In 2002, an amendment to parliamentary regulations removed restrictions on the participation of MPs in proceedings related to their corporate interests. Colin Green and Swarnodeep Homroy demonstrate how both firms and politicians changed their behaviour as a result. Post-amendment, firms were more likely to appoint MPs on their boards and reduce political donations. MPs with corporate connections were more likely to become members and attend meetings of select and joint committees.

In 2002, an amendment to parliamentary regulations removed restrictions on the participation of MPs in proceedings related to their corporate interests. Colin Green and Swarnodeep Homroy demonstrate how both firms and politicians changed their behaviour as a result. Post-amendment, firms were more likely to appoint MPs on their boards and reduce political donations. MPs with corporate connections were more likely to become members and attend meetings of select and joint committees.

In October 2019, The Guardian reported that oil companies and climate contrarian businessmen had given at least £5m to MPs over the past decade in the form of donations, expenses-paid trips, and salaries. This may seem a small detail in the ongoing churn of the Brexit and COVID-19 news cycles, but it is one that shouldn’t go unnoticed. The interaction of the corporate sector and political representation is a highly controversial and important issue. At its core lies the concern that these interactions lead to the ‘co-option’ of politicians by large corporations, and that politicians will prioritise their own corporate interests over the interests of their electorate.

In our research, we examine the effects of corporate connections of MPs. On 14 May 2002, a legislative amendment came into place in the UK which allowed MPs with outside business interests to initiate parliamentary proceedings on issues that are related to their registered business interests. This occurred in a setting where almost half of the top 50 public companies in the UK had connections with a sitting MP. Beyond showing a return to these political connections to companies, we demonstrate marked changes in both firm and politician behaviour as the value of political connections increases. We do this in the context of a developed, low corruption economy. Although stylised results show that the benefits of political connection are more pronounced in countries with weak legal systems, recent papers show that even in developed economies such as the UK political connections can have substantial effects.

The UK provides an attractive setting to examine the value of political-corporate connections. On the one hand, it has strong legal protection and low corruption: it was ranked the twelfth least corrupt country in the world in 2019 on the Corruption Perception Index. At the same time, within this low-corruption setting, 46% of the top 50 public corporations have connections with a serving MP, and connected companies form 39% of market capitalisation. In comparison, the figures for the US are 6% and 4%, respectively. Globally, only Russia and Thailand have a higher fraction of market capitalisation of politically connected companies.

To measure the effects of this amendment in parliamentary regulations we used data-mining techniques to study the financial performance, stock valuation, board composition and director backgrounds of FTSE 350 companies, as well as details about parliamentary committee attendance and activities of MPs. We cross-referenced this with the list of members of the House of Commons and House of Lords, their declared business interests, and the composition of key committees linked to government contracts and regulatory affairs, such as on defence, trade, and economic affairs. Since the skills and expertise of MPs are unlikely to be influenced by the regulation, at least in the short run, this empirical strategy should solely capture the returns to the change in political access of companies.

Companies with existing connections to MPs experienced higher stock returns in the three-day window [-1,+1] surrounding 14 May 2002 when parliament passed the amendment. Figure 1 illustrates the substantial returns for firms connected to MPs compared to unconnected firms on that date.

