While there are procedural reasons that render the appointment of a large number of peers at once unlikely, Mike Kellermann writes that the move would also not make a difference if the aim was to block legislation prohibiting a no-deal Brexit. He explains why hundreds of new peers would be required to ensure such a working majority in the Lords.

Given the challenges facing the Johnson Government in pursuing its Brexit agenda, the idea of packing the House of Lords as a backstop has reemerged. Some recent media coverage indicates that Johnson plans to create around half a dozen new pro-Brexit peers. Other reports suggest that the government would, if necessary, create enough new peers to ensure that the Lords could block any legislation prohibiting a no-deal Brexit. Just how many new peers would be needed?

Voting in the House of Lords

Political scientists often model voting in legislatures as occurring along a single dimension of policy conflict. In the case of Brexit, that dimension would stretch from peers who want to remain in the EU on one side, to those who would leave the EU immediately with no deal on the other. In principle, we could line up all of the current peers from one extreme to the other along this dimension. In that case, the Median Voter Theorem says that whichever peer is exactly in the middle (i.e., the median) along this policy dimension would have the most influence over the legislative outcome. The logic is simple. If a proposal to move policy in the direction of a hard Brexit had the support of the median peer, it would also have the support of every other peer who was more pro-Brexit than the median peer, thus giving that proposal the support of a majority in the House of Lords.

The trick is figuring out where each peer is located on the spectrum of positions on Brexit. I estimate those positions, known in the literature as ideal points, by applying a statistical model to peers’ votes on Brexit-related divisions over the past two and a half years. If a peer voted in favour of a second referendum, for example, the statistical model places them toward the anti-Brexit end of the spectrum. On the other hand, voting to delay consideration of the Cooper-Letwin bill requiring an extension of the Article 50 transition period indicates that a peer was somewhere on the pro-Brexit end of the spectrum. As the results of a statistical model, the ideal points are estimated with some uncertainty.

Which peers are pivotal today?

