A major argument of the Leave campaign is that Brexit would give the UK more control over the flow of EU immigrants, who have supposedly hurt the jobs and pay of British workers. Research by Jonathan Wadsworth, Swati Dhingra, Gianmarco Ottaviano and John van Reenen shows that far from EU immigration being a ‘necessary evil’ of being in the EU Single Market, immigration is at worst neutral and at best, an economic benefit of EU membership.

A major argument of the Leave campaign is that Brexit would give the UK more control over the flow of EU immigrants, who have supposedly hurt the jobs and pay of British workers. Research by Jonathan Wadsworth, Swati Dhingra, Gianmarco Ottaviano and John van Reenen shows that far from EU immigration being a ‘necessary evil’ of being in the EU Single Market, immigration is at worst neutral and at best, an economic benefit of EU membership.

Many Britons are concerned that high levels of immigration have hurt their jobs, wages and quality of life. This anxiety is understandable as workers have had a rough ride in recent times. Allowing for inflation, average wages fell by 8 per cent to 1 per cent in the six years after the global financial crisis of 2008. Such a sustained fall in pay is unprecedented in British post-war history.

Alongside falling wages, immigration from the EU has been soaring. Between 1995 and 2015, the share of EU nationals in the working age population more than tripled from 1.8 per cent to 6.3 per cent, and most of this happened after 2004 when eight East European countries joined the EU. Net EU immigration flows were about 172,000 in 2015, not far off the non-EU rate of 191,000. So it does make sense that many people believe this immigration wave has hurt UK workers and think that leaving the EU would make things better.

To investigate this we crunched the most recent data and scoured the evidence. The bottom line is that EU immigration has not significantly harmed the pay, jobs or public services enjoyed by Britons. In fact, for the most part it has made us better off. Far from EU immigration being a ‘necessary evil’ that we must bear in order to gain access to the greater trade and foreign investment generated by the EU Single Market, immigration is at worst neutral and at best another economic benefit of membership.

EU immigrants and their impact on the UK labour market

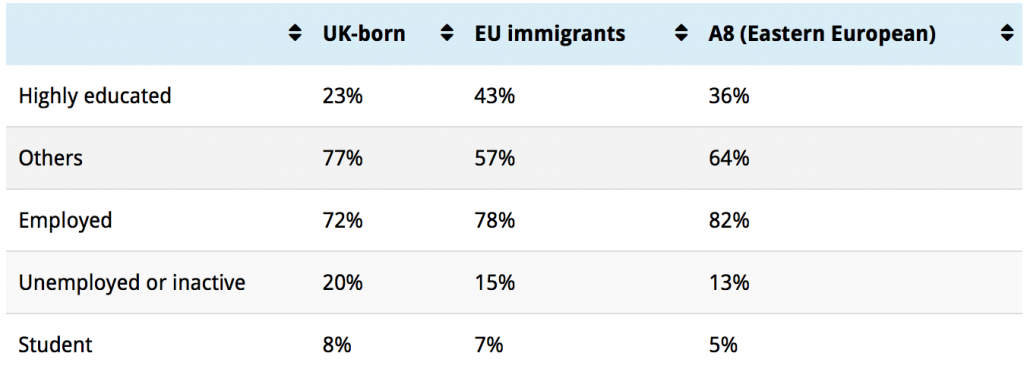

Immigrants from the EU are younger and more educated than the UK-born – for example, almost twice as many have received some form of higher education. They are also more likely to be in work, especially those entering from Eastern Europe.

Notes: Labour Force Survey data from 2015. ‘Highly educated’ are people who were in education until the age of 21 or older. ‘A8’ Eastern and central European countries are the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia who joined the EU in 2004. Working Age population is everyone over the age of 16 and under the age of 65.

Having young, well-educated and hard-working people coming to your country might not seem such a bad thing. But since immigration increases competition for jobs, doesn’t it mean that the employment prospects for UK workers have got worse? After all, there are always stories of someone who has gone after a job but has missed out to an immigrant.

But higher immigration does not mean that UK unemployment must always rise as a result because there isn’t a fixed ‘lump of labour’ out there. Immigrants have to eat, drink and live somewhere. They spend money on local goods and services. All this pumps up demand creating new jobs. Adding an immigrant is like increasing population and the population of the UK has risen by around a half over the last hundred years, but the unemployment rate has not marched forever upward.

Yet even if there is no reason to think that immigration should increase unemployment, isn’t it obvious that a bigger supply of workers must increase competition for jobs and drive wages down? Again – it isn’t necessarily so.

Greater movement of labour allows countries to specialise in what they are best at, just like being more open to trade. Companies change the mix of services and products to adapt to the new skills available to them. Immigrants – especially if they are more skilled – will tend to raise productivity. Demand for services means more demand for people to supply them. All these effects will tend to raise real wages. So ultimately we cannot know the truth about immigration and its effects from just appealing to anecdotes or theories. We need to look at the evidence.

Luckily, there is a huge amount of research examining the effect of immigration on jobs and wages. The conclusion of this body of work is that the large increase in immigration did not significantly harm the job and wage prospects of British workers. But most of this research was done on data in the good times before the global financial crisis and the Eurozone crisis. Have things changed since 2008 when the job market got tougher?

