Politicians often make unpopular decisions at great electoral cost, despite ever-increasing tools to gauge public opinion. Exploring three high-profile cases, interviews with decision-makers in the UK Government reveal a bias towards personal preferences over evidence of electoral damage, the misjudgement of an issue’s salience, and an assumption that voters prioritise policy outcomes. The study underscores the importance of diverse perspectives in the policy process to counteract biased reasoning.

Why do governments and elected officials take unpopular decisions? Given that they want to be re-elected, it is surprising that governments pursue policies that are at odds with the preferences of voters. Think, for example, of the UK Conservative Government allowing immigration – a policy area of greater concern to Conservative supporters – to reach historically high levels, London Mayor Sadiq Khan pursuing ULEZ despite his own party leader blaming it for the failure to win the Uxbridge by-election, or France’s President Macron pushing through pension reforms in the face of considerable opposition.

Generally, it is assumed that when governments take unpopular decisions, they do so knowing the likely electoral damage but having judged that the policy benefits in the long-term outweigh the electoral costs. In the case of the current Conservative Government and immigration, it is a consequence of increasing the routes available for migrants to plug gaps in the UK’s workforce. Khan has justified ULEZ on public health grounds, while Macron persevered with raising the state age of pensions to avoid a future black hole in France’s finances.

But is it really the case that when governments take unpopular decisions, they always do so knowingly? On the one hand, several recent studies have found that politicians and their advisers are poor at estimating levels of support for different policies. But these studies ask politicians to estimate public opinion “on the spot” as part of a survey. It is a completely different matter for governments to take a policy decision without grasping its potential unpopularity given all the resources at their disposal for measuring public opinion. Therefore, we might expect that governments would have a good grasp of public opinion before taking decisions.

