There is extensive literature mapping the decline of religiosity in the UK, yet this does not mean that religion is disappearing entirely. Sarah Wilkins-Laflamme explains that there is a substantial minority still actively involved with religion. The religiously committed also have more favourable views towards religious leaders influencing politics than they did previously, while the unaffiliated now have less favourable views towards public religion.

There is extensive literature mapping the decline of religiosity in the UK, yet this does not mean that religion is disappearing entirely. Sarah Wilkins-Laflamme explains that there is a substantial minority still actively involved with religion. The religiously committed also have more favourable views towards religious leaders influencing politics than they did previously, while the unaffiliated now have less favourable views towards public religion.

The now century-old decline of religiosity in England, Scotland and Wales is often measured by indicators such as church worship, denominational identity and membership as well as Sunday school attendance. Grace Davie caused quite a stir when she proposed that more individually-constructed belief systems and spiritualities may persist among large chunks of the British and European populations, despite the decline of organized religion. Academic battle ensued: secularization researchers took it upon themselves to show that beliefs too were waning in Britain and across Europe, although usually more slowly and as a later stage of the decline process.

Does this mean that religion is disappearing entirely from Great Britain in its advanced stage of secularization? In short, no. According to recent waves of the British Social Attitudes survey (BSA), an estimated 48 per cent of the population is religiously unaffiliated (2012); 36 per cent does not believe in God (2008); and 66 per cent never attends religious services (2012). Most among this non-religious population are also raising their kids with no real contact with religion.

Yet, there is a substantial minority of people still actively involved with religion. The proportion of individuals who identify with a religious group and say they attend religious services at least once a month has stayed relatively stable around the 17 per cent mark since the year 2000, and around the 14 per cent mark among those born after 1960. The outflow of those letting go of their regular religious practice in the more secular context of Great Britain seems to be currently compensated by an influx of regular attenders coming from more religious areas of the world. So although the dynamics of the religious landscape are shifting, the religiously active are still very much a part of society.

