Both the Brexit referendum and Trump’s election were fuelled in part by anti-immigration sentiment. Yet both the US and the UK are gradually becoming more tolerant of racial diversity. Maria Sobolewska explores this apparent contradiction between diminishing racial prejudice and a swing to the right on immigration policy.

After the largely unexpected Trump victory in the US presidential elections, the commentators on both sides of the Atlantic have drawn comparisons with the equally unanticipated Brexit vote earlier in the year. The core of many of these stories is the parallel between the revolt of the working class white American voters and the British left behind: similar voters with similar attitudes in two very different countries. Both groups of voters were less educated, older and resident outside of the large global metropolises that increasingly form the focus of economic growth, cultural activity and political influence in both countries. But, while in the UK we focus on these voters’ socio-economic woes and the anti-immigrant rhetoric that won them over in the Brexit campaign, we miss another important parallel: Britain is now – like the US – a racially divided society. White voters identify and mobilise around their whiteness, and hold complex and politically consequential racial attitudes. We need to learn from the US how to measure, analyse and interpret this phenomenon.

The parallels between British racial divisions to the US ones are stronger than one would have thought, given Britain’s different history of slavery, no experience of formalised segregation, or the twentieth century Civil Rights Movement. On the contrary, Britain granted full political rights to the vast majority of her non-white immigrants upon arrival, due to their colonial linkage. As a result we have a positive story to tell about our racial diversity, with non-white representation in Westminster rising sharply, London boasting Europe’s first minority-Muslim mayor, and growing evidence that we are becoming a more racially tolerant society with every generation. Yet, what is often forgotten is that the same is true of the US. Obama hardly needs mentioning as a symbolic victory for racial harmony. The proportion of people opposing inter-racial marriage, a classic measure of prejudice, is falling in the US as well as in the UK; particularly among younger generations. In fact, only a couple of years ago in both countries we all worried about the impossibility of electing right wing governments without them extending their appeal to ethnic and racial minorities. As the members of white majority who hold racially prejudicial views are now a shrinking minority, the rise of such populist options such as UKIP and Trump can successfully mobilised these voters. And it is exactly this common trend, and not the dissimilarity of the past history, that makes the white backlash similar in the UK and the US.

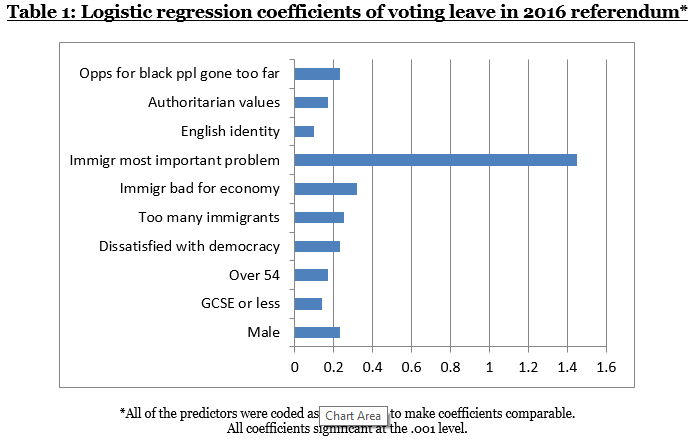

So how can we distinguish the anger these voters feel about immigration from their racial attitudes? In the US we measure these two attitudes separately, while in the UK we don’t. However, the British Election Study contains one race-related item: question whether equal opportunities for black and Asian people in Britain have gone too far. Running the usual explanatory model of Brexit vote (shown in Table 1), including all of the demographics proven to predict a leave vote – as well as many relevant attitudes such as authoritarian values and opinions on immigration- we see that believing that racial equality has gone too far is the second most important predictor of the leave vote after immigration attitudes. Even after controlling for three different immigration-related questions, it holds its own. Given that some overlap between these two attitudes is likely, it is probably an under-estimation of its importance.

