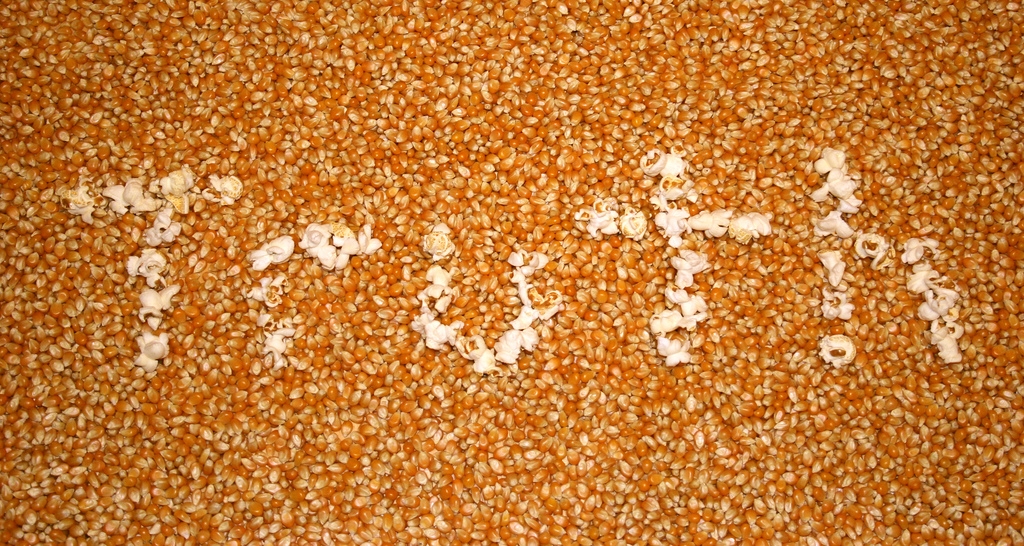

Verbal dexterity, inconsistency and ‘spin’ are part and parcel of normal politics but the exaggerations and distortions of the EU referendum campaign has led to concerns about ‘post-truth’ politics. Nicholas Allen and Sarah Birch write there is a need for someone to provide a moral lead, and argue the Committee for Standards in Public Life could play a valuable role by establishing some relevant basic markers.

Verbal dexterity, inconsistency and ‘spin’ are part and parcel of normal politics but the exaggerations and distortions of the EU referendum campaign has led to concerns about ‘post-truth’ politics. Nicholas Allen and Sarah Birch write there is a need for someone to provide a moral lead, and argue the Committee for Standards in Public Life could play a valuable role by establishing some relevant basic markers.

The recent EU referendum campaign has focused and fuelled concerns about the rise of ‘post-truth’ politics in Britain. Politicians seem readier than ever to base their campaigns on grossly distorted ‘facts’, dismiss impartial expertise and evidence, and make manifestly contradictory promises. To some extent, these concerns are nothing new. Verbal dexterity, inconsistency and ‘spin’ are part and parcel of normal politics. Coalition-building requires leaders to create and take advantage of wiggle room.

But as it has broken other things, so the referendum seems to have broken new ground in British politics. Both campaigns made exaggerated and misleading pronouncements, with Vote Leave’s claims about imminent Turkish membership and the £350-million-a-week of EU membership being perhaps the most blatant.

Then there was the case of Michael Gove, who, during a televised debate, dismissed his leadership ambition by emphasising his unfitness for office and declared he was ‘absolutely not’ going to stand in any future Conservative leadership campaign. There was no ambiguity in Gove’s declaration, no wiggle room. Many journalists noted the subsequent U-turn, when Gove decided to stand after all, but then they moved on.

Again, it is important to recognise, first, that politicians have always stretched the meaning of words; and, second, that they sometimes need do so in pursuit of a higher goal. Thus Abraham Lincoln disingenuously denied knowledge of a Confederate peace delegation in 1865 when news of its travelling to Washington, DC threatened passage of the Thirteenth Amendment.

Yet, current trends, first identified in the context of US politics and more recently in the context of British politics, risk stretching beyond breaking-point a basic commitment to truth and honesty that is essential for liberal democracy. Without it, citizens cannot hope to achieve ‘enlightened understanding’ and learn about what best serve their interests, one of five criteria identified by Robert Dahl that define modern democratic government. Someone in government, or at least in officialdom, needs to take note. Someone needs to provide a moral lead.

There already exists in Britain a body that should investigate these developments: the Committee on Standards in Public Life (CSPL). The CSPL was established in 1994 by the then prime minister John Major to examine contemporary ‘concerns about standards of conduct of all holders of public office’ and to make recommendations needed ‘to ensure the highest standards of probity in public life.’ It was initially known as the Nolan Committee, after its first chairman, Lord Nolan, a law lord.

Unlike previous commissions and tribunals established to consider the integrity of public life, the Nolan Committee was different. It would be a standing body. In the climate of the times, its initial incarnation and proposals carried considerable political weight.

