Anna Zamberlan, Filippo Gioachin, and Davide Gritti show that both men and women who lost paid hours during the first lockdown increased the time they spent on domestic chores. They explain why this has nevertheless not led to a significant rebalancing of housework obligations.

Anna Zamberlan, Filippo Gioachin, and Davide Gritti show that both men and women who lost paid hours during the first lockdown increased the time they spent on domestic chores. They explain why this has nevertheless not led to a significant rebalancing of housework obligations.

Among their several societal implications, lockdowns have marked substantial employment changes, with rising unemployment and widespread reduction in working hours. The labour market shock was particularly strong during the first lockdown, which was sudden and largely unpredictable. According to the official figures, in April almost 30% of the entire UK workforce was furloughed, 50% moved to home working and about a million people claimed Universal Credit and Jobseeker’s Allowance. From 23 March and throughout April 2020, working outside the home was permitted only for ‘key workers’. Social distancing, ‘stay-at-home’ messages, and connected closures of public places and non-essential shops inevitably affected working arrangements and daily lives. What have been the consequences for intra-couple dynamics? How did male and female partners re-allocate their time in housework and childcare obligations?

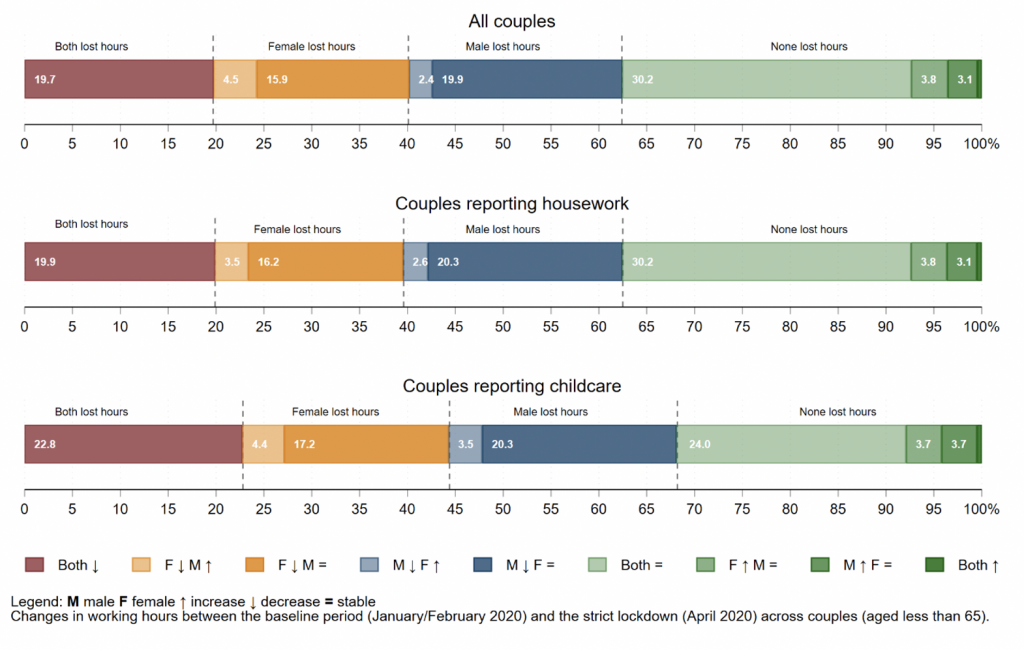

Making use of the UK Household Longitudinal Study and the Understanding Society COVID-19 study, we investigated the distribution of working hours loss occurred from January/February 2020 to April 2020. Figure 1 shows who, among heterosexual partners, lost working hours during this time. No relevant differences can be detected between childless couples and couples with children. Overall, in almost 20% of the couples both partners lost working hours. In addition, it was slightly more common for men to be the ones losing working hours compared to women.

Figure 1 – Percentage distribution of changes in paid hours across couples during first COVID-19 lockdown.

