The story of the referendum is usually told through geography: areas that had been left behind by globalisation voted to Leave. But this tells us only so much, writes Eric Kaufmann. Knowing where Leave voters live does not, in itself, explain why individuals chose to vote a certain way. Here, he demonstrates the importance of invisible differences between groups, and argues that it was primarily values that motivated voters, not economic inequality.

The story of the referendum is usually told through geography: areas that had been left behind by globalisation voted to Leave. But this tells us only so much, writes Eric Kaufmann. Knowing where Leave voters live does not, in itself, explain why individuals chose to vote a certain way. Here, he demonstrates the importance of invisible differences between groups, and argues that it was primarily values that motivated voters, not economic inequality.

Britain’s choice to vote Leave, we are told, is a protest by those left behind by modernisation and globalisation. London versus the regions, poor versus rich. Nothing could be further from the truth. Brexit voters, like Trump supporters, are motivated by identity, not economics. Age, education, national identity and ethnicity are more important than income or occupation. But to get to the nub of the Leave-Remain divide, we need to go even deeper, to the level of attitudes and personality.

Strikingly, the visible differences between groups are less important than invisible differences between individuals. These don’t pit one group against another, they slice through groups, communities and even families. Our brains deal better with groups than personality differences because we latch onto the visible stuff. It’s easy to imagine a young student or London professional voting Remain; or a working-class man with a northern accent backing Leave.

Open and Closed personalities are harder to conjure up: yet these invisible differences are the ones that count most – around two or three times as much as the group differences. A second problem is that many analyses are spatial. Don’t get me wrong: I love maps and differences between place are important, especially for first-past-the-post elections. However, some characteristics vary a lot over space and others don’t.

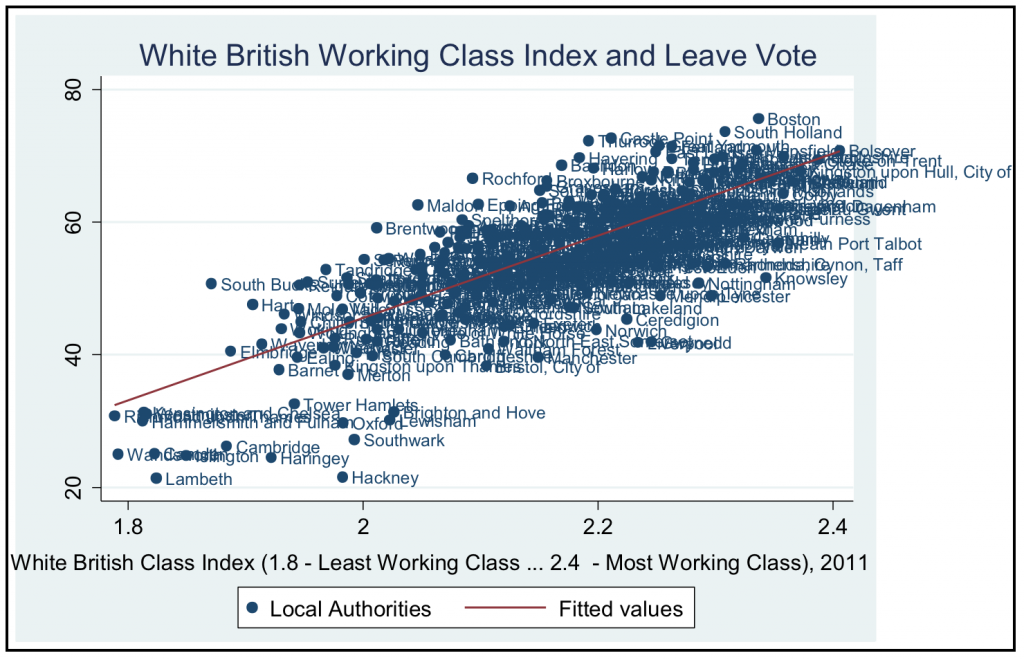

Figure 1 ranks Local Authorities and England and Wales by the average social grade of their White British residents. The lower the average class position of White British residents, the higher the vote for Brexit. In fact, this working class index explains 58 per cent of the variation in the Leave vote across districts. But, according to the 2015 British Election Study Internet Panel of over 24,000 respondents, class only explains 1-2 per cent of the variation in Brexit voting intention among individuals. There may have been a slight shift over the past year, but this won’t have altered the results much.

