Thomas Elston and Yuxi Zhang quantify, for the first time, the implementation of Public Accounts Committee recommendations in Whitehall. They find two-thirds of actions are reported as complete within 12 months of their target date, but also note signs of gaming by government departments keen on exaggerating their responsiveness to the committee.

Thomas Elston and Yuxi Zhang quantify, for the first time, the implementation of Public Accounts Committee recommendations in Whitehall. They find two-thirds of actions are reported as complete within 12 months of their target date, but also note signs of gaming by government departments keen on exaggerating their responsiveness to the committee.

The Committee of Public Accounts, also known as the Public Accounts Committee (PAC), is the oldest and, reputedly, most influential committee of back-bench MPs currently in the British House of Commons. Dating from Gladstone’s time as chancellor, and supported by the formidable National Audit Office whose origins are similarly Victorian, the PAC has been described as the ‘queen of the select committees‘ and ‘first among equals‘.

The PAC is particularly known for ‘keeping many senior mandarins on their toes‘ through the system of departmental accounting officers, by which permanent secretaries, rather than ministers, are held personally responsible for public expenditure. But the PAC is also recognised as a valuable ‘ally’ of HM Treasury, given their shared interest in securing value for money across government.

Ostensibly, Whitehall departments formally ‘accept’ nearly 90% of recommendations made by the PAC, compared with just 40% for other departmental committees. And yet, as Benton and Russell argue, ‘We … cannot be confident about the ultimate success of [committee] recommendations without additional information on their actual implementation’.

So, does government deliver the changes desired by and promised to the PAC? In December 2010, the House of Commons passed a motion, tabled by the then committee chair Margaret Hodge, ‘call[ing] on the Government to ensure that all [PAC] recommendations … accepted by Government Departments are implemented, and that the relevant Minister makes a statement to the House on any recommendations accepted but not implemented within a year of their acceptance’. In January 2012, the Treasury Officer of accounts issued the first progress report responding to this request for greater transparency, and the sixteenth such report was issued by late 2021.

