When Jeremy Corbyn was elected Labour leader in 2015, the result astonished many; his re-election surprised no-one. Analysing the 2016 voting data, Peter Dorey and Andrew Denham find a few surprises amidst the details.

When Jeremy Corbyn was elected Labour leader in 2015, the result astonished many; his re-election surprised no-one. Analysing the 2016 voting data, Peter Dorey and Andrew Denham find a few surprises amidst the details.

In Labour’s 2015 leadership contest, a major question had been how a rank outsider and perceived political maverick, like Jeremy Corbyn, could possibly be elected leader of a Party in which he enjoyed very little support among its MPs, and in which he had never held even the most junior Ministerial office. In the 2016 leadership contest, the main question was no longer whether or how Corbyn could win, but by what margin.

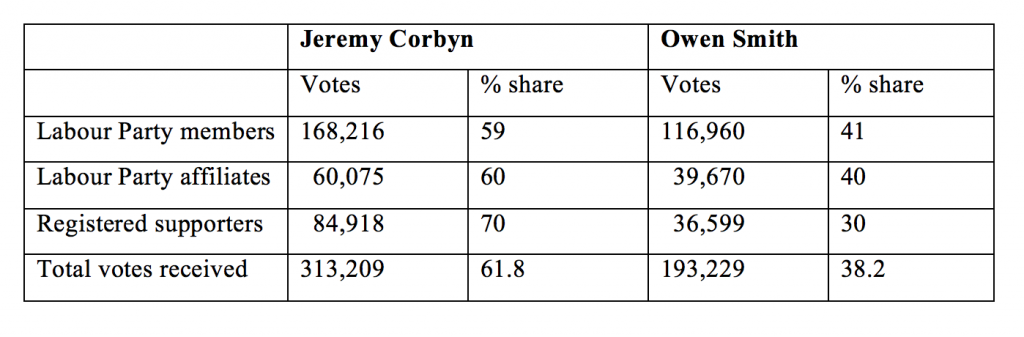

In the event, Corbyn’s won another strong victory (Table 1), which also shows that he enjoyed a clear lead among all three categories. His total support increased slightly, up from 59.5 to 61.8 per cent.

Table 1: Labour leadership election result 2016

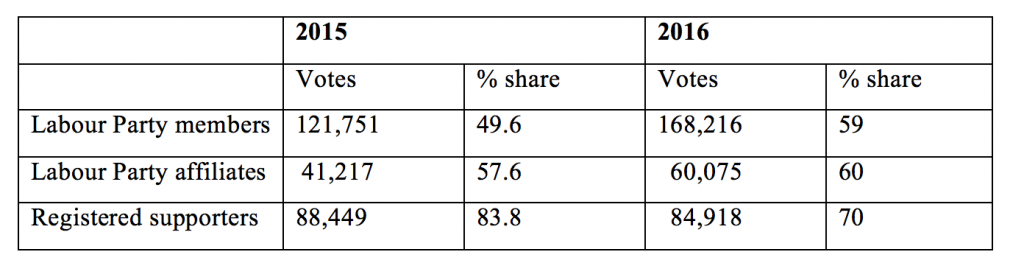

However, these figures belie some subtle changes in the scale and sources of Corbyn’s support since 2015, as revealed by Table 2.

However, these figures belie some subtle changes in the scale and sources of Corbyn’s support since 2015, as revealed by Table 2.

Table 2: Changes in Corbyn’s support compared to 2015, by voter category

Corbyn’s support increased both among fully-paid up Labour Party members, and those who belong to affiliated organisations (most notably trade unions), but declined among ‘registered supporters’, from nearly 84 per cent in 2015 to 70 per cent a year later. Yet the diminution of Corbyn’s support among this previously crucial category of voter reflects the fact that many of those who were ‘registered supporters’ in 2015 subsequently became fully-paid up members of the Labour Party, doubtless inspired to join precisely because of Corbyn’s 2015 election.

Corbyn’s support increased both among fully-paid up Labour Party members, and those who belong to affiliated organisations (most notably trade unions), but declined among ‘registered supporters’, from nearly 84 per cent in 2015 to 70 per cent a year later. Yet the diminution of Corbyn’s support among this previously crucial category of voter reflects the fact that many of those who were ‘registered supporters’ in 2015 subsequently became fully-paid up members of the Labour Party, doubtless inspired to join precisely because of Corbyn’s 2015 election.

It is also likely that a further impetus for some Corbynites to join as fully paid Party members was the July 2016 announcement that the ‘registered supporter’ fee – entitling subscribers to vote in Labour leadership elections – would be raised to £25 (from £3). Given that Labour’s standard membership fee is £47 per year, it is likely that many erstwhile or would-be ‘registered supporters’ decided to pay an additional £22 to upgrade to full-membership, particularly as this fee can be paid on a monthly basis. Thus did the number of fully-paid up Labour Party members increase from 245,520 in summer 2015 to 338,000 a year later.

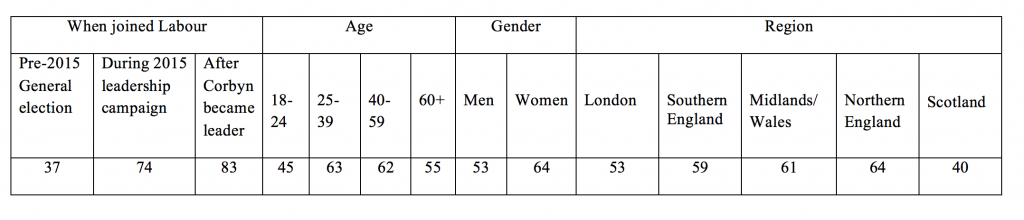

Even closer perusal of the 2016 result gleans some interesting similarities to the voting patterns of 2015, but also some surprising differences, in the support enjoyed by Corbyn among Labour Party members, as is apparent in Table 3.