Figure 1, source: Census data; Electoral Commission

Why the discrepancy? Social characteristics such as class, ethnicity or region are related to where people live, so they vary from place to place. Psychology and personality do vary over space a little because they are affected a bit by social characteristics like age. But they are mainly shaped by birth order, genetics, life experiences and other influences which vary within, not across, districts.

Aggregate analysis distorts individual relationships even when there aren’t problems caused by the ecological fallacy. The sex ratio, for instance, is more or less the same from one place to another, so even if gender really mattered for the vote, maps hide this truth. On the other hand, maps can also exaggerate. If 1 per cent of Cornwall votes for the Cornish nationalists then Cornwall would light up on a map of Cornish nationalist voting with a 100 per cent correlation. But knowing that all Cornish nationalist voters live in Cornwall doesn’t tell us much about why people vote for Cornish nationalists.

As with region in the case of Cornish nationalism, class matters for the vote over space because it affects, or reflects, where we live. This tells us a lot about a little. Notice the range of district average class scores in figure 1 runs only from 1.8 to 2.4 whereas individuals’ class scores range from 1 (AB) to 4 (DE). The average difference from the mean between individuals is ten times as great as that between districts.

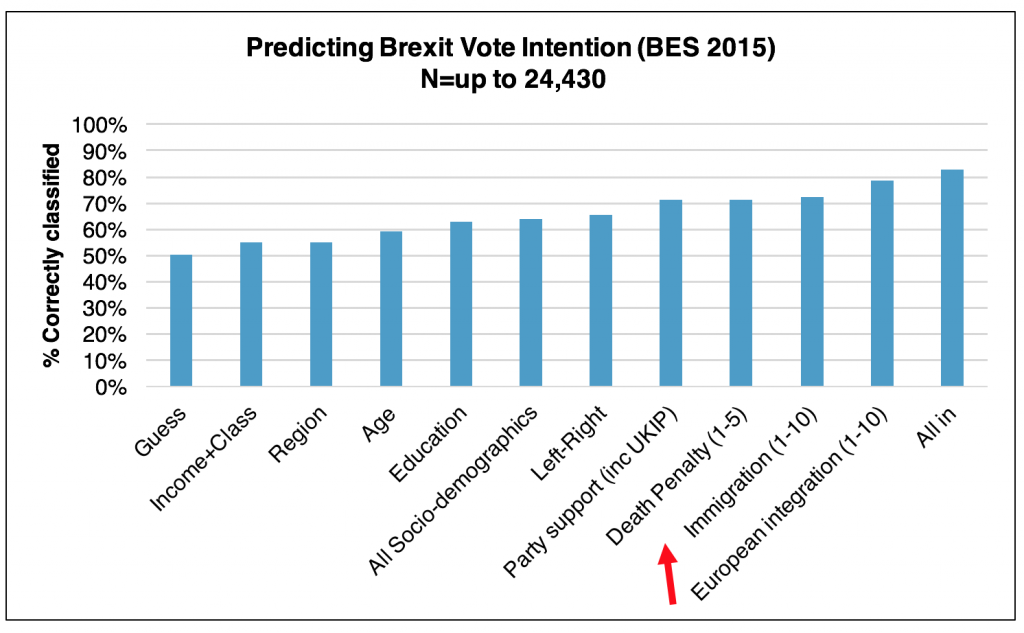

Let’s therefore look at individuals: what the survey data tell us about why people voted Brexit. Imagine you have a thousand British voters and must determine which way they voted. Figure 2 shows that if you guess, knowing nothing about them, you’ll get 50 percent right on average. Armed with information on region or their economic situation – income and social grade – your hit rate improves to about 54 percent, not much better than chance. In other words, the big stories about haves versus have-nots, or London versus the regions, are less important.

Age or education, which are tied more strongly to identity, get you over 60 percent. Ethnicity is important but tricky: minorities are much less likely to have voted Leave, but this tells us nothing about the White British majority so doesn’t improve our overall predictive power much.

Invisible attitudes are more powerful than group categories. If we know whether someone supports UKIP, Labour or some other party, we increase our score to over 70 percent. The same is true for a person’s immigration attitudes. Knowing whether someone thinks European unification has gone too far takes us close to 80 percent accuracy. But then, this is pretty much the same as asking about Brexit, minus a bit of risk appetite.

