Why do some voters accept their defeat and agree to a democratic verdict while some do not? Richard Nadeau, Éric Bélanger, and Ece Özlem Atikcan focus on losers’ consent in the Brexit referendum.

Why do some voters accept their defeat and agree to a democratic verdict while some do not? Richard Nadeau, Éric Bélanger, and Ece Özlem Atikcan focus on losers’ consent in the Brexit referendum.

In the protracted aftermath of the 2016 Brexit vote, more than 4.1 million UK citizens signed a petition in early 2019 calling for a second referendum on EU membership. This time they wanted it to be based on new rules in terms of the scale of majority (60%) and the turnout (75%) required to act on the result. Their hopes faded away when the government responded that the decision made in the 2016 referendum ‘must be respected’.

Existing studies in political science suggest that post-electoral reactions by voters are mainly outcome-driven. These accounts consider winners and losers as homogeneous groups; and they neglect the individual-level profile and motivations of ‘graceful losers’. Using an innovative and direct question to measure consent by voters on the losing side, our research finds that their reaction to the outcome is also process-driven.

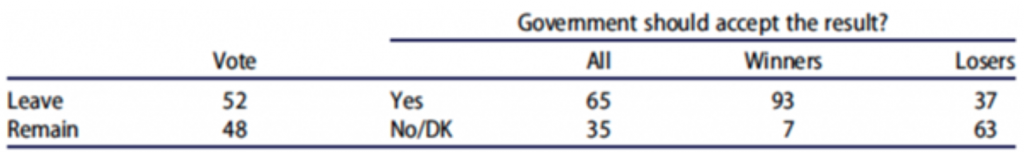

We have three key findings. First, using opinion survey data collected right after the referendum, our research shows the importance of distinguishing between ‘graceful’ and ‘sore’ losers for a better understanding of the crucial phenomenon of losers’ consent. Using a direct question to measure this, Table 1 demonstrates that there are three key groups after an election (not two). Voters on the winning side are overwhelmingly satisfied with the result, but then there are the losers who refuse to recognize the legitimacy of the outcome; and ‘graceful losers’, who accept that appropriate procedural rules have been complied with.

Table 1: Winning and democratic majorities in the 2016 referendum on British membership of the European Union.

Notes: The ‘vote’ column represents the official results (rounded) of the 2016 referendum. The legitimacy question reads as follow: “Do you think that the government should accept the result of the referendum and that the UK should leave the European Union or do you think that the government should not accept the result of the referendum and that a second referendum should be held on this question?”. Source: Survey of 1514 respondents. Fieldwork: 1-5 July 2016. See full article for more information.

Second, our research confirms that these patterns hold when we rely on a less direct but more commonly used variable to measure voters’ acceptance of the result: respondents’ level of satisfaction with democracy. Grouping respondents into two homogeneous blocks, winners and losers, leads to the usual conclusion that satisfaction with democracy is higher among winners (52%) than among losers (45%). However, the level of satisfaction with democracy among ‘graceful losers’ (57%) is not smaller, but in fact slightly higher than that amongst voters on the winning side. By contrast, only 37% of ‘sore’ losers are satisfied with democracy. This 20-point gap for the same variable (57% vs. 37%) between the two groups of losing-side voters is striking. ‘Graceful’ or accepting losing voters are a group that adds to the democratic majority, and provides greater legitimacy to a given political outcome.

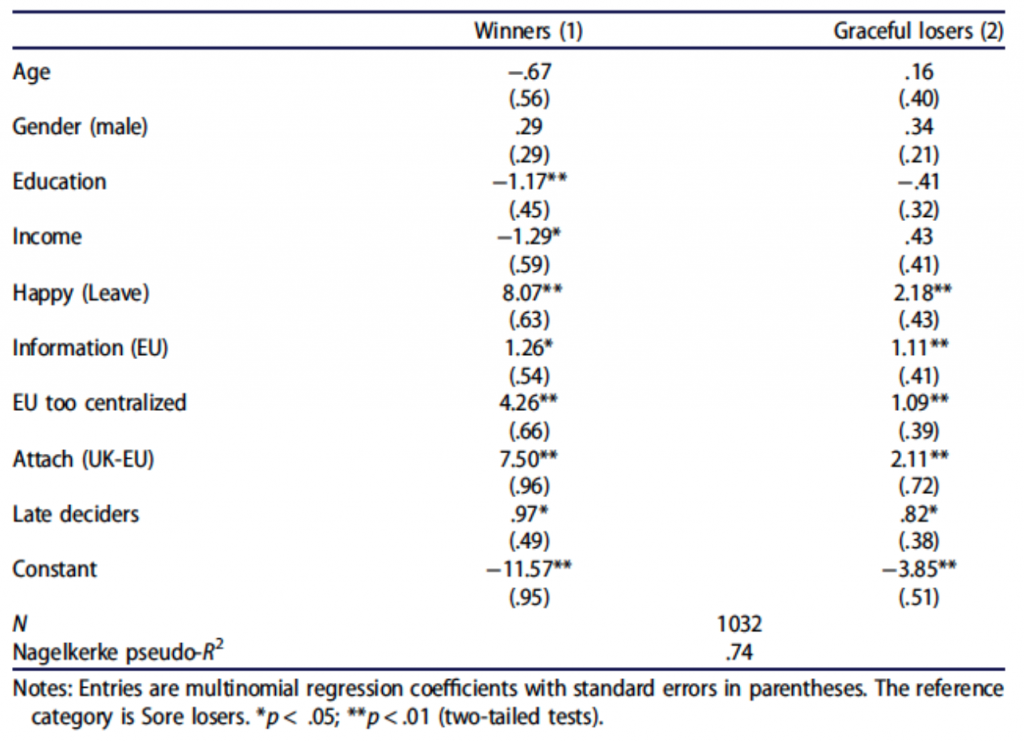

Third, our research examines and compares the distinct attitudinal profiles of these two groups of losers. Table 2 demonstrates that the consent of graceful losers depends on a balance between their emotions, holding moderate opinions, and political sophistication.