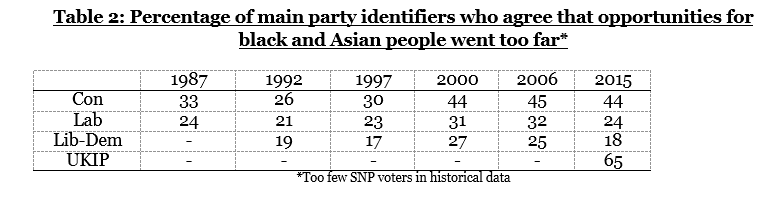

This question has been asked intermittently since the 1980s and Table 2 shows how the percentage of Conservative voters who agree with this statement has gone up significantly, particularly following the New Labour’s victory in 1997. Curiously, supporters of all parties briefly become more critical of equal opportunities for non-whites, before coming back to their pre-1997 levels, perhaps in response to the apparent retreat from multiculturalism post 2010 and losing some of the most racially conservative voters to UKIP. This suggests that the rise of official multiculturalism may have been the trigger here. This further reinforces that it is an attitude towards what is perceived as a racialised policy, rather than straightforward expression of racism, reminiscent of the American opposition to affirmative action politics, which has been one of the strong driving forces in US politics for many decades. Although few British commentators would recognise the New Labour’s agenda as racialised, this seems to be the message that some voters received.

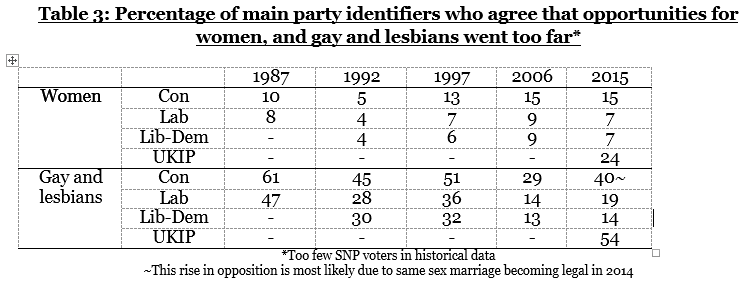

This shift should not, however, be seen as a backlash against diversity in general, despite Stephen Kinnock’s recent suggestion. Race is different than other diversity cleavages and it must be approached on its own. The ‘equality has gone too far’ question has also been asked about women and gays and lesbians (see Table 3). What we see is that while UKIP identifiers are by far the most intolerant of any part of the diversity agenda, the issue of women’s equality is largely uncontroversial even with them. The high levels of opposition to gay and lesbian equality are falling, although we see a continued partisan divide on this issue. In fact, this element of the diversity agenda started as the least popular among British partisans, but resistance has been falling so rapidly that the hostility to racial equality- that has started from a much lower level- has now overtaken those who do not support gay rights.

Thus, while the Labour party is tearing themselves apart over their approach to immigration and how to meet the left behind voters half way, they ignore a serious and potentially growing problem: that Britain is also divided on its attitudes to race and racialised policies. While immigration is an issue on which policy compromises could be achieved, despite certain ideological entrenchment, the issue of diversity is a much more complex one and goes deeper into the heart of liberal left wing values. The compromise on these values aimed at winning back the left behind may cost them the support of the cosmopolitan, educated voters on which they also depend to ever stand a chance of electoral victory. They must think deeply about diversity not as a monolithic issue, and address the distinctions between xenophobia, racism, and racially conservative attitudes more deeply. As shown by the US Democratic party that has been grappling with these issues more openly since the 1960s, without finding a lasting way to resolve them, this may be more difficult than anything the Labour party have thus far envisaged.

—

Maria Sobolewska is a Senior Lecturer in Politics (Quantitative Methods) at the University of Manchester and a member of CoDE – www.ethnicity.ac.uk.

Maria Sobolewska is a Senior Lecturer in Politics (Quantitative Methods) at the University of Manchester and a member of CoDE – www.ethnicity.ac.uk.

Concern about mass immigration is widely held accross society-something which many researchers seem unable to grasp.

I think I undersrand what “White voters identify and mobilise around their whiteness, and hold complex and politically consequential racial attitudes” means, but would ask, what is the evidence?

John Harris posted two very insightful videos about his investigations in Stoke and a journey from South Wales through the Consrrvative shires to Leicester. He found that what unites Brexiters of all social backgrounds is a sense of patriotism-or “our” local community and country.

George Orwell said that there were certain Leftists who would rather admit to robbing the church poor box than to being patriotic. His insight then I believe speaks volumes now.

Agree Kinnock and the Labour right wing are opportunist and wrong to blame working class “racist”Labour voters for leave. They are only interested in one thing. MP’s jobs in Brexit seats.

FOM is not the issue at all. The conflation of EU citizens, asylum seekers (refugees) and migrants has been used to inflame racists. This makes up about 16% of total leave vote. It was the Tories that voted out not working class Labour.

MIGRANT CRISIS main driver across Europe

If diversity is seen more as a result of self-determining constituencies/communities as opposed to diversity based on individualism then the dichotomy between metropolitan cities and left-behind communities is overcome. The state/government then becomes an enabler and a protector of a nationwide network of self-determining communities.