Fraser McMillan finds that Scottish administrations between 1999 and 2011 fulfilled their campaign pledges at a rate comparable to Westminster governments. This finding reinforces the notion that the reality of post-devolution governance fell short of its designers’ ambitions for a more consensual politics.

Fraser McMillan finds that Scottish administrations between 1999 and 2011 fulfilled their campaign pledges at a rate comparable to Westminster governments. This finding reinforces the notion that the reality of post-devolution governance fell short of its designers’ ambitions for a more consensual politics.

The idea that election-winning political parties receive a mandate to enact their policy programmes is a cornerstone of representative democracy. Campaign promises are typically published in compilations known as manifestos, which are a convenient vehicle for parties to hash out internal policy disputes, capture media attention, and provide guidance to activists and candidates. Yet few ordinary citizens read party manifestos, and the belief that politicians don’t keep their promises is widespread. Contrary to this conventional wisdom, however, parties take the policy content of their manifestos very seriously. Existing political science research on programme-to-policy linkage shows that parties can be relied upon to enact a healthy majority of their election pledges once in office. The contrast between this repeated finding and public beliefs about campaign promises even has a name: the pledge paradox.

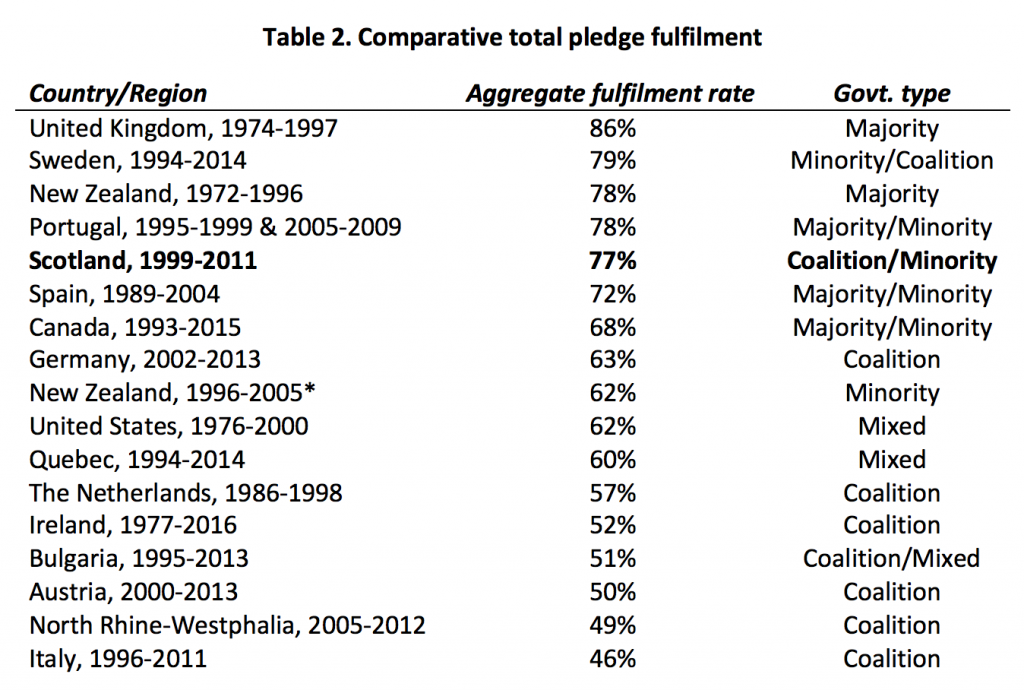

That said, there is significant nuance in what researchers have discovered about the linkage. The key takeaway from the previous literature is that political power facilitates pledge fulfilment. All else being equal, parties ruling alone carry out a greater share of pledges than those serving in coalition with others. Even within coalition governments, the partner in control of the chief executive office tends to enact more promises. Because power-sharing is historically uncommon in the majoritarian and highly centralised Westminster system, the linkage is stronger in the UK than anywhere else: combined, the five British governments serving between 1974 and 1997 fulfilled 86% of their election pledges.

