Consecutive governments have failed to properly address educational inequality in the UK. Is there more hope now that the number of comprehensively educated MPs is growing? Rebecca Montacute explains why politics still remains almost exclusive to the most well off, and what policies could help get more state school pupils into politics.

Consecutive governments have failed to properly address educational inequality in the UK. Is there more hope now that the number of comprehensively educated MPs is growing? Rebecca Montacute explains why politics still remains almost exclusive to the most well off, and what policies could help get more state school pupils into politics.

The 2017 House of Commons has been praised as the most diverse yet, with record percentages of female (44%), BME (8%) and LGBT (7%) MPs elected. New Sutton Trust research has also found that the educational backgrounds of MPs are more representative of the population than ever before, with over half (52%) of 2017 MPs educated in state comprehensive schools, and the number of privately educated MPs at a record low (29%).

But there’s still a long way to go. Just as parliament still underrepresents women, the BME community and the LGBT community, the educational backgrounds of MPs are still very different from the rest of the country. Only 7% of people in the UK have been to an independent school, so MPs are four times more likely than their constituents to have enjoyed a private education. People educated in grammar schools are also over-represented in parliament. Grammar school attendance peaked in the 1960s at 25%, before rapidly falling to around 5% in the 1970s to the present day. Despite this, 17% of our current MPs attended a grammar school.

And change is not coming quickly. At the existing rate, if an election occurs every five years it will take roughly another 12 elections (or 60 years) before the percentage of MPs who are privately educated is the same as the population. Despite the provision of scholarships and bursaries opening up some places, private schools are still dominated by the very rich. Students in the top fifth of household incomes make up 50% of private school pupils, whereas those in the bottom 30% of household incomes take up only 8% of places. Grammar schools also substantially under-represent pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds. Previous research by the Sutton Trust has found that a pupil attending a private prep school is ten times more likely to enter a grammar school than a pupil on free school meals.