Figure 2, source: British Election Study 2015 Internet Panel, waves 1-3

For me, what really stands out about figure 2 is the importance of support for the death penalty. Nobody has been out campaigning on this issue, yet it strongly correlates with Brexit voting intention. This speaks to a deeper personality dimension which social psychologists like Bob Altemeyer – unfortunately in my view – dub Right-Wing Authoritarianism (RWA). A less judgmental way of thinking about RWA is order versus openness. The order-openness divide is emerging as the key political cleavage, overshadowing the left-right economic dimension. This was noticed as early as the mid-1970s by Daniel Bell, but has become more pronounced as the aging West’s ethnic transformation has accelerated.

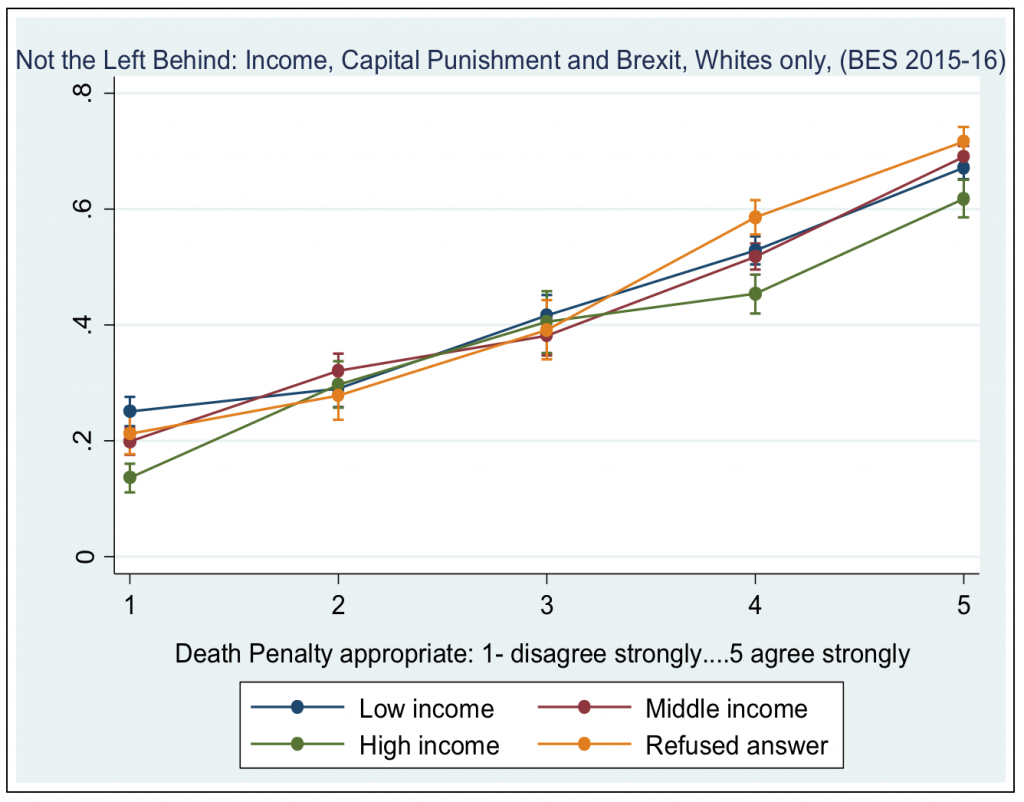

Figure 3 shows that 71 percent of those most in favour of the death penalty indicated in 2015 that they would vote to leave the EU. This falls to 20 percent among those most opposed to capital punishment. A similar picture results for other RWA questions such as the importance of disciplining children. RWA is only tangentially related to demographics. Education, class, income, gender and age play a role, but explain less than 10 percent of the variation in support for the death penalty.

Figure 3, source: British Election Study 2015 Internet Panel, waves 1-3.

Figure 3, source: British Election Study 2015 Internet Panel, waves 1-3.

Karen Stenner, author of the Authoritarian Dynamic, argues that people are divided between those who dislike difference – signifying a disordered identity and environment – and those who embrace it. The former abhor both ethnic and moral diversity. Many see the world as a dangerous place and wish to protect themselves from it.