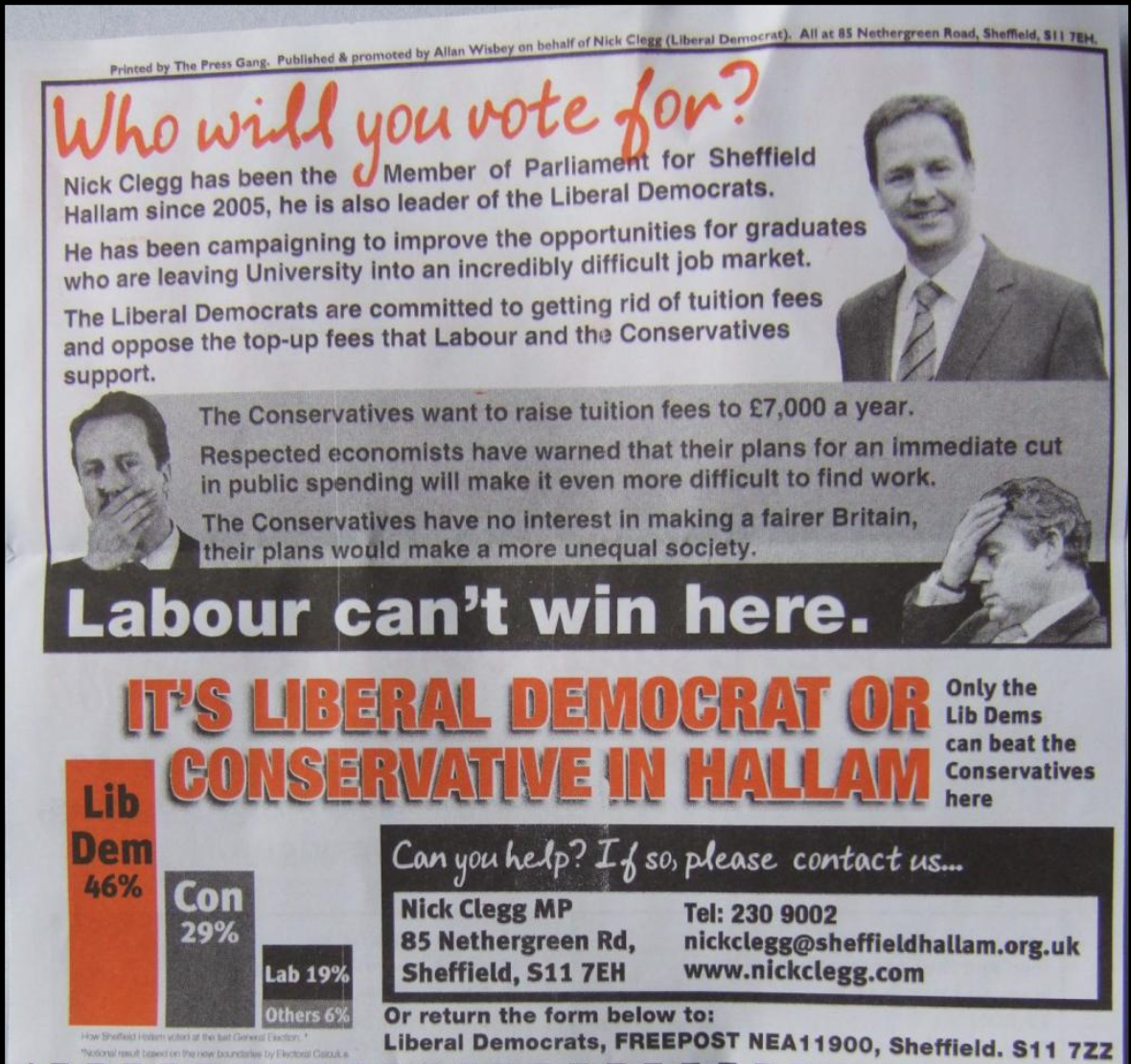

To explore further whether unpopular government decisions are always taken knowingly, my research involved interviews with 22 decision-makers involved in three cases of UK Governments taking unpopular decisions. These are 1) New Labour’s decision to allow migrants from the “A8” nations (Eastern European countries joining the EU) the right to work in the UK in 2004; 2) the Liberal Democrats’ U-turn on tuition fees from 2010; and 3) NHS reforms introduced by Conservative Health Secretary Andrew Lansley from 2010.

The interviews explored the rationale behind these decisions and how the likely electoral consequences were perceived by decision-makers at the time.

Miscalculating the electoral costs

Instead of finding that decision-makers rationally weighed up the policy and electoral benefits and costs before taking electorally damaging decisions knowingly, I found that decision-makers miscalculated the electoral costs in all three cases. As such, the results confirm recent findings that politicians and their advisers are not always good at judging public opinion.

The most common theme that emerged was “motivated reasoning” – key decision-makers wanted to pursue these policies and overlooked evidence of their potential electoral damage.

Further, in all three cases I found that politicians nonetheless had evidence that these policies were likely to be electorally costly. Labour pollsters knew that voters’ concerns about immigration extended beyond asylum, Liberal Democrats knew their opposition to tuition fees polled well among their supporters, and Conservatives knew that NHS reform was unpopular. So why did decision-makers fail to respond to this information?

From my interviews, the most common theme that emerged was “motivated reasoning” – key decision-makers wanted to pursue these policies and overlooked evidence of their potential electoral damage.

New Labour’s economic strategy was partly reliant on growing the workforce through increased immigration:

The real absolute focus from the Prime Minister downwards was on being seen to reduce the number of illegal asylum seekers coming into the UK. In a sense there wasn’t much of a focus on immigration as a problem, and therefore I think across government there was an explicit acknowledgement that immigration was important in terms of the needs of employers and we had to strike a balance, but it wasn’t regarded as the problem because the problem was asylum at that point. (Interview with former MP, 2019)

Several senior Liberal Democrats MPs had never believed in the merits of abolishing tuition fees:

There were plenty of other policies which frankly I think people in government for the Liberal Democrats believed in far, far more which we wanted to pursue. Frankly we weren’t willing to throw it all away over a policy of which numerous attempts were made to refine or ditch in the run up to the 2010 election. (Interview with former Special Adviser, 2018)

Andrew Lansley had spent years developing his proposals for NHS reforms and was determined to pursue them:

He honestly couldn’t understand why people didn’t see what he was trying to do. (Interview with former Adviser, 2019)

Decision-makers’ preferences for these policies biased them towards dismissing information that warned of the electoral consequences.

What this means for rational decision-making

Two other common themes stand out. Firstly, in all three cases there was an awareness that these decisions might prove to be unpopular, but the most significant misjudgement was as to their salience. Decision-makers reconciled themselves to taking unpopular decisions by convincing themselves that voters cared more about other issues. This demonstrates the need for future studies of politicians’ perceptual accuracy to consider how well they judge the salience of different issues.

Secondly, there was a common assumption by politicians that voters would judge policies on their outcomes. While there is some evidence that voters respond to big picture outcomes of government policy, such as economic performance, voters’ peripheral interest in politics means they are more likely to judge parties on the high-profile decisions they take. Politicians are perhaps expecting too much of voters if they think they will always join the dots to judge policies on the outcomes they eventually deliver.

Governments and political parties have enormous and ever-more sophisticated resources at their disposal to monitor public opinion. That they fail to use available information to avoid unpopular decisions demonstrates a failure to ensure that a diverse set of opinions are present during the decision-making process, which can prevent motivated reasoning affecting the rationality of their decisions.

This blog draws on the author’s published work in the journal Representation.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: LSE public events.