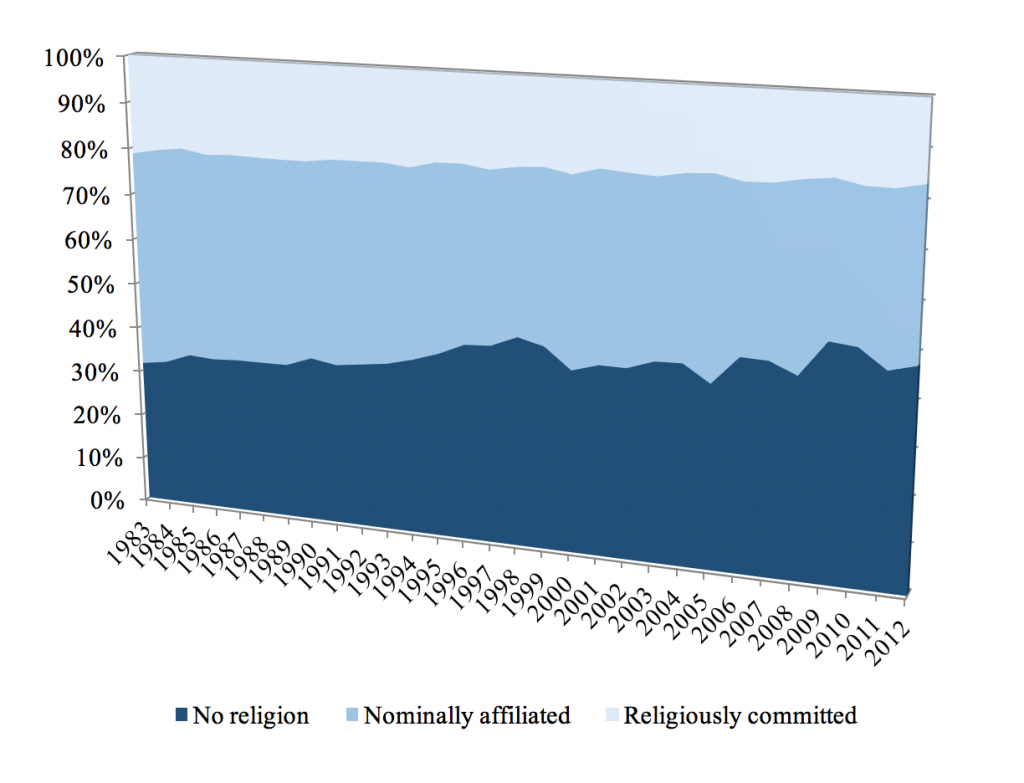

Figure 1: Proportion of religiously committed (affiliated and attend religious services at least once a month), nominally affiliated (affiliated and attend religious services less than once a month) and unaffiliated respondents, by year (1983–2012), weighted, Great Britain

Notes: 1983-2012 BSA data. Cited from Wilkins-Laflamme.

Notes: 1983-2012 BSA data. Cited from Wilkins-Laflamme.

Consequently, Britain finds itself in an era when, in the words of Charles Taylor, belief and non-belief coexist. On the one hand, the unaffiliated as a whole assign little importance to organized religion in their lives and are generally much more liberal in their views. The religiously active, on the other hand, share a fundamental belief about the importance of faith, of the supernatural, and of the religious community in everyday life. And the gap in terms of attitudes and behaviour may be widening between the two groups. My research shows that there is a greater distance between the actively religious and the unaffiliated in recent years in terms of their religious/spiritual beliefs and their attitudes towards public religion. Based on multivariate regression models run with data from the 1991, 1998 and 2008 BSAs, I find that the actively religious group as a whole generally has stronger beliefs and more favourable views towards religious leaders influencing politics in 2008 than in 1991, while the unaffiliated have less favourable views towards public religion.

This greater divide in the British (non)religious landscape could have a significant impact in other social spheres. Actions and policies from one side may leave the other feeling targeted and alienated. A non-religious majority assuming that religion is no longer an issue may be taken aback when an active, sometimes visible and vocal, minority pushes back. Since religion and religiosity are known to have a strong influence on values and political choices in Western democracies, a significant divide in the (non)religious landscape could extend to the political one. It also has the potential to extend to other social domains which religion is known to affect, such as physical and mental health, volunteering, family formation and educational track.

Somewhat counter-intuitively to classic secularization models, controversies surrounding religion and the importance of level of religiosity in predicting attitudes and behaviour may become greater in areas of advanced secularization, not weaker. I am not saying a religious/secular Culture War has begun or is even imminent in Britain, but I am arguing that it’s worth paying attention to the complexities involved in this new religious context in order to avoid such an outcome.

___

Note: the article draws on the author’s published work in The British Journal of Sociology.

Sarah Wilkins-Laflamme is an Assistant Professor at the University of Waterloo in Canada. She completed her DPhil in sociology at Nuffield College, University of Oxford (2010-2015). Her research interests include the sociology of religion, quantitative methods, social change, race, ethnicity and immigration.

Sarah Wilkins-Laflamme is an Assistant Professor at the University of Waterloo in Canada. She completed her DPhil in sociology at Nuffield College, University of Oxford (2010-2015). Her research interests include the sociology of religion, quantitative methods, social change, race, ethnicity and immigration.

For an example of how these trends are dramatised and played out, in the light of secularisation theories and Charles Taylor’s work, see my doctoral thesis on the practices of British Quakers: ‘The Place that Words Come from…” An Ethnographic Study of The worship Practices of Quakers and their Social Enactment’ University of St Andrews 2011, now unembargoed and available on-line.

Hello Dr Lloyd-Richards, I don’t know if you will be notified of this comment. I am very interested in the work you did with LINK/GAMH in the 1970s and 80s and was wondering if you’d be willing to discuss further? Would you be willing to contact me with your email address? My email is m.gallagher.3@research.gla.ac.uk