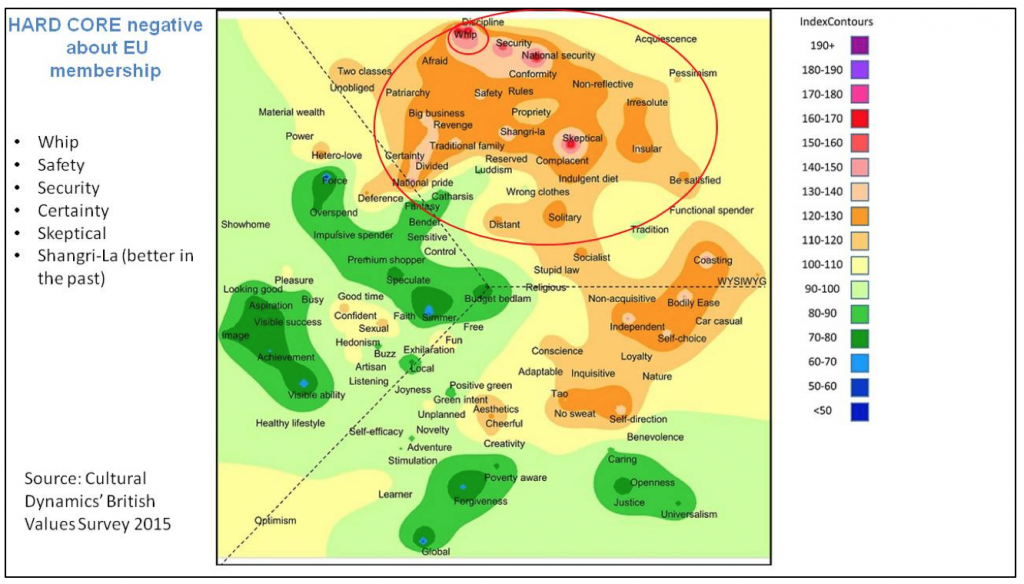

Pat Dade at Cultural Dynamics has produced a heat map of the kinds of values that correspond to strong Euroscepticism, and to each other. This is shown in figure 4. Disciplining children and whipping sex criminals (circled), keeping the nation safe, protecting social order and skepticism (‘few products live up to the claims of their advertisers…products don’t last as long as they used to’) correlate with Brexit sentiment. These attitude dimensions cluster within the third of the map known as the ‘Settlers’, for whom belonging, certainty, roots and safety are paramount. This segment is also disproportionately opposed to immigration in virtually every country Dade has sampled. By contrast, people oriented toward success and display (‘Prospectors’), or who prioritise expressive individualism and cultural equality (‘Pioneers’) voted Remain.

Figure 4.

Figure 4.

All told, the Brexit story is mainly about values, not economic inequality.

____

Eric Kaufmann is Professor of Politics at Birkbeck College, University of London. He is the author of The Rise and Fall of Anglo-America: the decline of dominant ethnicity in the United States (Harvard 2004), Shall the Religious Inherit the Earth (Profile 2011). His latest publication is a Demos report, freely available, entitled Changing Places: the White British response to ethnic change. He may be found on twitter @epkaufm.

Eric Kaufmann is Professor of Politics at Birkbeck College, University of London. He is the author of The Rise and Fall of Anglo-America: the decline of dominant ethnicity in the United States (Harvard 2004), Shall the Religious Inherit the Earth (Profile 2011). His latest publication is a Demos report, freely available, entitled Changing Places: the White British response to ethnic change. He may be found on twitter @epkaufm.

Let’s talk about the ”western interference” factor and the influence in British policies too.

Foreign office is really pro-Europe, because its really anti-Europe like the Yes-Minister series teached us.

https://www.qmul.ac.uk/media/news/2018/hss/charles-de-gaulle–the-unlikely-prophet-of-brexit.html

Marvelous, what a website it is! This blog gives helpful facts to us,

keep it up.

This recent article regarding Trumpism has a deeply woven interpretation that includes values, economic inequality and perceptions of unfairness which mirrors very well John Harris’s work on Brexit (Guardian).

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2016/11/08/a-new-theory-for-why-trump-voters-are-so-angry-that-actually-makes-sense/

All of those views existed pre-economic crash – it’s taken a decade of declining living standards to crystallise them into a political movement. It is the economy, although I wouldn’t dream of calling you stupid.

“All of those views existed pre-economic crash – it’s taken a decade of declining living standards to crystallise them into a political movement. It is the economy, although I wouldn’t dream of calling you stupid.”

But living standards *haven’t* been declining. The UK and the US are the two of the Western countries that have sailed through the financial crash with the smallest impact on growth and unemployment.

The reflex response by a lot of commentators to the lack of evidence for the easy narrative …

… has been to repeatedly move the goalposts. Yes, okay there hasn’t been a jump in unemployment – but what about underemployment? So living standards haven’t fallen – they absolutely must have fallen for some fraction of the population! Or if not fallen, then remained ‘stagnant’ – that’s the real cause!