Table 3: Social profile of Corbyn’s support among Party members (% of each category voting for Corbyn).

Source: YouGov ‘Exit’ poll, 21-23 September 2016.

Source: YouGov ‘Exit’ poll, 21-23 September 2016.

This shows the extent to which Corbyn’s support continued to be drawn heavily from more recent and younger Party members. Certainly, as in 2015, the more recently someone had joined the Labour Party, the more likely they were to vote for Corbyn: 83 per cent of those who had joined the Labour Party after Corbyn’s 2015 win voted for him in 2016, compared to only 37 per cent of those who had been full members before the 2015 general election.

As was also the case in 2015, Corbyn’s support in the 2016 leadership contest was rather stronger (62.5 per cent average) among those in their 30s, 40s and 50s, but falling back to 55 per cent among those aged 60+. One surprise, however, is that Corbyn’s support among the 18-24 age cohort in the Party was 10 points lower than Owen Smith’s (45-55 per cent), which rather undermines the common assumption that Corbyn was strongly attracting the youth vote. This might have been partly attributable to Smith’s call for a second referendum on Britain’s membership of the EU, with younger voters having been strong supporters of ‘Remain’, whereas Corbyn was widely viewed as lukewarm.

It is also notable that Corbyn’s support among Labour Party members in London was not as high as that which he attracted in the Midlands, the North of England and Wales. True, 53 per cent of London Party members voted for Corbyn, but this was clearly lower than his 64 per cent support among members in the North. Such figures suggest that we should treat with great caution the common assumption that Corbyn’s bedrock support derives from London’s cosmopolitan middle-class urban Left, the Camdenistas and Islingtonites tucking into organic nut-roast and quaffing Fair Trade Merlot, rather than from other parts of England where Labour urgently needs to regain support, particularly among working class voters. The biggest ‘defeat’ for Corbyn was in Scotland, where only 40 per cent of members voted for him.

It is, perhaps, significant that both London and Scotland were also strong supporters of ‘Remain’ in the recent EU referendum, and this might have curbed some support for Corbyn in these two areas. Meanwhile, Corbyn again proved notably popular among Labour’s female members, with 64 per cent of them supporting him in 2016, compared to 53 per cent of the Party’s men.

The headline figures therefore suggest that Jeremy Corbyn secured an emphatic and entirely predictable victory in the Labour Party’s 2016 leadership contest. In terms of the overall vote, his victory was indeed decisive, and slightly higher than in 2015. However, more careful analysis of some of the voting data reveals a more nuanced pattern, with Labour’s youngest Party members, and those living in London, somewhat less emphatically Corbynite than has been assumed, and with a majority of Scottish Labour Party members preferring Owen Smith.

Yet these caveats notwithstanding, Corbyn’s overall victory means that the Labour Party continues to be led by someone whose popularity among the extra-parliamentary membership is very much higher than it is among the Party’s MPs, many of whom will now be contemplating whether to stay in the PLP and continue opposing Corbyn, or leave and form a new political party – just as Labour’s ‘social democrats’ did in March 1981, following a decisive shift to the Left: fight or flight. The odds on the latter must surely have shortened considerably since Corbyn’s re-election?

____

Peter Dorey is Professor of British Politics at Cardiff University. For a full list of publications see here.

Peter Dorey is Professor of British Politics at Cardiff University. For a full list of publications see here.

Andrew Denham is Reader in Government at Nottingham University. For a full list of publications see here.

Andrew Denham is Reader in Government at Nottingham University. For a full list of publications see here.

Speaking as a Labour member in Wales, the frustrating thing about these numbers is the aggregation of the Midlands and Wales. Obviously Wales – with its devolved Government and Labour in office – has a distinctive political culture of its own, As someone who took part in Owen Smith’s campaign (but trying to be as objective as possible) my impression is that Smith was doing much better than those figures suggest – especially among long-standing, older Labour members; the fact that he is from Wales clearly mattered, and Corbyn was seen by many as the London candidate. I’d be fascinated to know if it was possible to get a snapshot of Wales without our being appended to the Midlands, with whom we have little in common politically, economically or culturally.

But maybe he has the support from the grassroots and it counts.

Surely what counts is the support of the electorate? And he hasn’t got that, has he?

The YouGov sample size for table 3 is 1019 people (how this sample was drawn is not set out on the YouGov site). This means that you are drawing conclusions about the sub groups from very small samples.For Scotland, it is an unweighted sample just 53 people and for and for 18 to 24 year olds 55 people – far, far too small to draw any conclusions whatsoever.

Is there similar data about the regional breakdown of the vote for last year’s leadership election? Would probably make for an interesting comparison, which might also help tease out more of an impression about the impact of the intra-Labour debate about the Brexit referendum.

In Scotland, methinks that many social democrats will have abandoned Labour to join SNP, leaving behind red-tie Tory Blairites.

Interesting to compare and contrast: Scottish Labour never give out the actual poll figures, only percentages. Are they worried about releasing their membership statistics?