The beleaguered Big Society concept argues that not-for-profit organizations can and should deliver a much larger proportion of the ‘caring’ services in education, social care and the health sectors. Sarah Smith finds that these providers do have clear advantages over for-profit organizations in these sectors. But they also often have high costs, and their ability to do more looks unclear.

The beleaguered Big Society concept argues that not-for-profit organizations can and should deliver a much larger proportion of the ‘caring’ services in education, social care and the health sectors. Sarah Smith finds that these providers do have clear advantages over for-profit organizations in these sectors. But they also often have high costs, and their ability to do more looks unclear.

A greater role for not-for-profits – both in contracting to deliver public services, such as the Work Programme, and also in stepping in to provide services affected by recent public spending cuts – has formed a key part of the government’s Big Society argument. There is an underlying assumption that not-for-profits have a lot to offer, but the arguments and evidence have not been clearly presented by Cameron or other ministers.

These two images capture many of the strengths and potential weaknesses of not-for-profits. On the left, sitting beside David Cameron, is Camilla Batmangheligdh – described as Britain’s most colourful charity leader. She is well-known as the founder of Kids Company, a charity that works with vulnerable and traumatised children in London. On the right, together with Madonna, is Michael Berg. The Berg family are involved in the Kaballah organisation and a number of charities, including Raising Malawi and Spirituality for Kids.

Two faces of not-for-profits

The absence of a profit motive credibly commits not-for-profits to a “mission”. Compared to the public sector, not-for-profits offer diversity without the concern associated with the private sector that the profit motive may undermine the quality of service provision. However, whether not-for-profits are desirable depends a lot on the mission’s value. The organisation’s mission may be perceived as valuable, as in the case of Kids Company, but it may also be narrowly ideological, as in the case of Spirituality for Kids.

Another potential advantage of mission-driven organisations, again illustrated by both the Kids Company and Spirituality for Kids is that they can attract similarly-motivated people. In turn this commitment can translate into extra effort in service provision (or at least effort without the need for high-powered incentives). However, in this respect, the evidence suggests that not-for-profits do not have a particular advantage compared to the public sector. My first Table below stems from work that we have done at Bristol. It takes unpaid overtime as an indicator of extra effort, and shows that workers in the non-profit sector (both not-for-profit and public) are more likely to put in extra effort than similar workers in similar organisations in the for-profit sector. However, there are no significant differences between workers in not-for-profit organisations and workers in the public sector in this key respect.

Table 1: The proportion (%) of workers doing any unpaid overtime in the UK

| Percentage (%) of worker reporting doing any unpaid overtime | ||||

| Not-for-profit sector | Public sector | Private (non-profit) sector | Private (for-profit) sector | |

| Education | 59 | 47 | ||

| Social care | 43 | 15 | ||

| Health | 31 | 23 | ||

| All ‘caring’ services | 49 | 46 | 46 | 29 |

Source: British Household Panel Survey

One potential disadvantage of not-for-profits is that they may have higher costs compared to for-profit organisations. This could be for a number of reasons. First, there may be some cost in producing the extra mission. This is fine if the mission is valued, although tools such as social return on investment may be needed to capture the value. Second, not-for-profit status may be relatively more attractive for higher cost firms, essentially because the cost in terms of giving up profit is lower. And finally, competitive pressure on costs may be muted both by the absence of owners and by the tax advantages that many not-for-profits enjoy.

Offsetting this is the fact that many not-for-profits can attract donations of money and volunteer time, allowing them to deliver services more cheaply. This is likely to be seen as a major advantage by a cash-strapped government. What is less clear is the potential for levels of charitable giving and volunteering to increase substantially. The evidence suggests that levels of giving compare favourably by international standards, and by historical standards.

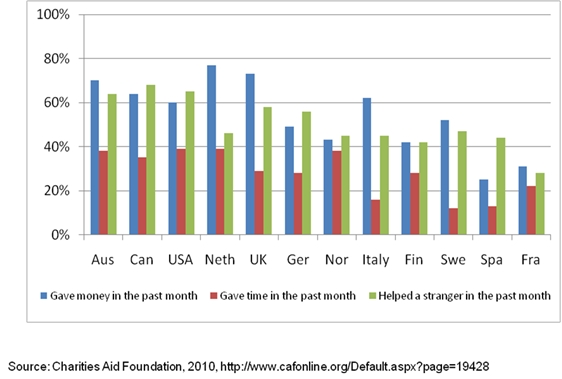

Earlier this year, the man appointed by David Cameron to be his “Big Society Tsar”, Lord Wei, announced he was cutting back on his unpaid role from three to two days a week in order to earn more money and to spend time with his family. In his own words, his volunteering contribution was incompatible with “having a life”. It is certainly possible that the government can increase donations of both time and money. But the evidence suggests that many people are already making a big contribution and may not have the time (or money) to do a lot more. My first Chart below shows that the proportion of people giving money to charities the UK is already in the top two of the countries covered, and the UK scores well already on helping a stranger in the past month and on giving time to charities.

Chart 1: How many people give money or time to charities across countries

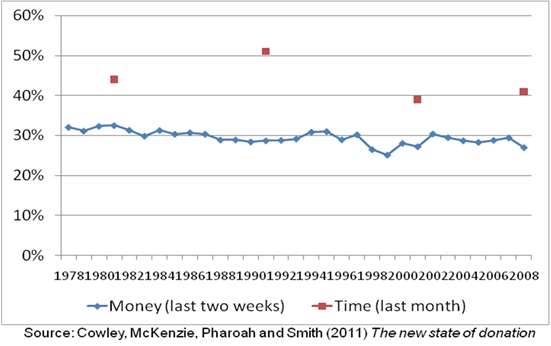

Looking at the historical trends over three decades from 1978 to 2008, my second Chart shows that the proportion of people in the UK who have given money to charities has gradually declined over time. We only have isolated data points for the percentage of people giving time, but here too the recent trend seems to be static or downward. Reversing such well-established patterns may be difficult to do.

Chart 2: The proportion of people giving money or time to charities in the UK since 1978

Sarah Smith is one of four LSE academics speaking at the Social Market Foundation’s new lunchtime seminar series, Chalk + Talk, with a talk on 11 August, Can the Big Society deliver public services? The Chalk + Talk series consist of free lunchtime talks bringing some of the best policy output from the world of academia right into the heart of Westminster. Further details are below or on the Chalk + Talk webpage at www.smf.co.uk/chalk-and-talk. If you’d like to attend, simply register online via Eventbrite

Please read our comments policy before posting.