Obviously, there is no way to respond to that, because it’s essentially dishonest. You’re either in the market for accepting that your intuitions might be wrong – or you’re not.

There’s real evidence of a narrative of “disappointing economics for people who had expectations of continuous improvement” – but it’s awfully hard to frame that as a reason for revolt given that there are Western countries that have been hit far harder who don’t show that pattern.

It’s also not bourne out on an individual level – if economic hardship is the core driver then when we control for social conservatism and plot income against support for Trump/Brexit we should see no/weak association with soc con/lib and a really strong one with income. Instead, we see the opposite.

Marios

Having said all that, there is something really significant in this “All of those views existed pre-economic crash”.

It’s not easy to substantiate this, but insofar as there is evidence it suggests that you’re quite right – people don’t appear to have suddenly become socially conservative/changed their mind on the death penalty/right way to raise kids overnight.

So it’s an entirely reasonable question to say “what’s changed?”.

You’re absolutely right that movements take time to organise – but that’s not a fundamental explanation of why now (just why these movements took time to get going).

I think the parsimonious explanation is that people more or less always felt this way, it’s just that 20th century politics (post WWII, at least) always boiled down to a choice between an economic-left party and an economic-right party.

Partly that’s a reflection of a UK constitution in which plebiscites are not (until recently) common – you don’t get an answer if you don’t ask the question (and people remain unaware that there is actually an electoral majority for a position).

But it’s also a reflection of the dominance of economic-left/economic-right differentiation in post-war 20th century politics. Bear in mind that has always been *heavily managed* dominance.

E.g. It was a Labour prime minister who changed British law so that Commonwealth citizens – specifically in response to ~100,000 of British Asians getting turfed out of Kenya, being made deliberately stateless despite having British passports that they had been given on independence guaranteeing future repatriation – would no longer have the right to immigrate (“”) to the UK (because, as he wrote in his notes, they might have British passports and excluding them might be a violation of the European Convention on Human Rights *that we wrote* – but surely that only applied to people with a racial connection to a country!).

It’s fair to say that both major parties made sure that the main point of differentiation was the economic-left/right split by largely moving in close lockstep when it comes to the social conservative/social liberal divide.

But that still relies on a strong sense among people that the economic left/right split is the *most* salient divide in society.

And it feels like that is dead all over the West. People’s values haven’t changed – but the priority order of the significance of those values has flipped like the flipping of the earth’s magnetic field.

Marios

This analysis regarding the election of Trump agrees with you.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2016/11/08/a-new-theory-for-why-trump-voters-are-so-angry-that-actually-makes-sense/

…..For me, what really stands out about figure 2 is the importance of support for the death penalty…

For me, what really stands out is the lack of data on the NUMBER of people who supported the Death Penalty and voted Leave. I suspect that you will find it’s a VERY small figure.

I don’t buy this “Openness v Authoritarianism” personality argument he tries to make. He says it’s about “values” and not “economic inequality”, but where does he think these values come from if not economic inequality? Economic inequality is what leads people to be afraid and seek simplistic secure solutions in an authoritarian figure. It’s what happens when you have inequality, or economic meltdown (1930s?). It’s nothing to do with “personality values” that we are somehow born with.

Ian,

Actually there is lots of research which shows that personality is genetically inherited and relatively stable over time (whereas economic conditions might not be). You can think of the brain as running from personality through cognitive and emotional neural processes which interact and feedback on one another, but our personality is prior to the other two.

My question for Erik is why use RWA (or related) which is now fairly old-school- albeit hugely influential- and not either Jost’s measure or, even better, the Big 5 personality traits which most political psychologists now use. Do the results hold up? Or even improve? I imagine Openess and Conscientiousness would be doing most of the work, although which individual facets, I don’t know. Also, perhaps worth investigating Haidt’s stuff on purity and immigration and liberals’ “missing moral sense”? I know that some papers were withdrawn because of faulty coding, so I am not sure where that research agenda is at nowadays.

Anyway, interesting stuff and a good piece,

Simon

If values are inherited and stable over time, how come older people are more likely to vote leave?

All well and good, but it doesn’t explain why the Britain of 1975 — an infinitely more conservative, ethnically and politically homogeneous nation, and one in which the last hangings had taken place a mere decade before — voted to remain in “Europe” by a 3-1 margin but then, 41 years later, voted by a small, but substantial majority to leave.

According to Kaufman’s analysis, the result of 1975 should have gone the opposite way.