The generalized loss of working hours, especially for men, could be expected to have led to a revision of the traditional division of labour among partners. Despite the growth in women’s labour force participation in recent decades, the way domestic tasks have been allocated between genders has proved resistant: housework and childcare still appear to be female responsibilities. This is the case in the UK too, which is generally described as a ‘modified male breadwinner’ society. In this context, we can still observe a traditional gendered division of domestic work despite women’s large-scale participation in the labour market.

The generalized loss of working hours, especially for men, could be expected to have led to a revision of the traditional division of labour among partners. Despite the growth in women’s labour force participation in recent decades, the way domestic tasks have been allocated between genders has proved resistant: housework and childcare still appear to be female responsibilities. This is the case in the UK too, which is generally described as a ‘modified male breadwinner’ society. In this context, we can still observe a traditional gendered division of domestic work despite women’s large-scale participation in the labour market.

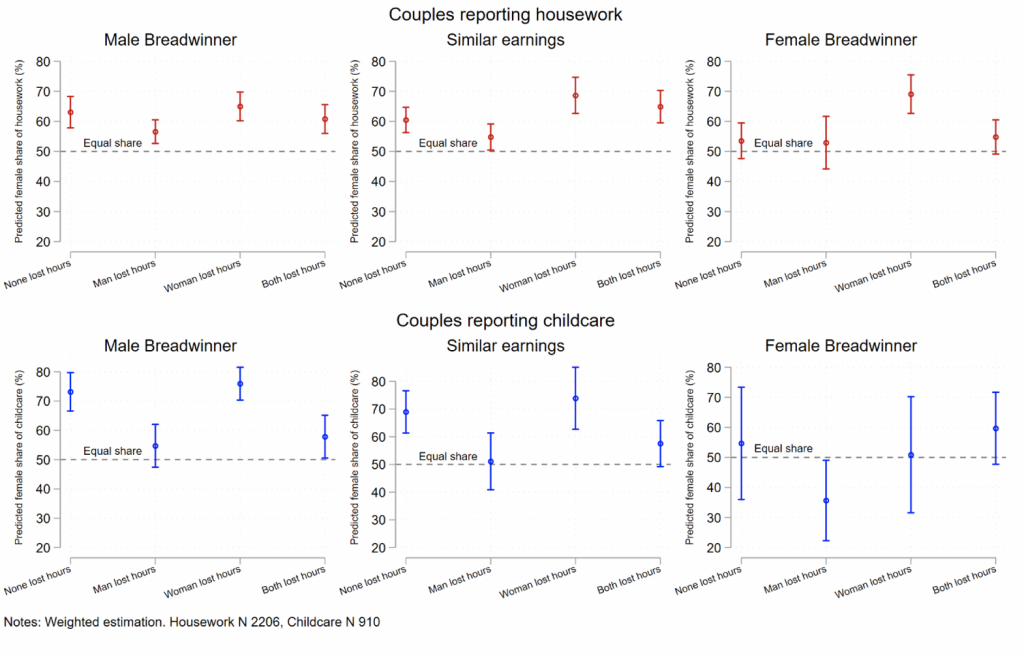

Nevertheless, not all families are the same. Households where one partner is the main earner and households where both earn similar amounts differ significantly in many aspects, including in the division of paid and unpaid labour. How have these different households reacted to the sudden loss of working hours Figure 2 shows the percentage of the total housework (top panels) and childcare (bottom panels) hours predicted to be performed by the female partner in households where the main earner is the man (left), the woman (right), and where the labour income in equal between the two (centre). ‘Breadwinner’ men who lost paid hours during the lockdown appear to have become more involved in childcare, thus approaching equality more closely. However, they did not significantly increase their housework time. Contrarily, female ‘chief breadwinners’ who lost paid hours reported a much higher marginal change in housework time than women who lost hours in the other types of family considered. Furthermore, in virtually all scenarios the woman contributed the greater share of domestic labour, regardless of her status in the couple.

