrated european political culture/identity that is transmitted on a daily basis through the media in the same way a national political culture/identity is.

For someone like myself who likes to freely engage politically, this is the biggest democratic deficit of the eu and one which effectively renders my freedom to engage politically almost obsolete in cultural terms. This is because there is no active media (cultural) platform from which I can engage with other people in the usual ways.

However, deeper still, even if there was a coherent and easily accessible European political cultural platform from which I can freely engage with others, what concerns me as a political person is the possibilty of political change as a result of my engagement. It would seem that by remaining, I (and others) would need to convince a majority of europeans (250 million people) in order to change anything. Whereas by leaving, I (and others) would only need to convince a majority of britains (30 million people) to change anything.

So the question that arises, which poltical system provides the greater amount of freedom to engage and lobby for change and so which will give me the greater sense that change is possible so that it is worthwhile me engaging in the first place.

Considering the diversity of needs in Europe and the impossibility of aggregating social preferences (as per Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem) then it feels the possibilty of changing anything, albeit remote, would be easier if policy-making was all done in the UK alone (including the added freedom of being able to attend top table meetings at global institutional level which eu membership restricts). Not only because most people in the UK talk and understand deep concepts in the same language but also because a coherent and integrated political culture already exists here whereas the remain option means waiting for a media facilitated integrated european culture to happen if it ever does.

In conclusion, your arguments not only rely on a partialist understanding of freedom in that you choose to discount the effective political cultural freedoms that are facilitated by the coherent political cultures that exist on a national level but not the european but you also discount the importance of citizen engagement in being able to influence policy-making. These two very important ‘effective’ freedoms that you choose to ignore is exactly why the Brexit campaign can and does use the concept of freedom much more effectively than the Bremain campaign because these freedoms do not effectively exist in relation to eu politics.

Whatever about the Brexit debate, was Berlin really so sanguine about positive liberty?

““This paradox has been often exposed. It is one thing to say that I know what is good for X, while he himself does not; and even to ignore his wishes for its – and his – sake; and a very different one to say that he has eo ipso chosen it, not indeed consciously, not as he seems in everyday life, but in his role as a rational self which his empirical self may not know – the ‘real’ self which discerns the good, and cannot help choosing it once it is revealed. This monstrous impersonation, which consists in equating what X would choose if he were something he is not, or at least not yet, with what X actually seeks and chooses, is at the heart of all political theories of self-realization. It is one thing to say that I may be coerced for my own good which I am too blind to see: this may, on occasion, be for my benefit; indeed it may enlarge the scope of my liberty. It is another to say that if it is my good, then I am not being coerced, for I have willed it, whether I know this or not, and am free (or ‘truly’ free) even while my poor earthly body and foolish mind bitterly reject it, and struggle against those who seek however benevolently to impose it, with the greatest desperation”.

Two Concepts of Freedom

Would not Rousseau make a better for the sort of freedom being advanced in this piece – that one is free if living under laws that one had some part in making/agreeing?

Just a thought