You fail to acknowledge that the E.E.C. and the E.U. are completely different. What people voted to remain members of in 1975 is not what those people voted to leave in 2016. Interestingly, many, many immigrants, particularly non-E.U. and those known as B.A.M.E., voted to leave than most people give credit, therefore “Brexit” was seen as racist, or xenophobic, whilst for those immigrants, when it came to immigration, it was actually about fairness, not exclusion. The immigration debate, particularly on the left, has had the theme of E.U. immigration good; non-E.U. immigration bad. Even in the reporting of the immigration figures, the fall in the number of E.U. immigrants was lamented and the number of non-E.U. immigrants, by comparison was criticised yet, E.U. immigrants were grossly overrepresented in the immigration figures. This lack of equity drove many of those B.A.M.E. peoples to vote to leave yet this is barely explored in this article, all that is said is that they are “much less likely to have voted Leave.” In an article which sites vales as the prime reason for people voting to leave, I am surprised that there isn’t an examination of why, given the suggestion, B.A.M.E. peoples voted to leave at all. Are they not open? Are they afraid of change? I fear that the author has simplified something that he, himself, has said is complex.

Great Article!

In fact, I’m so impressed* that I decided to sit down, get a copy of the data (starting with the BES data) and try to replicate those results.

I have the BES dataset (waves 1-3) open in a jupyter notebook (sitting in a public github repo if anyone is interested: https://github.com/MariosRichards/BES_analysis_code – note: only an hour or two into a rough draft).

This isn’t an interesting “my goodness, I get the opposite result to you” post – so far everything I see is entirely consistent with your results – just a pedantic “specifically, how did you build those graphs? I want to make sure I actually *am* replicating the same results exactly”

Marios

I find it interesting how we have junior doctors demonstrating, southern rail workers striking and I believe teachers will be striking soon, and no one thinks could it be something wrong at the top of government? If people in several respectful professions are protesting democratically through civil disobedience against austerity, doesn’t this suggest that this is one of many reasons why it doesn’t actually work? In addition, xenophobia is an excellent way for the rich , powerful multinational companies to not be accountable through the control of the media by scaremongering, for example, avoiding accountability for the economic crash by pushing the blame elsewhere. In contrast, I can’t think of one t.v. documentary on the hardships refugees are faced with being televised for the British public. Where is the evidence of an awakened social conscience of the British people? The questions, answers and concerns of the British people are all constructed by the media in terms of money rather than morality.

Another interesting point is I wonder if the same people who want the human rights act amended so we can sent immigrants back to their own country to get tortured and murdered, could these be the same group of people who want the death penalty reintroduced?

Interesting to show how values may influence the leave vote through statistical evidence in terms of values of Openness vs Order. However, I believe it goes deeper than stating it is not about the economy, it is about values. By saying this it gives people in more priviledged economic conditions and higher social status an opportunity to avoid accountabiilty. Therefore maintaining and promoting an unjust and unequal status quo.

I remember Tony Benn saying that people swing to the right when they feel under threat. In my view, this would suggest that fear mongering in the media would promote the activation of more right wing values in people if they think uncritically and are consequently influenced by it. In support of this view, researchers in cognitive therapy has shown that when certain emotions are triggered this leads to certain rigid and dichotmous thought patterns that are associated with certain emotions. In relation, I would propose that fascist far right political values can be promoted in a society through triggering the emotions of fear and anger, which can lead to more extremist and dichotomous thinking in people. Also I cannot think of a more far right political policy than having support for the death penalty. So to show that wanting to leave the EU is correlated with support for the death penalty could be interpreted as far right political values that are moving towards fascism. Who controls the media? Supporters of the left would argue multi-national companies. If people choose right wing political values over left wing political values this would be to the benefit of multi-national companies financialy. In other words, the advocating of certain political values has an influence on economics.

Right-wing views, opinions, or values? Holding, or agreeing with a point of view does not, necessarily, mean that one adheres to those values. I think that values are far more rigid than views, or opinions so, although I would agree that media may help to influence ones views, I think that changing, or altering ones values is far less likely, as a result of media.

I guess the question is, do these attitudes (pro death penalty, order, openness etc) change with wealth, travel, or other experiences? Who would be more likely to vote Leave, a wealthy in Sunderland or a poor in London?

A wealthy in Sunderland who lived abroad or has foreign friends, or a poor in London who lived abroad or has foreign friends?

