Halfway through the Brexit negotiations and delivering on the promises made to voters in the run up to the Brexit vote with regards to fishing remains an incredibly tough task. Richard Barnes, Chris Williams, Bryce Stewart, Bethan O’Leary, Thomas Appleby, and Griffin Carpenter write that ‘success’ will only be possible by working with our EU neighbours, and listening to both stakeholder groups and to the diverse actors within them.

After months of grandstanding over access to waters by UK and EU fishing chiefs, the realisation that the UK will require new fisheries policy post-Brexit seems to have finally set in. The Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee has initiated an evidence inquiry, and Defra are running a number of tenders to examine the current UK quota system, conditions on UK registered vessels to land or employ in Britain, and wider options for the future of UK fisheries. The Government’s Fisheries White Paper, precursor to the Fisheries Bill, is expected in early 2018.

Some important forays into fisheries have been made since the Brexit vote. The House of Lords Report set the scene, emphasising the importance of fishing to coastal communities, seafood trade, and cooperation in management. It called for a new legal baseline.

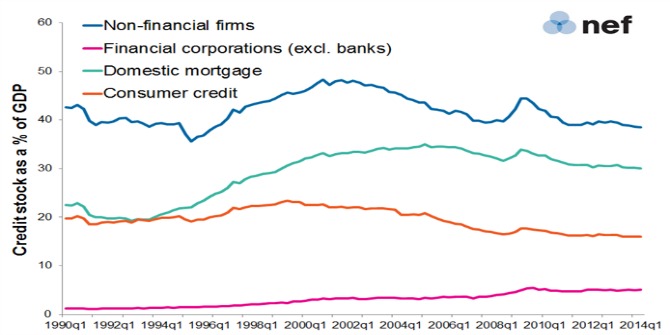

The potential gains in quota and landings based on the British 200 mile exclusive economic zone (EEZ) have been analysed in several studies, although a recent report from the New Economics Foundation calculates that the current distribution of quota holdings means that those gains are highly concentrated. Add the potential for tariff and non-tariff barriers, and half the fleet, which relies on EU exports, is looking at a more difficult future.

A report from the University of York analysed stakeholder priorities post-Brexit, drawing on a wide range of opinions. Encouragingly, all agreed that sustainability of fisheries should take top priority, however, other differences between groups emerged. While the fishing industry urged the need to increase the UK share of quotas and restrict foreign access to the British EEZ, NGOs and academics were more focussed on ensuring the protection of marine ecosystems. Meanwhile the priority of seafood processors (a larger industry than the catching sector) was to guarantee low or zero tariff trade and a viable workforce, given current reliance on non-UK EU workers.

Where there is common ground between different fisheries stakeholders, this must be secured and used to drive cooperation across the sector. Agreement already exists on three key issues, as evident from preliminary inquiries into fisheries. First, a no deal Brexit would be a disaster for UK fisheries. It would deliver a damaging, and in some cases crippling blow to the majority of fishers, and associated businesses, who send fish for export. Second, fisheries must be governed as an integrated part of the marine environment. This requires a focus on a greater number of impacts as well as a greater range of stakeholders. Third, any fisheries policy must secure a sustainable use of the resource. Without this everyone loses out.

Pixabay/Public Domain.

Pixabay/Public Domain.

Beyond these three key issues, there is general agreement that we need to develop a management regime that fits the natural, social, and economic conditions of UK fisheries. This entails more work on the following points:

Fish are a public resource

Fundamentally, fish are a public resource. This is reflected in the legal notion of the public right to fish, something that can be traced back to Magna Carta. Fisheries must be managed in the public interest – serving the needs of wider society, including future generations, and not just a select group stakeholders. This principle needs to be translated into action, with new or existing bodies strongly mandated to deliver it. This could have positive implications for questions of allocation, use and benefit. For example, it could be used to open the way for allocation of fishing rights linked to job creation, the delivery of social benefits, or conservation gains.

Creative thinking about sustainability

While the objectives for fisheries are diverse, sustainability must be centre stage. This is often pursued through regulations, but there are also market-based initiatives like the certification of sustainable products that can be leveraged to incentive best practices in fisheries. These schemes do not just have to be industry driven, but can be advanced by States (in partnership with industry).

Fisheries and environmental management must be ‘joined-up’

Integrating fisheries and environmental regulation would align two important and intrinsically linked areas of governance. This is important, especially given the need to better manage externalities from one sector impacting the other. One of the key failings of the Common Fisheries Policy was its failure to directly incorporate environmental legislation. There is some accommodation of environmental and fisheries in the Marine and Coastal Access Act. With exclusive responsibility for all fisheries and marine environmental matters returned to the UK, this Act will need to be reformed to account for additional and changed management responsibilities.