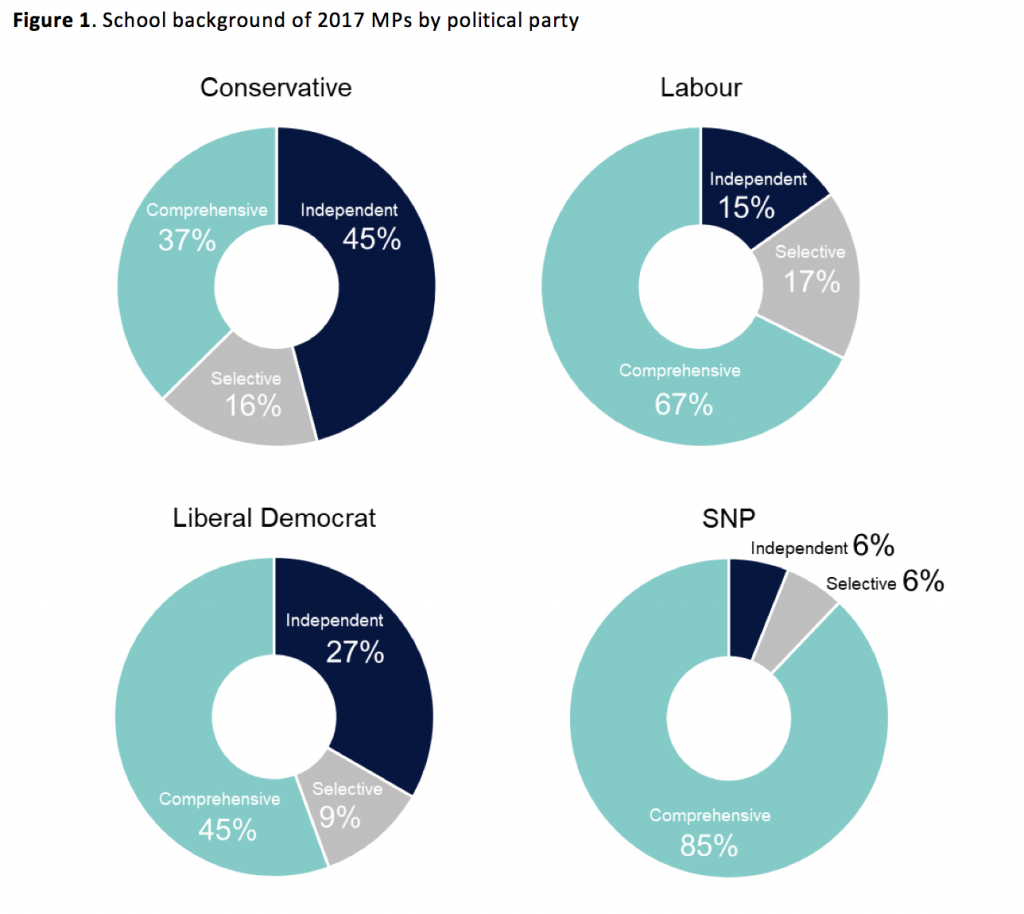

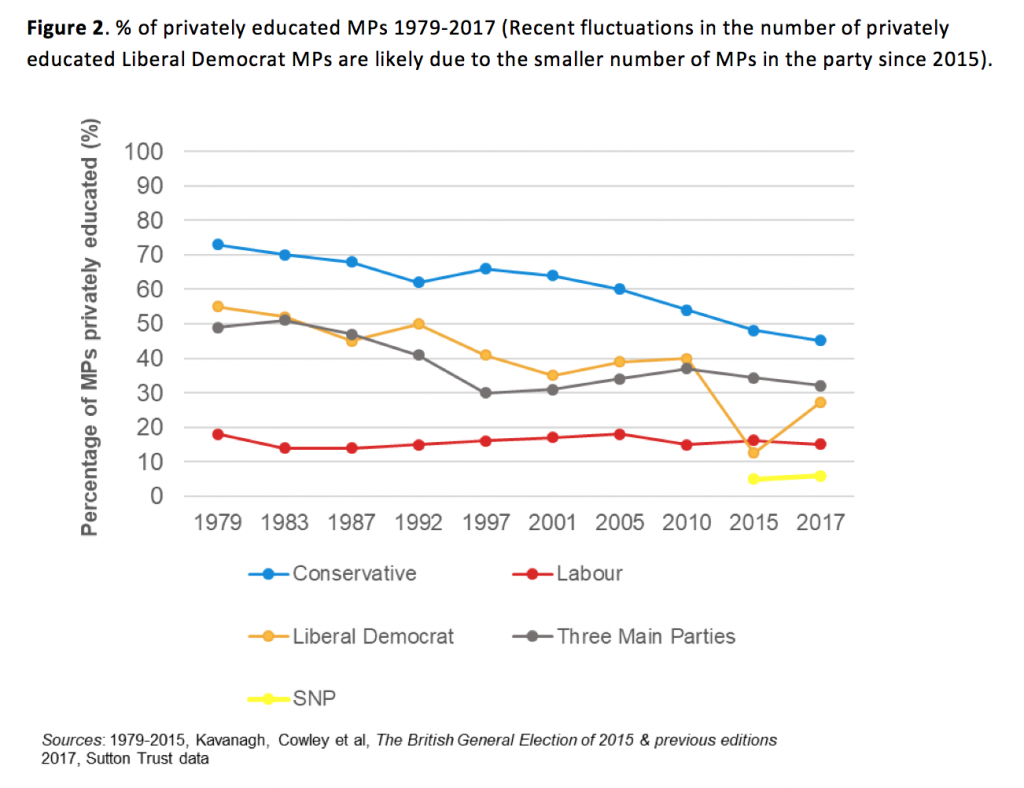

However, some political parties are more representative than others (Figure 1). The Conservative party has the most privately educated MPs at 45%, although this has steadily fallen from over 70% in 1979. The party is also home to all 20 Old Etonian MPs (making up 3% of all MPs). The other major parties have much smaller numbers of privately educated MPs, with 27% of Liberal Democrat MPs and 15% of Labour MPs. The SNP at 6% is the only party with a similar number of privately educated MPs to the population. Trends over time of privately educated MPs in the major parties are shown below in Figure 2.

MPs also attend top universities at much higher rates than the rest of the UK population (see Figure 3). Almost a quarter (24%) of MPs went to Oxbridge, compared to less than 1% of the UK population, and 52% of MPs went to a Russell Group university (including Oxbridge), compared to just 10% of the population. It’s not surprising that MPs are well educated, but it is concerning that highly selective universities so heavily dominate parliament when those institutions are disproportionally attended by the most well off. Students who have attended an independent school are 22 times more likely than pupils on Free School Meals, and six times more likely than all other state school pupils, to enter the most selective universities in the UK.

How can we get more state school pupils into politics? Improving political education in comprehensive schools, and improving access to extracurricular activities which develop skills sought after in politics, such as public speaking and debating, could all help close the gap. Too often comprehensive pupils do not have access to these activities. However, we still know relatively little about why people educated in comprehensives are so much less likely to become MPs. People on low and middle incomes may find it difficult to get experience in politics, with reports of MPs offering unpaid internships and concerns that candidates may be put off by the high cost of living in London. The cost of running as an MP may also be too high for many, with one estimate putting the cost of becoming a candidate, running a campaign, and lost earnings during the process at roughly £34,000 of personal expenses. Political parties must do more to ensure candidates from all backgrounds can gain experience and afford to run for office.

Knowing the backgrounds of our MPs really does matter. The social backgrounds of MPs are still considerably different to those of the population, which means that the worries and concerns of all parts of society are unlikely to be adequately represented by parliament. And importantly, MPs are ultimately responsible for national education policy, and may allow their own experiences to guide the decisions they make. Indeed, the attempted resurrection of grammar schools was driven by a Prime Minister and close advisor (Nick Timothy) who both attended grammar schools themselves. The schools, Theresa May said, would “make this country a true meritocracy” – despite a wealth of evidence that grammar schools under-represent people from disadvantaged backgrounds. For decades, parliament has failed to properly address educational inequality. The hope is that as the number of comprehensively educated MPs continues to grow, a more representative House of Commons will really start to tackle these issues.

______

Rebecca Montacute is Research Fellow at The Sutton Trust.

Rebecca Montacute is Research Fellow at The Sutton Trust.

Comment on Grammar schools is misleading. To be representative of the population at large then you need to age adjust given the collapse of the proportion educated at them. Crude average of the 25% in the 70s and 5% now is 15% which isn’t far from the proportion of MPs educated at them

The Sutton Trust will have the detailed data so we could have been given the real figure by age cohort.

The underlying thrust of the article as regards universities seems absurd. We ought to want as many MPs as possible to have had a top education. It is accepted that Oxbridge and some of the Russell Group are world class. We should be pleased that they are over-represented.

Out of curiosity, how representative of the population is the Sutton Trust: looking at the website it looks to me pretty stuffed full of those educated at elite universities – does that invalidate its work?