I see some parallels here with a (controversial in my ‘profession’ of cross cultural research and training) dimension of cultural difference called “monumentalism” – coined by Michael Minkov, a Bulgarian academic and consultant and disciple of Geert Hofstede. The UK scores surprisingly high on it compared to other European cultures, but lower than the USA. Main characteristics include “pride is allowed and encouraged”, “high religiousness and importance of tradition” (cf the strong Christian faith of some Brexiteers), “acceptable to express strong views and defend them in the face of opposition” “high social polarization of opinions on current affairs”, “low educational achievement on modern subjects”, “women must not eclipse men and hurt their pride”

Excellent beginning study. Where it should go further is by noticing that “increased differentiation” goes by narrowing your sample. As you go further and further in sub-categorization, sample is narrower and narrower – giving more focused result. Once you notice that, you should study “feedback loop” between more general but wider samples (region, wealth,…) and more focused but narrower samples within (age, education, party affiliation). True answer lies in that correlation. Ex. young people vote distribution in North-East vs. one of young people in London… Without that further step you are still not at the full answer, just a hint.

You also didn’t even touch on the crucial failure of predictors (which may strike them again in the USA election and with Trump): how to interpret relatively large fraction of so-called “undecided” before the vote? As it turned out, vast numbers of “undecided” were actually for “Leave” but refused to state so in a social context. As we become more and more socially connected on the Web, there is a large fraction of people who now “hold their opinion cards tight” because of the fascist-like Web response to anything non-PC. That is the bigger hurdle for prediction than the intricate web of correlations you explore. How to deal with that properly is something that will loom large in future prediction practice.

The point about the discrepancy between predicted voting intentions and actual voting behavior is well-taken. The undecided voters often actual decide the election, as they evidently did in the case of the referendum. The prior polling inevitably would be biased toward those with stronger opinions and therefore polarized around social issues such as the death penalty.

In other words, this is a provocative piece but not a conclusive one. It will take a great deal more data and analysis to establish whether this vote reflected authoritarian attitudes or the emiseration of a lot of Britons under the Cameron administration.

A great piece. I saw the late Ian Gow MP defend his opposition to the reintroduction of the death penalty back in the late 1980s. The across-class-cutting response from his ‘hang ’em, flog ’em’ Eastbourne constituents made me realise this kind of closed personality attitude ran deep across the UK. Last week I noted public opposition to the death penalty had swung beyond 50 per cent in 2015: it is arguably Parliament’s job to protect us from unpalatable public views, unless ones party is shedding votes to UKIP. Attitudes to ‘authority’ and a desire for structure or certainty seem to underpin the Referendum result.

Very interesting blog. Figure 4 – very amused at the idea of “out” voters corresponding to BDSM (whipping sex) practitioners until I re-read.

Remain very attached to the idea that Brexiters favour sado-masochistic sex, for no good reason.

“Brexit voters, like Trump supporters”

Stopped reading right there.

You should read on. Trump supporters haven’t followed traditional classifications based on economics which were usually good predictors. It’s another example of the same phenomenon that shows it isn’t valid to attempt a vote prediction on what would’ve been a good predictor in a previous election.

Steve,

Those are profound thoughts and you raise a lot of fascinating questions around the historic tension between individual liberty and social cohesion, and whether it is possible to have more of both in the long run

Eric

Thanks Eric. Here is a very recent article dealing with values which seems to highlight that same tension.

http://www.spiked-online.com/newsite/article/what-do-leave-voters-really-think-brexit/18532#comment-2771132301

Your comment below was thought provoking and intelligent.

The Spiked article you link to, however, is neither of these.

The author writes that Leave voters wanted to “maintain sovereignty”, that “Politicians don’t care about ‘common people’”, “politics has become so stagnant that it stinks’” and that they voted Leave in the name of “Accountability and democracy”.

The author argues that, therefore, they are not racist bigots and nor are they ignorant or misinformed.

I accept that many Leave voters are not racist bigots.

But the reasons cited by the Spiked article demonstrate that they were certainly ignorant of what they were voting for, or deliberately misinformed about the pros and cons of leaving the EU.

The EU is indeed flawed and MEPs lack accountability. But this is of course equally true of Westminster politicians, as are all the other criticisms the Leavers level at the EU.

Westminster lacks accountability. Political parties ignore grassroots members (see Corbyn and Momentum). The MPs expenses scandal is just one of many recent examples of Westminster MPs placing their own interests above ‘the common people’.

The EU has actually protected citizens rights from Westminster politicians on numerous occasions. Without the EU safeguards, the ‘common people’ are actually more vulnerable to the UK’s exploitative elites.