Much of the CSPL’s early work reflected the concerns that prompted its creation, in particular allegations that some MPs and others in public life were benefiting financially from their office and resolving conflicts of interest to their or their political party’s advantage. Indeed, the whole notion of standards in public life was generally construed in these narrow terms. In 1997, when the CSPL’s remit was later extended to party-funding arrangements, it was very much within this limited understanding, with an emphasis on the influence wielded by wealthy benefactors.

As other commentators have noted, the CSPL has arguably lost its way in recent years. Rather than addressing bigger questions of public ethics, it has increasingly focused on routine aspects of public-sector integrity. At the same time, the CSPL’s resources and remit have been constrained by successive governments, and its political weight has been much reduced.

All of these developments are unfortunate. There is still a need for some body to keep an eye on the bigger picture of British political ethics. As a recent review of the CSPL noted, ‘The Committee should keep a watching brief on broader ethical issues’. The apparent rise of ‘post-truth’ politics undoubtedly raises them.

As successive CSPL surveys have noted, public concerns about politicians’ use of words is the elephant in the room of British standards in public life. As our own research has shown, citizens’ conceptions of ethics and integrity in politics extend beyond a narrow concern about politicians’ misuse of office for material gain and conflicts of interest. It embraces the words that politicians use and the promises they make.

While there are still ethical failings in British public life relating to politicians’ and others’ use of public office for material gain, there are also clearly ethical failings in terms of the claims and pronouncements that are made in the course of political campaigning. Such failings relate to the common-or-garden conceptions of honesty and integrity that most citizens have in mind.

As noted, words will always be misused and the truth stretched in the pursuit of political goals, and we are not so naïve as to think that this can or should be stopped entirely. But the time has surely come for our commitment to standards in public life to reflect better the understandings that most people have of it.

In this spirit, the CSPL could provide a valuable lead by establishing some relevant basic markers. These might include: the extent to which British public life has become corrupted by a ‘post-truth’ mindset; what we might reasonably expect from politicians and campaigners in terms of their verbal integrity; and what might be done to promote such standards.

If the CSPL lacks the capacity to conduct such an inquiry, others need to help it. For some of those involved in its creation, the CSPL was expected to provide advice as needed, partly on the model of the now defunct Security Commission. Amid the many demands on her time, the new prime minister Theresa May would do British democracy a service by inviting and empowering the CSPL to provide her with advice relevant to contemporary ethical concerns.

Morality in politics needs to come from somewhere. The CSPL is charged with overseeing standards in public life. The new prime minister should give it the resources and remit to do just this.

__

Note: This article was originally published on Democratic Audit.

About the Authors

Nicholas Allen is a Reader in the Department of Politics and International Relations at Royal Holloway, University of London.

Nicholas Allen is a Reader in the Department of Politics and International Relations at Royal Holloway, University of London.

Sarah Birch is Professor of Comparative Politics in the School of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Glasgow.

Sarah Birch is Professor of Comparative Politics in the School of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Glasgow.

There is an EDM about an office for monitoring political campaigns. If the CSPL had a higher public profile then such EDMs shouldn’t be necessary. MP’s should’ve known about this organisation and would’ve informed the petitioners.

With exception of PM on Radio 4, I didn’t find any other debates stimulating and the snapshots I saw of the TV debates didn’t help me create the opinion other than MP’s ‘slagging’ each other about their abilities. As the Leave MPs didn’t provide a plan for Brexit then the votes made by people were based upon their own opinions which were probably not influenced by MPs. MPs just used simple messages which encouraged people to vote Brexit. The same with Remain campaigners. Their messages were of the same level and therefore not likely to challenge leavers to remain.

No way is it misleading to say that we could spend £350-million-a-week differently after BREXIT. This figure is on the UK Treasury website as the money that the EU decides how to spend – some of which the UK Gov spends (~£135m/wk).

Of course, most the EU spending inside UK is on CAP, Fisheries, & poor regions, which will need to be continued to a large extent.But that still leaves a lot that can be spent on something else.

This illustrates the main problem that it’s all so very complicated. As people simplify their message, it can be badly misunderstood. But calling it lies and falsehoods is wrong.

Politics has been this way for decades, certainly since before I was born in the ‘70s. A binary referendum will always appear to exacerbate it because unlike a general election where both sides mildly lie, embellish and massage facts about everything there is a focus on very specific things. This tends to make the lying somewhat more obvious.

Additionally, very few of the electorate ever believed there would be a new NHS hospital each week or cares whether it is £350m, £275m or £50m each week. Your colleagues’ excellent blog (https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/explaining-brexit/) bears this out. The electorate were not swayed much by these kinds of argument (they are mere barnacles to use a Lynton Crosby’ism) –the broad feeling was that Brits wanted out and like sentiment before general elections the campaigning efforts rarely have a significant impact.

Finally, this notion of ‘Post factual’ politics is the biggest load of sour grapes going and is grossly misleading in itself. It wasn’t that people did not accept the facts presented to them it’s just they were outside their decision making criteria. Using the IMF, OECD etc as political tools to deliver ‘facts’ will nearly always fail because there is no public trust in those institutions and they tend to talk in averages and generalities, which most people instantly identify as being abstract and speculative.

It may be frustrating but scepticism is at the root of why democracy has worked over the centuries.