Public sector pensions have become ‘bogey of the moment’ for coalition government ministers, following warnings of steep increases in future obligations. Leandro Carrera explains the key issues lying behind the current alarms.

Public sector pensions have become ‘bogey of the moment’ for coalition government ministers, following warnings of steep increases in future obligations. Leandro Carrera explains the key issues lying behind the current alarms.

Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg recently described public sector pensions as “unfair” and increasingly “unaffordable” and declared that significant reform must be adopted in order to contain future spending on them. While private sector workers have seen final-salary schemes closed and the returns of private personal pensions fall, he argued that taxpayers continue to fund “unreformed” and “gold plated” pensions for public servants.

Clegg’s words followed the Office of Budget Responsibility’s pre-budget report, which dedicated a special section to the cost of public sector pensions. OBR forecasts that net spending on public sector pensions, (measured as the total amount of benefit paid less contributions received in those schemes), is expected to increase by an average of 20 percent in real terms from 2009-10 to 2014-15.

But what do we mean when we talk about public sector pensions? Why are the right wing media and some politicians now presenting them as increasingly unaffordable? And what steps can be taken to ensure their future sustainability? A first factor concerns size. Two further aspects are the types of benefit paid and the schemes’ typical funding structure.

The size of public sector pensions schemes

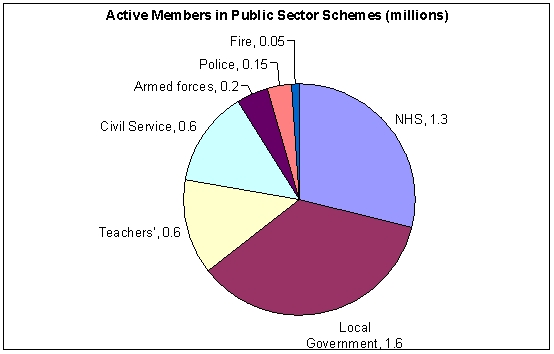

In terms of size, public sector provision in the UK is organized around a small number of key occupational schemes run by and paid for by the government for the benefit of public sector employees. There are seven major schemes which have a combined membership of around 4.5 million active workers contributing to them. In addition, there are a number of smaller schemes for MPs, the Judiciary, and employees from other public corporations – together these total around 0.5 million workers. The chart below shows the membership for the seven major schemes.

Type of benefits

The pension benefit paid by a scheme can be of two types: Defined Contribution (DC) or Defined Benefit (DB). In pension schemes with DC benefits, employee and employer’s contributions are paid into an individual account. This money is then invested in funds that typically include a mix of shares and bonds. The benefit (pension) received upon retirement will be mainly determined by the amount of contributions paid over the employee’s working career and the performance of the investments.

In pension schemes with Defined Benefit (DB) arrangements, the benefit paid upon retirement depends upon a formula that typically considers the number of years of membership in the scheme and a workers’ wage history. Schemes may consider different salary levels: the average of the full worker’s career, the average of the last 10 years, or the salary level in the final year. The latter are usually called final-salary schemes. These are the ones seen as more beneficial for the employee because it is normal to assume that workers’ salary levels tend to be the highest at the moment of retirement.

A final component of the formula to determine the benefit is the accrual rate, typically set at two thirds. This means that a worker with a full contribution career (typically 40 years) can retire on a full pension that will represent two-thirds of earnings after reaching the normal pensionable age. It is important to note that the normal pensionable age in public sector schemes is lower than in the private sector (currently set at 65 but due to increase to 68 by 2046). Civil servants, for instance, retire at 60.

All public sector pension schemes have a defined benefit (DB) arrangement. Until recently, most of the them took into account the final salary for the calculation of the benefit upon retirement with a two-thirds accrual rate.

Funding structure:

This refers to the way in which funds are collected in order to meet the payments for current and future pensioners. A scheme is funded if pensions are paid out of a fund accumulated over the years from employers’ and employees’ contributions, which is usually invested in a number of stock market instruments to ensure proper funding to pay all pensions.

By contrast, a scheme is unfunded, if there is no accumulation of funds and the money from employers and employees’ contributions is directly used to pay for current pensions. This typical unfunded structure is also called Pay-As-You-Go (PAYG). Six of the seven major public pension schemes are PAYG unfunded, with the exception of the Local Government scheme.

