Geoffroy Duparc-Portier and Gioele Figus use a multi-sector economic model to capture the impact that potential non-tariff barriers and tariffs will have on trade in NI. Simulation results demonstrate that a weaker relation between Britain and the EU will have a greater negative impact on Northern Ireland’s economy. However, this may be reduced by the ability of Northern Irish firms to substitute intermediate inputs from Britain for EU imports.

In 2018, before the UK had withdrawn from the EU, almost 30% of Northern Ireland’s goods purchases came from Great Britain and over 13% from the EU. Goods could circulate free of checks and paperwork as all the regions were part of the EU single market. Since the UK has withdrawn from the EU, such purchases are now subject to new regulations. These regulations are the New Protocol on Northern Ireland and the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA).

The Protocol allows Northern Ireland to stay in the EU’s customs union for goods. This avoids a hard border with the Republic of Ireland and safeguards the Good Friday Agreement. However, since Great Britain is no longer part of the EU’s customs union, the new protocol has led to the introduction of customs checks for goods entering Northern Ireland from Great Britain. These checks were introduced to ensure that these goods align with EU customs rules. The other regulation, the TCA, is an agreement between the UK and the EU allowing for goods to be traded without tariffs or quotas if the products traded meet specific rules of origin. Combined with the UK Internal Market act, which allows Northern Ireland to have unfettered access to the UK single market, these rules now dictate trade in Northern Ireland.

Due to the introduction of these regulations, Northern Ireland finds itself in an unprecedented position: it follows UK rules for services and many of the EU’s customs rules for goods (e.g. animal, dairy products and medicines). Thus, the region now faces non-tariff barriers for goods purchases entering from Great Britain and for service imports and exports to the EU.

We investigate the potential long-term economic impacts of the Protocol on Northern Ireland by using a multi-sectoral economic simulation model. We consider Northern Ireland in isolation, that is eventual spill-overs from other regions, especially Great Britain, are not accounted for. With this research we aimed to find the answers to three main questions.

What is the long-term macroeconomic impact of the NP?

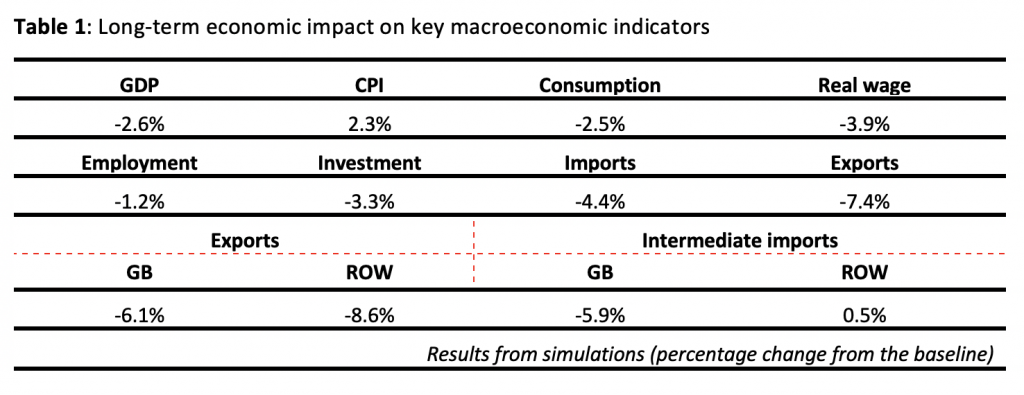

To find the macroeconomic impact of the NP, we analyse the impact that estimated trade frictions can have on Northern Ireland using trade data and information about tariff and non-tariff barriers at a sector-level. We then used this data in a multi-region macroeconomic model built on detailed sector-level data in Northern Ireland. The model with the new trade frictions due to the Protocol is compared against a no-Brexit counterfactual scenario. This allows us to estimate the long run impact of the Protocol on Northern Ireland. The key results are reported in Table 1 below:

Using the model, we find that the non-tariff barriers introduced with the Protocol increase the cost of goods imports from Great Britain relative to a no-Brexit baseline. We also find that the cost of imported and exported services from and to the EU increase. This is reflected in higher production costs for Northern Irish firms, that are in turn forced to increase prices. In the long run, these combined effects could increase the price level in Northern Ireland by 2.3%.

Because of the higher prices and non-tariff barriers for service exports, Northern Ireland becomes less competitive in international markets. This reduces exports to Britain by 6.1% and exports to the rest of the world by 8.6%. Lower exports reduce firm revenues in Northern Ireland. Furthermore, higher prices reduce household consumption. Consequently, Northern Ireland’s total production decreases. With higher prices and lower production, the real wage decreases by 3.9% due to lower competition and demand for labour. Investment is expected to fall by 3.3%.

The combined effects of the new protocol lead to a 2.6% reduction in GDP and a 2.5% reduction in household consumption in Northern Ireland relative to the no-Brexit baseline. This scenario assumes that no tariffs are paid on imports, however a scenario that considers the additional impact of potential tariffs is presented in the paper.

Which sectors are likely to be most impacted by the new protocol?

To answer our second question, we evaluate the sector-level impacts using our macroeconomic model. Using our model, we were able to deduce a few stylised facts. First, we found that most sectors would be negatively impacted by the Protocol. Second, we found that sectors with a high proportion of good output (e.g. agriculture) were impacted more than industries with a focus on service output (e.g. real estate). Third, we found that industries which relied on goods imports from Britain tended to be impacted more negatively (e.g. other primary). The only industry we found to be positively affected by the Protocol was the food and accommodation industry. Since the food and accommodation industry is not highly dependent on imports from Britain and is a service heavy industry, the positive impact was a result of lower wages paid in Northern Ireland due to the Protocol.

What can Northern Ireland do to mitigate the negative impacts of the new protocol?

Based on our results, a few policy recommendations could be made. First, policy solutions should be focused on sectors which primarily sell goods, and which rely on intermediate goods from Britain. Second, policies should aim to reduce the non-tariff barriers between Northern Ireland and Great Britain. This could be through improved border technologies and infrastructure. Third, Northern Ireland should take advantage of its unique position by increasing its imports of goods from the EU to replace good imports from Britain. As Northern Ireland still follows the EU customs rules, it has free and frictionless access to the EU goods market. In fact, we find that the negative effects on GDP would be halved if Northern Ireland was able to switch its supply chain toward EU goods significantly.

_____________________

Note: the above draws on the authors’ published work in Regional Studies.

Authors

Geoffroy Duparc-Portier is a Researcher at the University of Strathclyde.

Gioele Figus is Lecturer at the University of Strathclyde.