The political economic transformation of Britain has resulted in many individuals ‘winning’ through social mobility and others ‘missing out’. However, the effect of these gains and losses has not been assessed regarding voters’ position in the Brexit vote. Andrew McNeil and Charlotte Haberstroh show that the Brexit cleavage is influenced by both an individual’s social origin and destination position.

The political economic transformation of Britain has resulted in many individuals ‘winning’ through social mobility and others ‘missing out’. However, the effect of these gains and losses has not been assessed regarding voters’ position in the Brexit vote. Andrew McNeil and Charlotte Haberstroh show that the Brexit cleavage is influenced by both an individual’s social origin and destination position.

Over the last half century, the political economy of Britain has been transformed by the linked processes of skill-biased technological change, occupational upgrading, and educational expansion. These abstract macro structural changes had life changing consequences for individuals. For many, the result was a higher socio-economic position than their parents: a higher status job, going to university, or both. However, we also know that rates of absolute downward social mobility have increased, and many individuals remain in the same low socio-economic position as their parents.

At the same time, a consensus has developed that those individuals who ‘lost out’ to their peers were the cornerstones of the ‘Leave’ Brexit vote, and more generally of anti-system movements across Europe. Defining those who ‘lost out’ or the ‘left-behind’ is methodologically challenging and, at best, remains a fuzzy concept. Potential explanations include individual-level measures such as educational attainment, occupation, and subjective social status. Similarly, voters may be nested in regions which have been ‘left behind’ through globalisation, austerity, or relatively low house prices. We argue that one’s own experience of intergenerational social mobility chimes with this explanation, and, in fact, how one has fared compared to one’s parents is the clearest reference point for ‘winning’ or ‘losing’ in the face of political economic change.

This absence of intergenerational social mobility from the anti-system debate is even more surprising given we know its importance for a wide range of outcomes. These include voting on the left-right spectrum, redistributive attitudes, and political distrust. Away from political variables, social mobility matters for behaviours as diverse as personal well-being to smoking.

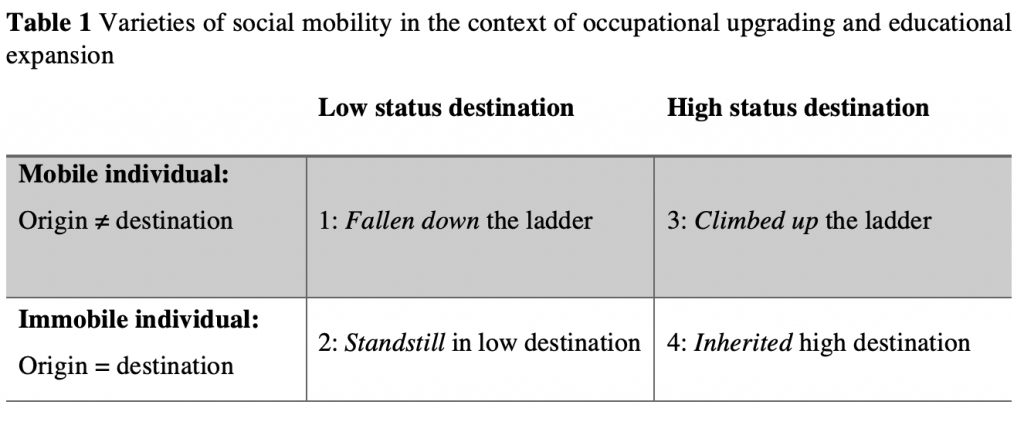

We identify how the positions of intergenerationally mobile voters in the Brexit referendum differ from those of their non-mobile counterparts. We therefore propose a second dimension to socio-economic position, differentiating between mobile and immobile individuals. In its simplest form, we conceptualise four stylised groups (Table 1). Those with a low socio-economic position may have the same position as their parents (‘Standstill in low destination’) or, alternatively, have been downwardly mobile (‘Fallen down the ladder’). Similarly, those in a high socio-economic position may have inherited this position from their parents (‘Inherited high destination’) or experienced upward mobility (‘Climbed up the ladder’).

When comparing the socially mobile to their immobile peers, theoretically they may (1) relate to those immobile individuals in their destination position; (2) relate to the immobile individuals in their origin position; or (3) the experience of mobility itself could have an effect. Our empirical strategy uses a methodology which allows us to disaggregate these effects.

Social origins. Adulthood political attitudes and ideologies may be shaped through childhood experiences, including networks of families and friends, education, and neighbourhoods. To take our ‘Climbed up the ladder’ group from Table 1, it may be that these individuals are likely to vote ‘Remain’ as they strongly identify as ‘winners’ with their new high status socio-economic position. Alternatively, they may identify with a combination of the immobile group from their origin (those in ‘Standstill’) and the immobile group in their destination position. This same logic applies to those who have ‘Fallen down the ladder’.