Do institutions and political power tell the whole story? In a recent article, I explored whether or not this is the case with an investigation of pledge fulfilment in Scotland following devolution, the institutions of which were designed using Westminster as a ‘negative template‘. The Scottish Parliament was created with the express intention of inculcating a more consensual new politics. According to the architects of devolution, the Consultative Steering Group, the new legislature was to function ‘as the central institution of a new political and community culture’. The centrepiece of their efforts was the mixed-member proportional (MMP) electoral system, which combines Westminster-style single-member constituencies with multi-member regional-level districts.

It was hoped that by preventing single-party domination and improving the representation of minor parties, MMP would foster a spirit of cross-party cooperation and disabuse Scottish voters of the majoritarian, confrontational assumptions of UK political life. Given what we know about the conditions which shape the programme-to-policy linkage, had this aim been achieved, we would expect to observe a precipitous decline in the proportion of pledges fulfilled at Holyrood compared to Westminster. This did not happen to any significant extent, reinforcing the established view that devolution in practice fell short of the ambitions of its designers.

From a purely numerical perspective MMP worked as intended. Just one of five elections to date has resulted in a single-party majority government: the 2011 Scottish National Party landslide, which the party used to legislate for the ultimately unsuccessful – but politically transformational – referendum on Scottish independence. I investigated pledge fulfilment by the preceding three governments, comprising two Labour-Liberal Democrat majority coalitions (elected 1999 and 2003) and one SNP minority administration (elected 2007). Did the inter-party bargaining and consensus-building necessitated in these sessions dilute the strength of the party mandate in Scotland?

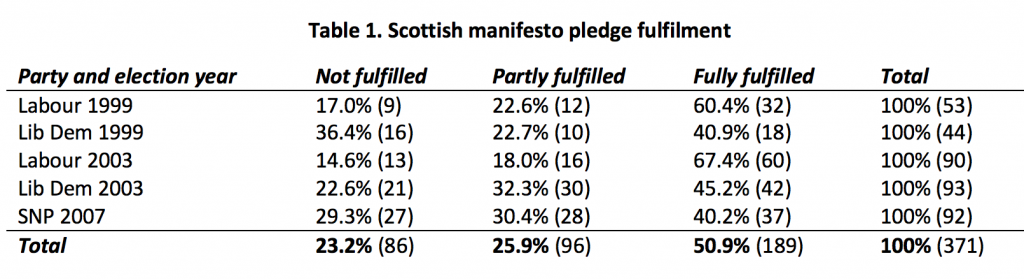

To answer this question, I recorded pledges made on the topics of justice and education – two policy areas which have always been fully devolved – from the five party manifestos. I categorised pledges according to the standard academic definition: ‘a statement committing a party to one specific action or outcome that can be clearly determined to have occurred or not’. I identified 371 separate commitments and then checked them for fulfilment in legislation, Scottish Government publications, executive actions, press releases and the news media.