It should be noted that in most of these schemes, the funds collected from employers and employees’ contributions are not enough to meet total pension payments and this deficit has to be covered by balancing cash-flows from the Treasury. A recent NAO report has estimated that the combined deficit in 2008-09 for the Armed Forces, Civil Service, NHS and Teachers’ schemes was of £2.4 billion.

Why is the pensions burden growing?

Why is the cost of paying for these pensions increasing so much? And how “unaffordable” can public sector pensions become? The OBR pre-budget report estimated an annual 20 percent increase to fund these pensions to 2014. Long term projections from HM Treasury published in 2009 and reproduced in the NAO report, estimated that the cost of paying for public sector pensions would increase from 1.8 percent of GDP in 2008-09 to 2.2 percent of GDP in 2029. Notwithstanding the caveats in these estimates, which are many and important to consider, it is clear that public sector pension spending is on the rise.

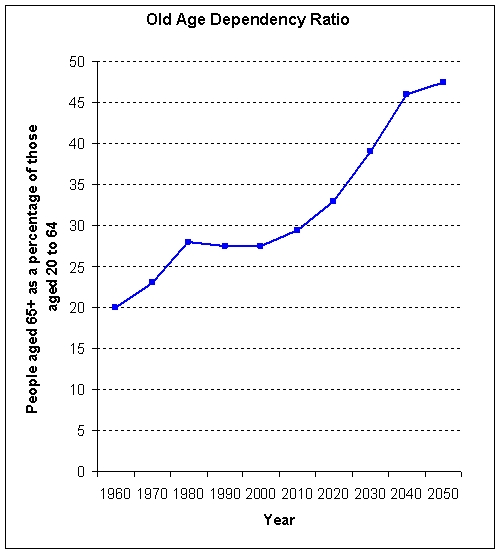

As many experts note, unfunded Defined Benefit (DB) schemes are very sensitive to demographic changes. A key demographic indicator is the old-age dependency ratio, which is the ratio of people aged 65 and over to those between 20 and 64 and that basically tell us how many workers per retiree there are. The chart below shows that the ratio will increase from the current 30 percent to 40 percent by 2030 and will reach almost 50 percent in 2050. So if in 2010 we have 3 workers per retiree in 2050 that ratio will be almost 2 to 1 in 2050. This clearly illustrates the impact of the wave of baby-boomers that are approaching retirement.

Source: Office of National Statistics

Source: Office of National Statistics

Possible reforms

Given this situation, what reforms have and can be implemented to guarantee the affordability of public sector pensions? As Professor Barr noted in an earlier post, the fact that people are living longer is a good thing. But in order to guarantee the affordability of pensions it will be necessary to change some aspects of pension systems such as allowing for later and more flexible retirement.

The previous Labour government already negotiated some far-reaching reforms with public sector unions, mostly reducing the generosity of future pension benefits, and hence applying to new entrants to the schemes but not to current members. The most important changes have been the following:

- Increasing the Normal Pension Age (NPA), which is the minimum age at which members can retire on a full pension. The NPA was increased from 60 to 65 years for new entrants to the NHS, Civil Service and Teachers’ schemes.

- Change in the accrual rate. This means that the benefit paid upon retirement will no longer be two-thirds of salary but lower.

- Change from final salary to career average for new entrants to the Civil Service scheme.

- Increase members’ contribution. This has already been applied to all members of the NHS and Teachers’ fund.

- Late retirement enhancement. This has only been applied to members of the NHS, Teachers’ and Civil Service fund.

Given population aging and the need of future governments to contain public spending, these measures may not be enough. In this scenario, further measures may include more radical changes, such as a change in the defined benefit formula to career average earnings for existing and new members of all schemes.

An even more drastic measure could be to switch from the current unfunded defined benefit arrangement to a funded defined contributions one, as UK private sector companies have been steadily doing throughout the last decade. With political pressure mounting to equalize pension provision among public and private employees, if the government wants to make a major difference it will certainly be looking at these options.

Any future changes will need to be carefully negotiated with the public sector unions. Pensions are highly sensitive issues that people care about deeply, and which govern how they make life choices about where to work. Unison’s General Secretary Dave Prentis has already warned of possible industrial action if reforms are implemented with inadequate negotiations. This is not an issue that will go away any time soon.