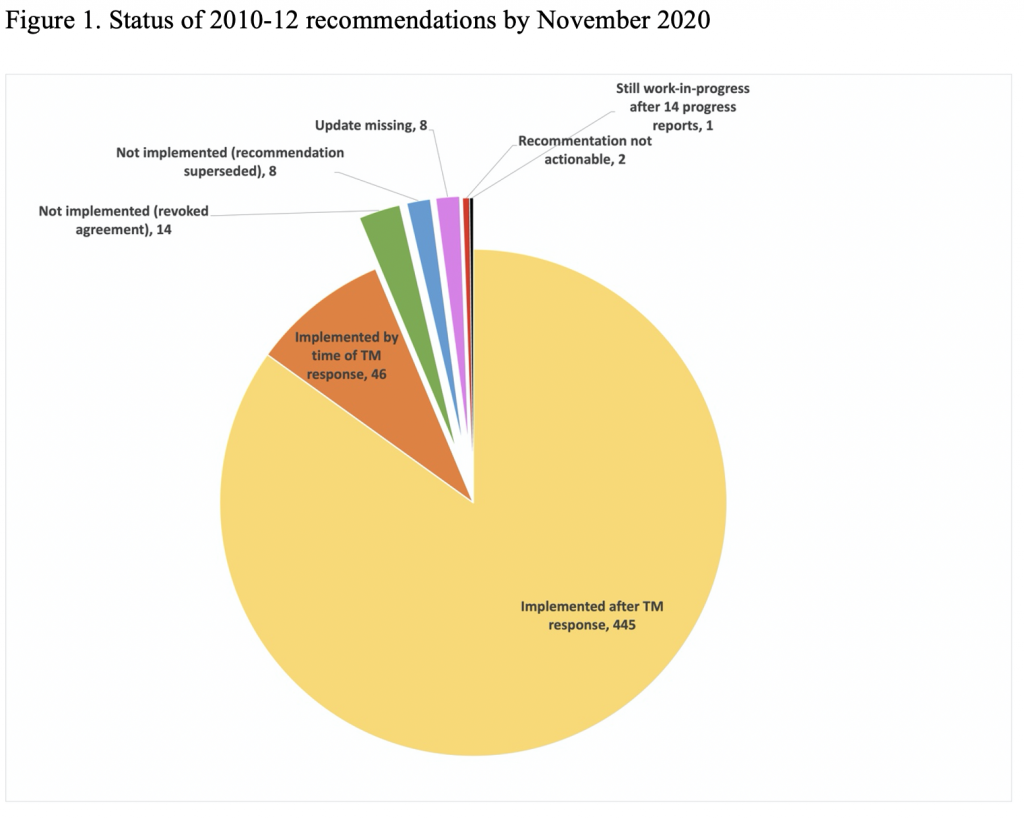

Our project tracked all 524 government-accepted actions from the 2010-12 parliament across the first fourteen of these progress reports up to November 2020. As Figure 1 illustrates, the overwhelming majority (93.7%) are self-reported as implemented by that time. For the remainder, government either revoked its initial acceptance during implementation (2.7%), or the suggested actions were superseded by new reports or policy changes (1.5%), or departments failed to provide an update (1.5%). Only one recommendation (concerning debt collection by the Department for Education) was still ‘work-in-progress’ at the end of the period we studied.

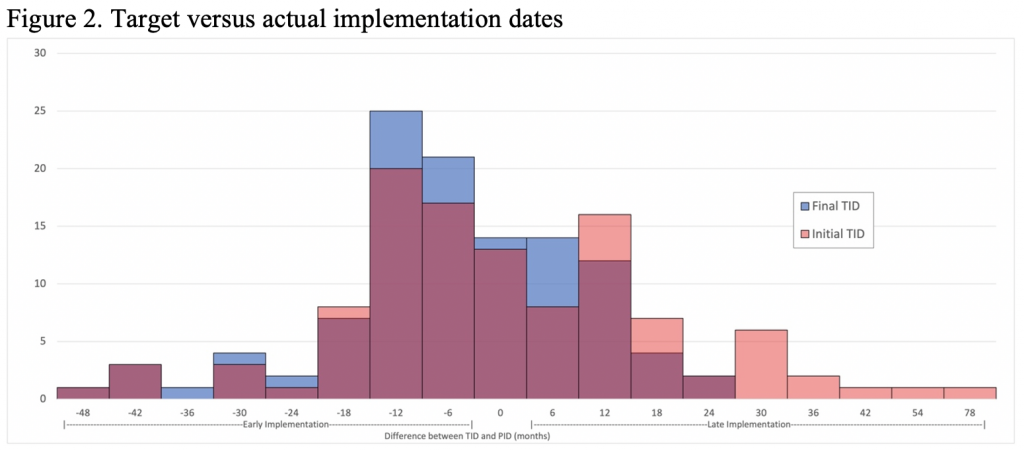

So much for the final status of recommendations. But how quickly did the government complete this work? Figure 2 compares the ‘target implementation dates’ (TIDs) that departments set themselves for each achieving accepted recommendation with the self-reported completion for the 110 cases (out of 524) for which both data points are available. Because departments sometimes revise targets during implementation, the figure contains two overlapping histograms: one comparing performance against the initial TIDs (pink), the other using the final TIDs (blue). As the Figure shows, around one-third were completed within six months (early or late) of the initial timetable set out by government, and two-thirds within 12 months. Revised timetables improved the government’s scorecard considerably, however, with 11 extra recommendations completed within six months of the (modified) target, and no action closing more than 24 months late.