Leave voters are right to think politicians don’t care about common people and are not sufficiently accountable, and that democracy is being undermined. But their assumption that leaving the EU will address these concerns is misplaced.

Certainly, the EU is not perfect, but it’s a damn sight better than the unregulated corporate playground that both New Labour and the Tories seem intent on creating once the EU safeguards and protections have been removed.

Hi .. I’ve been thinking along the lines of values myself and have realised that Brexit values align with a more communitarian outlook whereas Bremain values have aligned wih a more liberal outlook. This points to the dynamic between communitarianism and liberalism with the former evoking a need for commnity continuity and stability and the latter evoking a need for community change and growth.

However, the trouble with liberalism and its need for change and growth is that it is inherently ecologically and socially destructive which is a good thing if change abd growth is required but also a bad thing since it is inherently unsustainable. Liberalism, whether social and economic, is fundamentally unsustainable since if all living things had the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness then we would all starve or else be immobilised by moral constraint. This points to the fact that the sustainability of life is underpinned by life/death relationships but if not properly managed, these life/death relationships will inherently lead to unmanaged competition even if under the liberal framework of individual rights-based entitlements. This is why economic liberalism inherently leads to uncontrolled competition and the formation of monopolies of power and why social liberalism or individualism hollows out communities and leads to atomisation, alienation, identity politics and consumerism.

In this respect liberalism as a social policy tool has been a good thing in terms of deconstructing traditional communities based on entrenched patterns of patriarchy, gender inequality and class inequality but this creative destruction now needs to be rolled back in order to allow communities to recoalesce on the basis of virtue-based value systems and in particular, ones I argue that are designed to create a sustainable future that is built on a platform of community democracy and community resilience.

This is the true nature of the communitarian backlash against the eu and the globalised liberalism that it supports. Unmanaged liberalism is inherently unsustainable and destructive and whilst it is a useful ideology to deconstruct and reform communities as a social change tool, at some point it is necessary to withdraw the use of this tool in order to allow communities to reformulate around different principles. Quite ironically, with regards the eu debate, the communitarians (brexiters) were using liberalism to support their communitarian arguments whilst liberals (bremainers) were using communitarianism to support their liberal arguments.

This highlights that liberalism functions as part of a dynamic with communitarianism with the former being used to evoke change and growth wheras the latter is used to evoke continuity and stability. As such, yes the competition of liberalism is as important as the cooperation of communitarianism but each needs to be recognised for the benefits and losses they bring in order to manage social change and social continuity. In this respect, progress for its own sake and the constant social change that liberalism through individualism and self-interest brings in the form of atomized competition is damaging and unsustainable if it is not consented to by all segments of society. In effect, by trying to bring half of a society unwillingly into the liberal mold whether through eu membership or through centralised government imposition is not only undemocratic but also disrespectful of others that might wish for continuity and stability in order to build up community values through decentralised democracy and resilience. Liberalism does not allow for this regrounding of community rights because it relies upon competition or creative destruction in order to constantly change and grow society or in international order terms, it requires a willingness to cooperate in order to compete to evoke constant change and growth on a global level.

In conclusion, without recognising that liberalism is paired with communitarianism and that the two need to be applied to varying degrees according to consensus then we are not only damaging our ecological and social relations through imposed competition, which arises because liberalism is unable to reconcile the rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness when expanded to all living life-forms, but we are also damaging our relation with our self since this competitive outlook is internalised to form a divided antagonistic self. So whilst liberalism is an important socio-economic policy tool to enforce change and growth through negative rights, the inherently competitive and unsustainable effects of liberalism needs to be recognised as such and so it needs to be recognised that liberalism has as its opposite a communitarian perspective that enforces continuity and stability through positive rights and so allows communities to cooperate on a platform of democracy and resilience to formulate their own identities and values. However, if over time this continuity and stability creates entrenched inequalities, then liberalism again becomes useful to creatively destroy these entrenched inequalities. As such liberalism and its inherently competitve outcomes and communitarianism with its inherently cooperative outcomes are social policy tools which can be applied to varying degrees to create a managed dynamic between change and continuity in that if continuity (and sustainability) is required then communitarianism needs to come to the fore whereas if change (and unsustainability) is required then liberalism needs to come to the fore. At present I would argue that communitatrianism needs to come to the fore in order to ingrain communities with a sustainable development ethic based on stability which I argue would be best achieved by creating a global cooperative network of decentralised democratic communities which is underpinned by an ethos of decentralised community resilience.