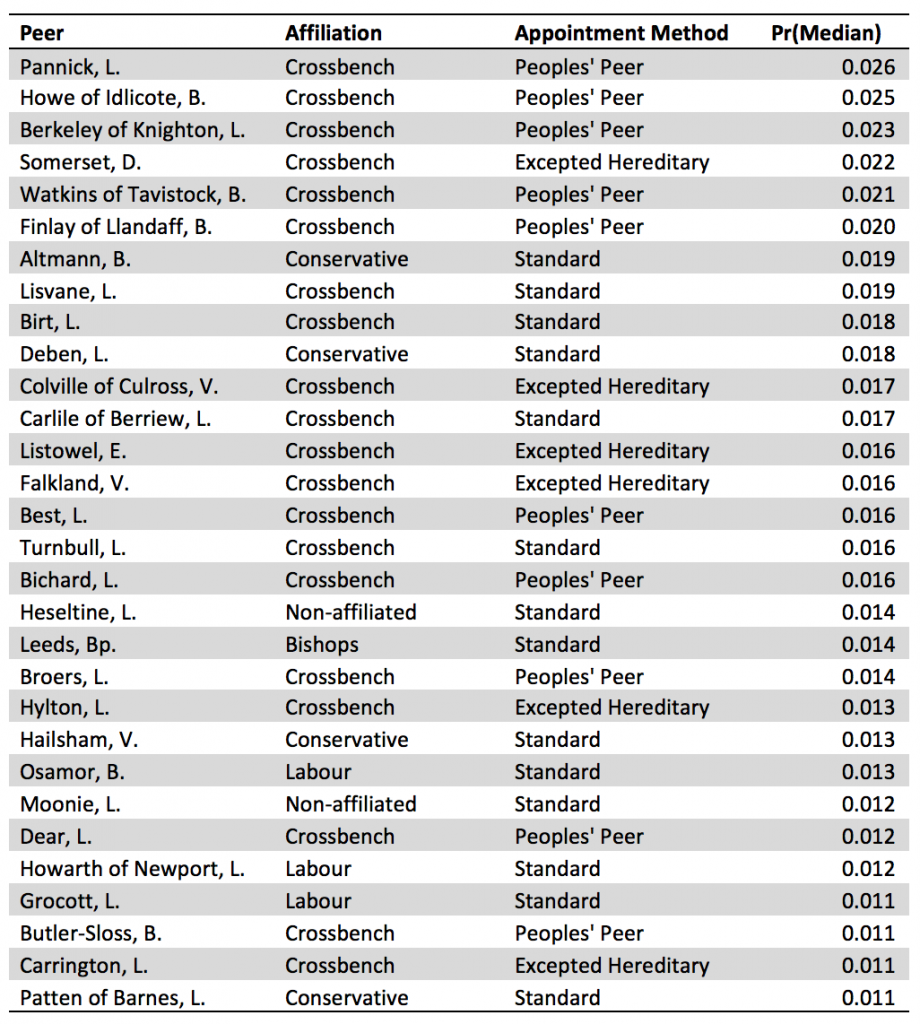

Given the uncertainty in the ideal point estimates, it is impossible to say definitively which peer is the median voter today. What we can do is identify a group of peers who are relatively likely to be the median. These peers are the most likely to be pivotal on Brexit given the current composition of the House of Lords. The 30 peers with the highest likelihood of being the median voter are listed in the table below:

Table: Probability of being Median Peer as of 1 September 2019 (Top 30 Peers)

The peer who is most likely to be the median voter on Brexit is Lord Pannick, but he has only a 2.5% chance of being exactly the median. Collectively, though, there is about a 50% chance that one of these 30 peers is the median Brexit voter. Unlike their Liberal Democrat colleagues, these peers have not sought to move policy in a strongly pro-Remain direction. At the same time, it seems unlikely that these peers would vote to block the House of Commons from preventing a no-deal Brexit, hence the government’s reported interest in creating new peers.

How many peers would it take?

The key question is then, how many new peers would be needed to ensure a working majority for Johnson in the House of Lords? Adding six new peers would hardly change anything; it would only move the median by three peers, leaving essentially the same group of peers in a pivotal position.

To make a difference, the government would have to shift the median peer in the expanded House of Lords to a point well within the current Conservative caucus. To illustrate, assume that Johnson and his advisers believe that they can count on the support of half of the current Conservative peers, plus other peers with similar preferences. The peer in the middle of the current Conservative caucus is ranked about 630th on Brexit in the House of Lords as a whole. To make that person the median of the entire house, Johnson would need a house of 1260 peers, requiring approximately 480 new peers. If they were more optimistic and believed they would get the support of 75% of existing Conservative peers and other peers with similar views, they would still need a house of 1110 peers, or about 330 new peers.

The challenge of packing the Lords is two-fold: (1) the current House of Lords, as some of its Conservative critics suggest, is not a particularly pro-Brexit body, and (2) because the House would be packed by adding new peers, rather than replacing existing peers, the location of the median peer moves slowly. It requires two new peers to move the median by one peer. Tinkering around the edges would not get the job done; successful packing requires a wholesale revamping of the composition of the Lords, with whatever political ramifications that would have.

Complications

The analysis above assumes that the preferences of existing peers would not change after a successful packing of the House of Lords. This may not be realistic. On one hand, Conservative and crossbench peers who generally supported the May government could be turned off by Johnson’s more aggressive parliamentary tactics. If so, the number of new peers needed to ensure a pro-Johnson majority would increase.

On the other hand, existing peers may react to the threat of Lords-packing by changing their voting behavior to make it unnecessary. If new peers are appointed, those who are currently pivotal will lose influence in future votes. In theory, acquiescence by current peers in exchange for not creating new peers could be a rational response if the threat to pack the House of Lords was seen as credible.

Finally, any attempt to pack the House of Lords would run into a variety of challenges, beyond the political controversy that would ensue. There would undoubtedly be legal challenges to the creation of so many new peers; likewise, nominees must be vetted by the House of Lords Appointments Commission, which could prove logistically difficult if hundreds of new peers are created. This last requirement, however, does not have a statutory basis, and a government willing to accept the political price of packing the Lords could find a way around it.

________________

Note: the above draws on research presented by the author at the American Political Science Association annual conference. The views expressed here are the author’s and not those of the U.S. Naval Academy or the US Government.

Mike Kellermann is Associate Professor in Political Science, United States Naval Academy.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Greggy1900 is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0