Figure 2 – Predicted female share of housework and childcare in April 2020, based on which partner was the chief breadwinner, conditional on labour market changes (if any) during first lockdown. Percentage values. 95% confidence intervals.

These empirical results indicate that both men and women who lost paid hours increased the time devoted to domestic chores, but gender inequality struck back, especially after breadwinner women lost paid hours.

Gender disparities in the division of domestic tasks and their persistence mirror inequalities between men and women in other aspects of personal and social lives, among which the labour market stands out. The generalized loss of working hours due to lockdown has not led to a significant rebalancing of time spent within the house. This could be indicative of the strength of stereotypical gender roles, even when more equality would coincide with more efficiency (e.g. women being both the breadwinners and the ones responsible for household duties is inefficient).

How is it possible to erode traditional gender roles? In order for childcare to be more equally shared among parents, family policies (especially paternal leave) and the provision of public or subsidized childcare are crucial. Leaving aside the lockdown, the low level of support characterizing the liberal model of the British welfare state is unlikely to have equalizing effects. In fact, care needs are usually considered as a private issue, and families rely on the market providing services – thus tightening up socioeconomic inequalities, either based on gender or social class.

However, the key issue lies in the gender division of housework, rather than childcare. In this case, the solution is less obvious. We showed that gender inequality struck back after a loss of working hours of the main earner. This suggests a strong relationship between an unequal division of paid work and an unequal reallocation of unpaid work. Shifting therefore the focus to the gender division of paid labour, we could ask: why isn’t female employment and income enough to evade the surplus of domestic tasks?

From a cross-national standpoint, we said that the UK shows high levels of female participation in the labour market, but this is meaningless if we do not dig into the type of jobs held by women. If working women are perceived as the ‘second earners’ in the couple (with temporary, low-paid, part-time contracts), and if the rare female breadwinner households are the result of an unstable employment situation of their male partners, then gender inequalities within the household are unavoidable. To tackle this issue, it is crucial to invest in employment policies, which provide quality jobs for all categories of workers, including women. Achieving greater gender equality in paid labour and wages can thus be a leverage for women to better negotiate the division of domestic tasks and eventually dismantle stale stereotypes.

______________________

Note: the above draws on the authors’ published work in Research in Social Stratification and Mobility.

Anna Zamberlan is a PhD Candidate in Sociology and Social Research at the School of Social Sciences, University of Trento.

Anna Zamberlan is a PhD Candidate in Sociology and Social Research at the School of Social Sciences, University of Trento.

Filippo Gioachin is a PhD Candidate in Sociology and Social Research at the School of Social Sciences, University of Trento.

Filippo Gioachin is a PhD Candidate in Sociology and Social Research at the School of Social Sciences, University of Trento.

Davide Gritti is a PhD Candidate in Sociology and Social Research at the School of Social Sciences, University of Trento.

Davide Gritti is a PhD Candidate in Sociology and Social Research at the School of Social Sciences, University of Trento.

Photo by engin akyurt on Unsplash.

Interesting and the basic idea is certainly plausible, but as a non-academic I struggled to understand how you could compare actual data with predicted results. Surely you need to compare actual with actual to draw safe conclusions? The policy conclusions looked a little vague. We can all agree on the need to improve the quality of work, but the policy agenda to do so appears under-powered because there are few obvious policy levers to pull.

Dear Ian, thank you for your comment. It made us realize that the technical jargon sometimes used in the article might be confusing. “Predicted” results stand indeed for projected values deriving from the estimation of a statistical model, which is of course based on actual data. In other words, we do not present forecast findings, but an analysis of past (although relatively recent) events.

As for the policy implications, our analyses did not enable us to speculate about any specific policy interventions, so we deliberately abstained from discussing them in detail. The aim of the article is, instead, that of highlighting the presence of inequalities and their underlying mechanisms – and this is a necessary step for tackling them.