If we look at employment rates of the UK-born over the last four decades since the last EU referendum, there is little relationship with EU immigration. Although EU immigration rose during 2008-10 when employment rates fell, immigration also rose in the last five years when employment rates recovered. Similarly, although wage rates were falling in the period 2008-14 when immigration was rising, wages were still going up in the period 2004-08 as well as in the last year. The problem of falling wages was due to the financial crisis and austerity – not to immigration.

What about at the local level? Did places with larger influxes of EU immigrants have worse job outcomes than those with smaller increases? Our latest research finds that in fact there is no relationship between EU immigration and the unemployment rates or wages of those born in the UK.

But what about impacts on certain types of workers? After all, there is concern that less skilled workers are hurt if educated immigrants are willing to accept low paying jobs. To see if prospects for less skilled UK nationals are associated with EU immigration, we looked at the changes in pay and job rates of the low educated. Our results are unchanged: EU immigration has not harmed local British workers.

Public finances and public services

Since EU immigrants are younger, more likely to work, and better educated they also pay more in taxes than they receive in welfare payments. For example, A8 Eastern European immigrants paid in about £15 billion more than they took out in public spending and benefits in the decade up to 2011 (while UK nationals received more than they put in over the same period).

So EU immigrants are helping to reduce the budget deficit which helps pay for more public services for the British born population. They bring in extra assets that could be used to increase spending on the NHS and education for the UK-born.

Although the fact that the government has been cutting back on public services cannot be blamed on immigrants, it could still be that local areas which saw bigger immigrant inflows experienced worse services. But the evidence suggests that there is no significant effect on education and the NHS or social housing. If immigrants led to social conflict then we would expect to see this reflected in measures of crime rates. But again, there is no discernible effect.

Immigration and productivity

A disadvantage of focusing on outcomes in local areas is that it may miss out on the economy-wide effects of immigration. By enabling specialisation and raising productivity, immigration can raise national wages through boosting productivity. Migration acts much like international trade, as people tend to move to countries where they can be more productive and earn higher incomes. Immigrants tend to be the most entrepreneurial and talented people.

Many studies find positive effects of immigration on productivity, especially when immigrants are more educated. Recent work by the OECD finds that halving UK net immigration rates would reduce UK productivity growth by 0.32 per cent per year. Since average UK productivity growth has been almost flat as a pancake since the financial crisis, this is not something to be lightly discarded.

Brexit supporters argue that economic benefits would flow from bringing EU immigration under the same rules as non-EU immigrants. The OECD study also looks at how improving the average skill level of immigrants could increase productivity. To offset the productivity loss from halving EU net immigration, the UK immigration system would have to enormously improve the relative education level of EU immigrants. Since EU immigrants are already significantly better educated than the UK-born this would be an extremely difficult task to pull off, especially with an aspiration to cut total net immigration to the tens of thousands.

Refugees

The refugee crisis is not related to the UK’s membership of the EU. Refugees given the right to remain in other EU countries like Germany have no right to live or work in the UK. It usually takes between five and eight years before refugees are even allowed to apply for citizenship. The UK is not in the Schengen passport-free travel agreement, so there are border checks preventing entry of refugees.

The bottom line

We can confidently say that the empirical evidence shows that EU immigration has not had significantly negative effects on average employment, wages or inequality for British people. At the national level, falls in EU immigration would be likely to lead to lower British incomes. This is partly because immigrants are more likely to be in work (helping reduce the deficit) and partly because they have a positive influence on productivity.

There is a wide consensus that trade and foreign investment will fall after Brexit, which will hurt UK living standards. Cutting EU immigration will not offset these costs. Indeed, it is likely to make British incomes even lower.

___

Note: The above is based on the CEP’s fifth briefing paper on the effects of leaving the EU. It was first published on LSE Business Review and Brexitvote.

Jonathan Wadsworth is a senior research fellow at LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance (CEP). He was a member of the Home Office’s Migration Advisory Committee 2007 to 2015. Email: j.wadsworth@lse.ac.uk

Jonathan Wadsworth is a senior research fellow at LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance (CEP). He was a member of the Home Office’s Migration Advisory Committee 2007 to 2015. Email: j.wadsworth@lse.ac.uk

Swati Dhingra is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Economics at LSE. Her research interests are international economics, globalisation and industrial policy. Her work has been published in top economic journals including The American Economic Review.

Swati Dhingra is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Economics at LSE. Her research interests are international economics, globalisation and industrial policy. Her work has been published in top economic journals including The American Economic Review.

Gianmarco Ottaviano is Professor of Economics at LSE and an associate at LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance Trade Research Programme. His research interests include international trade, multinationals, economic integration, immigration and economic geography. He holds a PhD in Economics from the Catholic University of Louvain, Belgium.

Gianmarco Ottaviano is Professor of Economics at LSE and an associate at LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance Trade Research Programme. His research interests include international trade, multinationals, economic integration, immigration and economic geography. He holds a PhD in Economics from the Catholic University of Louvain, Belgium.

John Van Reenen is a Professor in the Department of Economics and Director of LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance.

John Van Reenen is a Professor in the Department of Economics and Director of LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance.

Yesterday, Former Work and Pensions Secretary Iain Duncan Smith who was at the heart of employment figures and must have known all the facts from his experience in that department, said the very opposite of what has been quoted in this article.

So there is plenty of room for doubt as to the findings of this report.