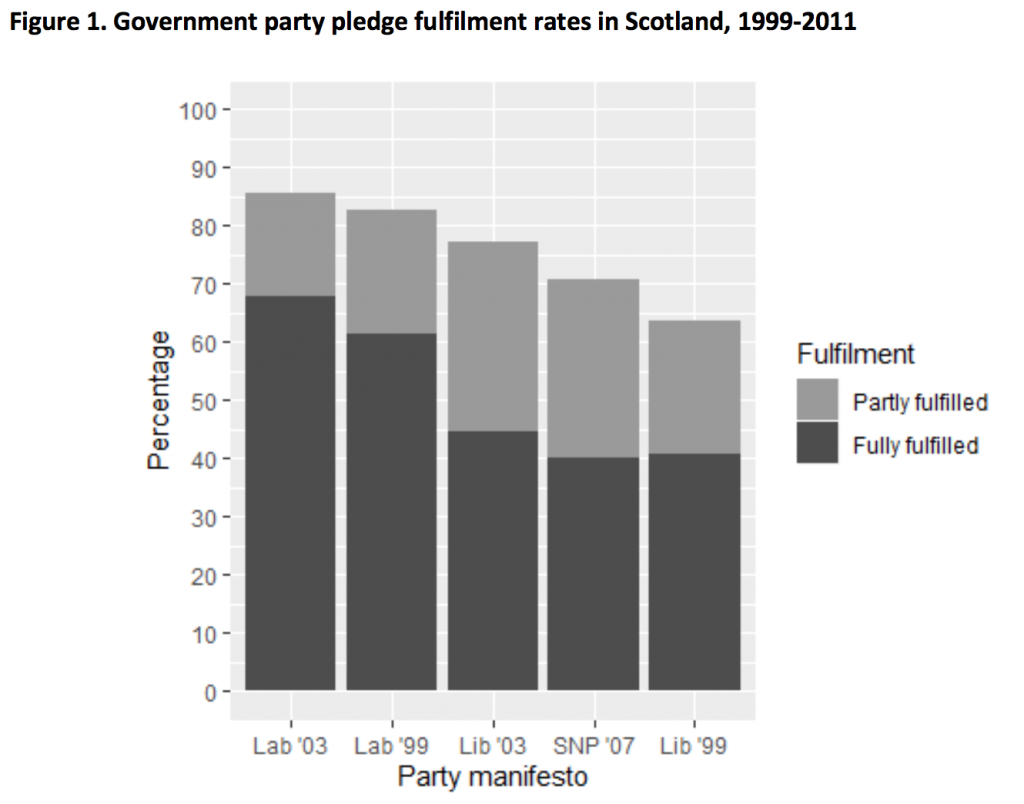

Table 1 shows the percentage of pledges fulfilled from each manifesto. The same data is visualised in Figure 1 below.

A convincing majority pledges from each manifesto were enacted at least partially. The Scottish Labour party seems to have imitated its UK counterpart, fulfilling more than 80% of each manifesto. As the junior partner in government, in line with expectations, the Liberal Democrats’ fulfilment rate was somewhat lower in both sessions. Yet they still enacted most of their own policy priorities, significantly increasing the rate of fulfilment in the second session despite more than doubling the number of pledges made. Perhaps aided by the parties’ ideological similarities, the coalition governed as if it was a single-party majority. Furthermore, the experience in government, and of partnership, resulted in both more campaign pledges and higher fulfilment rates for both parties. This aligns with previous claims that executive dominance increased in this period.

Although minority government status does not typically hamper pledge fulfilment, the SNP found itself in an especially weak position for an election winner in 2007. With just a single-seat advantage over their bitter rivals Labour, and unable to form a coalition government, the party was forced to go it alone with the informal, ad hoc support of the Scottish Conservatives. Far from being paralysed, however, the administration was stable and productive, generating a comparable amount of legislation to its predecessors and otherwise working around parliament using alternative policy tools. The story of executive dominance in the legislature was unchanged, and the party was able to fulfil more than 70% of its pledges.

So, the first three Scottish governments after devolution enacted the lion’s share of their campaign pledges. How does this compare to other systems? Table 2 shows the overall rate of fulfilment in Scotland compared to a selection of other cases. Scotland clearly bucks the trend of consensus systems producing significantly lower pledge fulfilment rates, and of mandates weakening at lower levels of government. Although the aggregate pledge fulfilment rate in Scotland is somewhat lower than UK-level – with a total of 77% compared to 86% over the years studied so far – the difference is significantly smaller, and the overall rate of fulfilment considerably higher, than other multi-level comparisons have shown in Canada/Quebec and Germany/North Rhine-Westphalia, and in New Zealand following the country’s change in electoral system. Scottish executives, as others have observed, seem to behave much like their counterparts at Westminster. The Westminster legacy has evidently been difficult to shake off in Scotland: as the process of devolution enters its third decade, my research provides further evidence that the institutions designed by the CSG were not enough to transform a deeply entrenched political culture and achieve these aims.

Of course, Scottish voters might be pleasantly surprised to learn that Holyrood’s parties take their campaign promises seriously. In this sense, it is not necessarily a bad thing that certain aspects of new politics failed to materialise. This hints a basic truth the designers of devolution overlooked: institutional change inevitably involves tradeoffs.

____________________

Note: the above draws on the authors published work in British Politics. Part of the research for this article was completed at the office of Lewis Macdonald MSP during a voluntary unpaid internship in late 2012.

Fraser McMillan (@frasmcm) is Research Associate at the University of Glasgow.

Fraser McMillan (@frasmcm) is Research Associate at the University of Glasgow.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Pixabay (Public Domain).