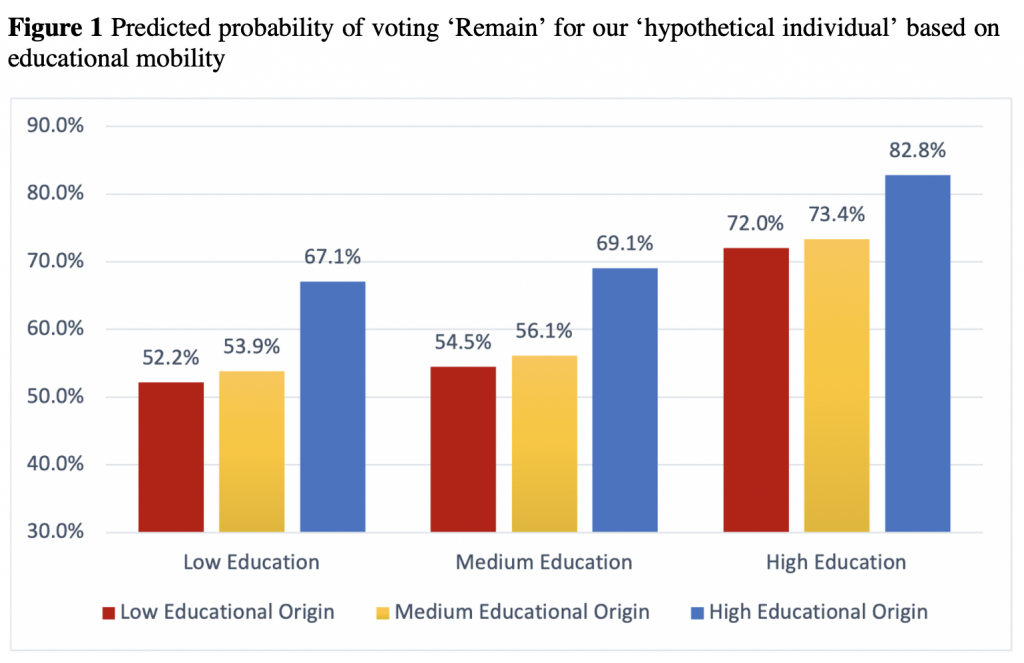

Using data from Understanding Society, we find, unsurprisingly, that there is a clear gradient in voting behaviour for Brexit by immobile groups. Those individuals who inherited a high socio-economic position from their parents are most likely to vote ‘Remain’, whereas individuals who stayed in a low socio-economic position like their parents are least likely to vote ‘Remain’. However, crucially, our analysis shows that there is a statistically significant and substantial weighting to one’s origins. Whether measured by educational attainment or occupational class, social origin is nearly as influential as one’s destination position for the tendency to vote ‘Remain’.

Mobility effect. Over and above origin and destination effects, the act of moving from one socio-economic position to another may affect one’s position in the Brexit divide. However, theoretically the direction of this effect is unclear. It may be that the upwardly mobile associate their success with the current state of society, and thus are more likely to vote to ‘Remain’, maintaining the status quo. Conversely, the downwardly mobile may blame their situation on an unfair society, therefore increasing the tendency to vote for a change, ‘Leave’. An alternative hypothesis is that both upward and downward mobility increases one’s tendency to vote ‘Leave’, mobile individuals are not fully integrated into either their social origin or destination position.

In our main analysis, we do not find any statistically significant effect of social mobility, over and above origin and destination effects. In robustness tests, we find some weak evidence that there may be a small upward mobility effect, making one more likely to vote ‘Remain’ – albeit this would be much smaller than the origin and destination effects.

To clarify our understanding of the differences of individuals according to social origin and destination, we created a hypothetical individual, choosing values for each of our controls, and plotted predicted probabilities based on educational social mobility. If an individual reached their high educational position through upward mobility, they are 10 percentage points less likely to vote ‘Remain’ than their immobile peers. The group least likely to vote ‘Remain’ are those who have been ‘left-behind’ over multiple generations, attaining a low educational position in-line with their parents.

After an extended period of political economic transformation, many individuals have been socially mobile. Individuals who ‘reached’ or ‘fell’ to their socio-economic destination position remain different to their immobile peers. Social origins still matter. To take a group widely perceived as homogenous, graduates, first generation graduates are much more likely to vote ‘Leave’ than their immobile peers. Political identities, measured here by Brexit, are inherently complicated, reaching beyond traditional measures of socio-economic position. Thus, creating cross-group political coalitions increasingly challenging, and politics more unstable.

Our findings resonate with other literature analysing individual’s social mobility, and the proximate field of intra-generational mobility. Whilst we do not discount that ‘loss‘ is an important part of one’s identity, our findings suggest that socialisation dominates these effects. In follow up work, we analyse the generalisability of these results to anti-system voting across Europe. Social mobility matters across Europe for the anti-system right, but not the anti-system left. Individuals’ social mobility is an underappreciated variable for understanding the new cleavage structure of British politics, and beyond.

______________________

Note: the above draws on the authors’ published work in the European Journal of Political Research.

Andrew McNeil is a PhD candidate in the Department of Government at LSE.

Andrew McNeil is a PhD candidate in the Department of Government at LSE.

Charlotte Haberstroh is Visiting Fellow in the Department of Government at LSE.

Charlotte Haberstroh is Visiting Fellow in the Department of Government at LSE.