Table 2: Multinomial regression model of winners, ‘sore’ losers and ‘graceful’ losers

The results in column 1 are based on the contrast between winners and ‘sore’ losers whereas those in column 2 compare ‘graceful’ and ‘sore’ losers. They indicate that socioeconomic variables are not very useful in discriminating between our three groups of voters. The results in column 2 offer interesting indications of the reasons why ‘graceful’ losers were more willing than the rest of Remainers to accept the referendum outcome. The positive sign of the ‘Happy (to leave)’ variable suggests that ‘graceful’ losers’ reacted to their defeat in a less emotionally intense way than did ‘sore’ losers. Furthermore, the significant result for the Information (about the EU) variable suggests that ‘graceful’ losers’ higher level of sophistication makes them more likely to use democratic principles to form their view of the referendum outcome’s legitimacy – which made them more likely to accept their side’s defeat.

The last three variables in table 2 show that ‘graceful’ losers were driven by contradictory feelings when faced with the options on the table. In a more moderate way than winners, the ‘graceful’ losers saw the EU as too centralized, were more attached to the UK than to the EU and made up their minds relatively late in the Brexit campaign. These variables may be interpreted as reflecting the state of mind of “cross-pressured voters”, who are either ambivalent about the different options or simply have a moderate opinion about the issue of EU membership. The positive coefficient for the variables measuring attachment and EU centralization variables signal that ‘graceful’ losers were less in favour of the EU and more prone to think that it decides too many issues than were ‘sore’ losers. Holding mixed and moderate views about Britain’s EU membership may also explain why ‘graceful’ losers made up their minds how to vote later than ‘sore’ losers did.

Overall, these findings suggest that ‘graceful’ losers over Brexit were politically involved and principled citizens who were more inclined to judge the merits of democracy in procedural terms. In our study they were also more politically sophisticated, less emotionally engaged in the electoral decision, held more moderate views on the object of the vote, and were undecided between the options until the end of the campaign.

These findings have some important implications for democratic theory. Our picture of the equilibrium between emotion and reason buttresses the conventional image of the ideal citizen: informed, sophisticated, committed, and able to overcome their frustrations after a defeat. However, the findings suggest that the stability of democracies may also depend on other groups of voters rarely celebrated by analysts – namely some of the late deciders and those voters torn between contradicting considerations. These two groups have a reputation for being less politically educated and deciding how to vote in emotional or expressive ways. We suggest that the ‘graceful’ losers amongst them are an indispensable component of the democratic majority in the aftermath of an electoral campaign, and that they contribute to the stability of democratic regimes.

________________

Note: the above draws on the authors’ published work the Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties.

Richard Nadeau is Professor

Richard Nadeau is Professor

Éric Bélanger is Professor at McGill University.

Éric Bélanger is Professor at McGill University.

Ece Özlem Atikcan is Associate Professor at University of Warwick.

Ece Özlem Atikcan is Associate Professor at University of Warwick.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Pixabay (Public Domain).

Interesting article, but I believe you’ve based it on an incorrect definition of ‘loser’s consent’.

In a healthy democracy, such consent only requires democratic minorities to accept defeat at the ballot box peacefully, and to trust their turn will come to challenge again in due course.

It bears NO obligation whatsoever for those minorities to conform to the majority view, gracefully, or otherwise.

No matter how heavy a defeat, it’s the right & responsibility of the losing minority to scrutinise, question, and challenge the majority at every turn, and if they can, to make the minority view, the view of a new majority.

Attacking the right to dissent, is the action of an authoritarian state.

Responding with silence, is the inaction of a compliant population.

Compliance isn’t giving ‘loser’s consent’, it’s surrendering the right to disagree, which is characteristic of a dictatorhip.

You cannot be serious. When people are about electoral laws being broken that does not mean they are sore losers. When people care about lies being told that doesn’t make them sore losers. When people care about personal data being stolen so that people can be manipulated, that doesn’t make them sore losers. Have you even heard of Cambridge Analytica? Or did you deliberately ignore it? And what about Northern Ireland and all those people that care about peace and human rights? Are the people who care about the Good Friday Agreement sore losers? What about the people who care about the affect on the economy of the republic of Ireland? I’m embarrassed for you.

I fail to see why ‘graceful losers’ are more politically sophisticated than ‘sore losers’. Maybe they have a lower level of conviction and a lower level of investment in a particular outcome. How does not caring as much about an outcome make them more politically sophisticated? It might be a character trait – accommodation, acceptance, resignation – but is hardly a measure of sophistication.

I’m not sure the Brexit referendum is a good example to use for an analysis of the willingness of losers to accept the outcome of a democratic process. If the decision could be reversed at a subsequent vote then losers (like me) would be more willing to accept the result. Brexit is similar to a decision of a communist or religious party to say that if they win a democratic election it will be the last one a country will have.

I fear Brexit will go badly and all those Sunderland and Scunthorpe Brexit voters will look to people like me to dig them out of a hole while people like James Dyson pontificate from Singapore. But actually I don’t know what the consequences will be – and I don’t think Brexit voters know either.