Of paramount importance will be aligning legislation and management properly between the UK Parliament and the devolved administrations. Fisheries and environmental management are currently devolved matters and it is not clear how the end of European competences in these areas will act on the UK constitutional settlement. This will require considerable internal diplomacy.

Any mechanism established to plan for and distribute fishing rights must recognise the need to only permit sustainable exploitation. It is debatable whether there is a need for a further environmental watchdog; it would be better for any administrative bodies to contain internal review process, with better access to judicial review.

Diversity in the sector

Fisheries law must protect and enhance diversity in the sector. The worry is that in its present form, some fleet types – typically small-scale fishing vessels – are particularly at risk. A better deal for inshore fishers (vessels under 10 metres) to ensure quota is not even further concentrated in fewer hands than it is currently.

It also means giving a voice to other sectors, such as recreational fishing. This reflects the public nature of the fishery and harnesses valuable stakeholder contributions.

Finally, it also means ensuring a degree of local autonomy in the management of local fisheries. This allows adaptation to local conditions and the accommodation of relevant environmental and social factors. This could be enhanced by expanding the remit and authority of Inshore Fisheries and Conservation Authorities to 12 nautical miles. This could also be a shrewd response to address some of perceived inequities of foreign fishing around the UK coast that drove the Brexit movement.

The thorny issue of shared stocks

The most difficult decisions will be those that involve shared fish stocks with the EU, of which the UK has many (many more than Iceland, Norway, or other coastal states). In the UK strong calls have been made to use zonal attachment, which grants fishing rights to each country in proportion to the country’s waters where the fish spend the most part of their life-cycle. The EU remains wedded to the principle of relative stability, which is based on historical fishing activity. Neither approach can claim to have legal or political priority.

Whilst relative stability is well-developed within EU law and practice, this will not be binding on the UK after Brexit. Zonal attachment is used in the EU Norway agreement, but would need to be developed for a much wider range of species in any EU-UK agreement. It is also highly vulnerable to changes in stock distribution from factors like climate change – something that has already effected the distribution of key species like cod. What establishing a new principle of zonal attachment would mean for devolved administrations seeking their ‘fair share’ must also be handled with care.

Ensuring the interests of the processing sector

The dependence of the processing sector on overseas markets means that fisheries cannot be viewed separately from wider trade issues. The UK is highly dependent upon the EU market and new markets will not simply spring into being after Brexit because of the start-up costs, logistics or uncertain trading regime. As a large portion of fish is sold fresh, the seafood industry is particularly prone to a ‘gravity model’ of trade.

Counting down and cooperation

We are now more than halfway through the countdown to Brexit. However, the task ahead to design a marine management regime that delivers sustainability, equity, and on the promises made to the electorate in the run up to the Brexit vote, remains an incredibly tough one. How to deliver a ‘successful’ UK fisheries and marine environmental policy under Brexit is uncertain. But what is known, is that ‘success’ will only be possible by working with our EU neighbours, listening not only to broad stakeholder groups but also to the diverse actors within them, and focussing on the end goal of sustainable, equitable, and integrated marine management.

_________

Richard Barnes is Professor at the Faculty of Business, Law and Politics, University of Hull.

Richard Barnes is Professor at the Faculty of Business, Law and Politics, University of Hull.

Chris Williams is Senior Programme Manager at the New Economics Foundation.

Chris Williams is Senior Programme Manager at the New Economics Foundation.

Bryce Beukers-Stewart is Lecturer at the University of York.

Bryce Beukers-Stewart is Lecturer at the University of York.

Bethan O’Leary is Research Associate at the University of York

Bethan O’Leary is Research Associate at the University of York

Thomas Appleby is Associate Professor in Property Law at the University of the West of England.

Thomas Appleby is Associate Professor in Property Law at the University of the West of England.

Griffin Carpenter is Senior Researcher at the New Economics Foundation.

Griffin Carpenter is Senior Researcher at the New Economics Foundation.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image: Pixabay/Public Domain.

Dave

It’s a good idea – but that is not what the Kiwi system does.

There’s a report which will shortly be published looking at the Kiwi system as a potential template. Be very careful what you wish on yourself.

http://www.bluemarinefoundation.com/2017/11/23/11040/

Tom

I feel this article still pays no more than lip service to the public right of access to the fishery, and the economic potential of recreational angling. The NZ approach, where commercial exploitation is only allowed once the public recreational demand has been fulfilled, is more reasonable