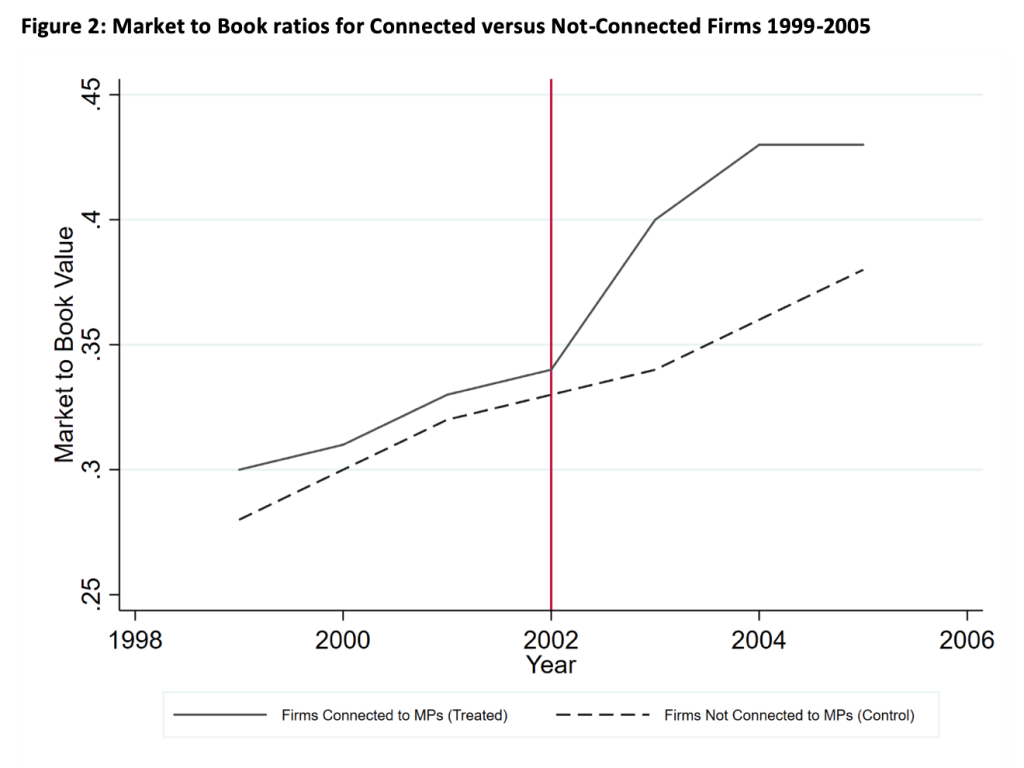

In the longer term, we find that companies with MPs as directors or consultants experienced a substantial gain in value compared to unconnected companies following the introduction of this legislation. These returns were more significant for firms where influence may be more important, for instance, those with concentrated (family) ownership, low attention to corporate and social responsibility, poorer environmental performance, and less transparent accounting practices. Figure 2 illustrates the gain in value for UK companies connected to MPs compared to companies that had no such connections when the amendment was passed. In contrast, companies with links to politicians not affected by this amendment (including Members of European Parliament, ex-MPs, etc.) did not gain in value after the amendment.

In the longer term, we find that companies with MPs as directors or consultants experienced a substantial gain in value compared to unconnected companies following the introduction of this legislation. These returns were more significant for firms where influence may be more important, for instance, those with concentrated (family) ownership, low attention to corporate and social responsibility, poorer environmental performance, and less transparent accounting practices. Figure 2 illustrates the gain in value for UK companies connected to MPs compared to companies that had no such connections when the amendment was passed. In contrast, companies with links to politicians not affected by this amendment (including Members of European Parliament, ex-MPs, etc.) did not gain in value after the amendment.

Beyond these increased financial returns, we demonstrate substantial changes in the behaviour of both corporations and politicians resulting from the amendment. For example, following the amendment, politically connected companies reduced donations to political parties. This highlights the value of direct access to policymaking that was facilitated by the 2002 bill, and hence the reduced influence value of political donations.

Beyond these increased financial returns, we demonstrate substantial changes in the behaviour of both corporations and politicians resulting from the amendment. For example, following the amendment, politically connected companies reduced donations to political parties. This highlights the value of direct access to policymaking that was facilitated by the 2002 bill, and hence the reduced influence value of political donations.

Additionally, we detect an increase in MPs with corporate affiliations. In particular, MPs with no connections before the amendment and with higher electoral majorities were more likely to gain a corporate affiliation afterwards. MPs with links to companies were also more likely to obtain appointments to major parliamentary committees and, conditional on this, more likely to attend meetings: MPs with pre-2002 corporate affiliations were up to 23 percentage points more likely to be appointed to select committees after the amendment when compared with MPs without prior corporate affiliations. This paints a clear picture of manoeuvres to act upon this increased access to parliamentary influence.

We find no evidence that the higher demand in the corporate world leads to increased monetary gains for MPs. This could be due to concerns about electoral and media attention, low discretionary components in non-executive directors’ pay, or companies using non-traditional forms of compensation that we simply do not observe. Additionally, one reason for politicians to gain corporate connections may be better post-political career labour market prospects.

To what extent is the corporate clientism of elected politicians socially desirable? As we see from our results, the companies that benefit more from political connections are not the best corporate citizens (for example, those with poor environmental performance and opaque accounting standards). The role of large corporations in influencing democratic processes is increasingly coming under scrutiny. Our results have implications for the design of policy aimed at regulating and/or restricting these political and corporate interactions, particularly in light of the substitution between the different forms of corporate political connections.

____________________

Colin Green is Professor in the Department of Economics at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

Colin Green is Professor in the Department of Economics at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

Swarnodeep Homroy is Assistant Professor in the Department of Economics and Business at the University of Groningen.

Swarnodeep Homroy is Assistant Professor in the Department of Economics and Business at the University of Groningen.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: by Alexander London on Unsplash.

1 Comments