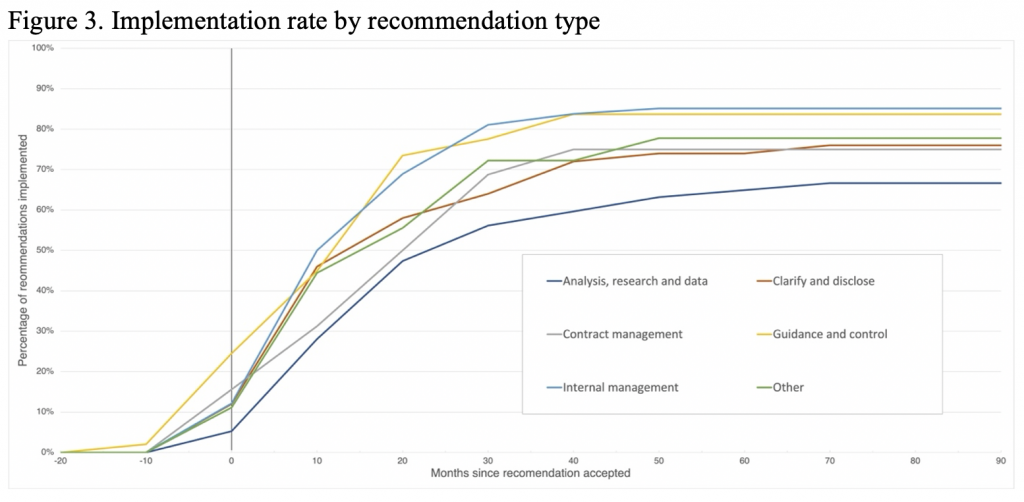

What explains this variance? Figure 3 compares pace of implementation across six types of recommendation made by the committee. Those suggesting changes to internal management practices and the issuing of guidance and control of arm’s-length bodies achieve both the fullest and most rapid implementation. Recommendations regarding contract management of outsourced service providers and the clarification and disclosure of information occupy an intermediate position. Lastly, analysis, research and data achieves the slowest trajectory and lowest completion rate, reflecting the long lead time for research and departments’ tendency to (mis-)report such actions as completed before the results of the research are known.

Irrespective of how quickly government reported these actions as complete, what do we know of the quality of implementation? Although in this initial analysis we lacked the resources to compare what the committee asked for with what the government ultimately delivered, we do find signs of possible ‘gaming’ – that is, misrepresentation or exaggeration of compliance.

For example, in November 2011, the PAC recommended that the Department of Health clarify its rules regarding use of personal budgets by users of social care, and develop a complaints process. The department accepted but revised its intended timeline three times, finally arriving at a target date of April 2016. In certifying the action as complete, however, the promised new appeal system was dropped, with only a promise of future work on appeals by April 2020, more than four years hence. Similarly, early in 2012, government was asked to release the information it relies upon to evaluate local flood authorities’ risk management strategies. Despite being a relatively straightforward ‘disclosure’ request, a vague and distant target date three years hence was provided by Defra, by which time the department promised to have completed such an evaluation. In the event, the action was closed early with no such review having been undertaken, and with the department simply pointing to material already in the public domain as fulfilling its obligations. Such examples illustrate the flexibility with which departments report actions as completed – even for cases of significant under-delivery.

Overall, although no system of performance monitoring is perfect, there are clearly refinements that should be made to strengthen usability and usefulness of the progress reporting process, and reduce the risk of gaming. Fixed reporting windows, a transparent and immovable publication schedule, and a requirement to, whenever meaningful, provide precise completion dates would also help combat many of the problems noted above. Greater insistence on departments setting and justifying timelines, and regulation of revisions to them, would also help. And the Treasury should develop and enforce explicit guidelines on the circumstances in which accounting officers can self-report actions as ‘implemented’ or ‘completed’, and on ways in which departments should indicate what elements of the PAC’s recommendation are not being taken forward or have been dropped.

Going forward, this novel dataset also raises the prospect of undertaking extensive new research into factors affecting the speed and quality of government action in response to legislative oversight, the alleged strength of the PAC compared to other select committees, and whether this is evolving over time.

____________________

Note: The above draws on the authors’ published work in Parliamentary Affairs. The analysis was funded by the Research England Strategic Priorities Fund, and the University of Oxford John Fell Fund.

Thomas Elston is Associate Professor in Public Administration at the Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford.

Thomas Elston is Associate Professor in Public Administration at the Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford.

Yuxi Zhang is a Research Fellow at the LSE-Fudan Global Public Policy Hub of the School of Public Policy, LSE.

Yuxi Zhang is a Research Fellow at the LSE-Fudan Global Public Policy Hub of the School of Public Policy, LSE.