Martha Kirby highlights how the proportion of the public mentioning the environment as one of Britain’s most important problems has fluctuated in recent decades and links the recent striking rise with protest activity.

Martha Kirby highlights how the proportion of the public mentioning the environment as one of Britain’s most important problems has fluctuated in recent decades and links the recent striking rise with protest activity.

The climate crisis has been high on the public and political agenda in recent years. Shortly after the last general election, and prior to the pandemic, 25% of the public recalled the environment as a top issue facing the country – the highest level since 1990. More recently, in the month that COP26 negotiations took place, this stood at 40%. These elevated levels of concern have important implications for future political discourse and, given that any substantive policy move will require widespread societal change, it is vital to better understand public attitudes on environmental issues and support for mitigation measures. But despite this, our knowledge of how and, more importantly, why environmental public opinion has changed over time in Britain remains relatively limited.

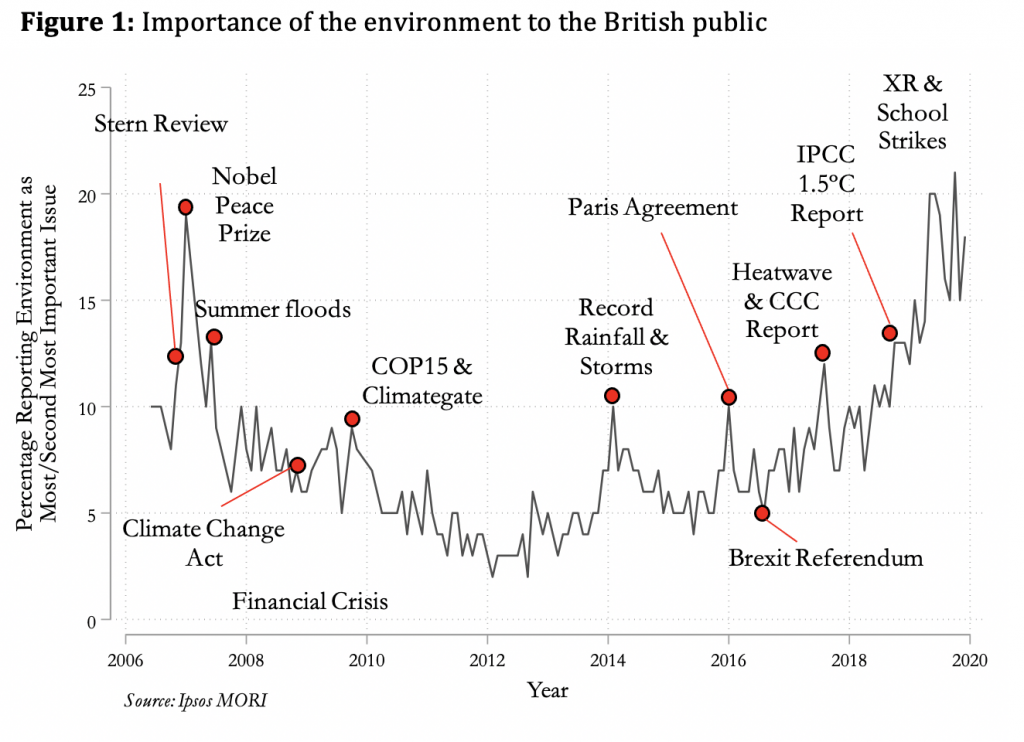

In fact, while climate change has been in the public spotlight in recent years, prior to this, the perceived importance of the environment to the public has fluctuated dramatically over time and before 2012, was in decline. This is despite the objective threat and seriousness of climate change (e.g. rising global temperatures and CO2 levels, as well as scientific consensus) having gone up year-on-year. So, what explains these changes over time and, given that the evidence for climate change has not changed drastically, where did this newfound public attention come from?

My recent article looked at why these changes occur, by analysing monthly trends in the importance of the environment to the British public between 2006-2019 and simultaneously considering a range of factors which may influence levels of public attention to the issue. Given that recent changes co-occurred with global environmental movements such as Extinction Rebellion and School Strikes for Climate, did these play a role in driving attention to the issue, or were these events merely a product of rising concern? Is public attention a function of media coverage of the issue, or influenced by the extent to which it is prominent in political debate? As peaks in attention can be linked with occurrences of a range of environmental, political, and cultural events, are these successful in drawing, and more importantly maintaining, attention to the issue? These are some questions that the article considered. The results of the study have important implications in terms of public environmental perceptions, although by and large, few variables are able to consistently predict change over time. Changing CO2 levels, natural disasters, and political events such as United Nations Climate Change Conferences may influence media coverage of climate change, but are not able to consistently predict levels of public attention to the issue, despite being linked with spikes in some instances (as shown in Figure 1). This suggests that the effects of these factors either do not impact public attention enough for it to be sustained past the same month, or that they are not a consistent predictor over time.

The results of the study have important implications in terms of public environmental perceptions, although by and large, few variables are able to consistently predict change over time. Changing CO2 levels, natural disasters, and political events such as United Nations Climate Change Conferences may influence media coverage of climate change, but are not able to consistently predict levels of public attention to the issue, despite being linked with spikes in some instances (as shown in Figure 1). This suggests that the effects of these factors either do not impact public attention enough for it to be sustained past the same month, or that they are not a consistent predictor over time.

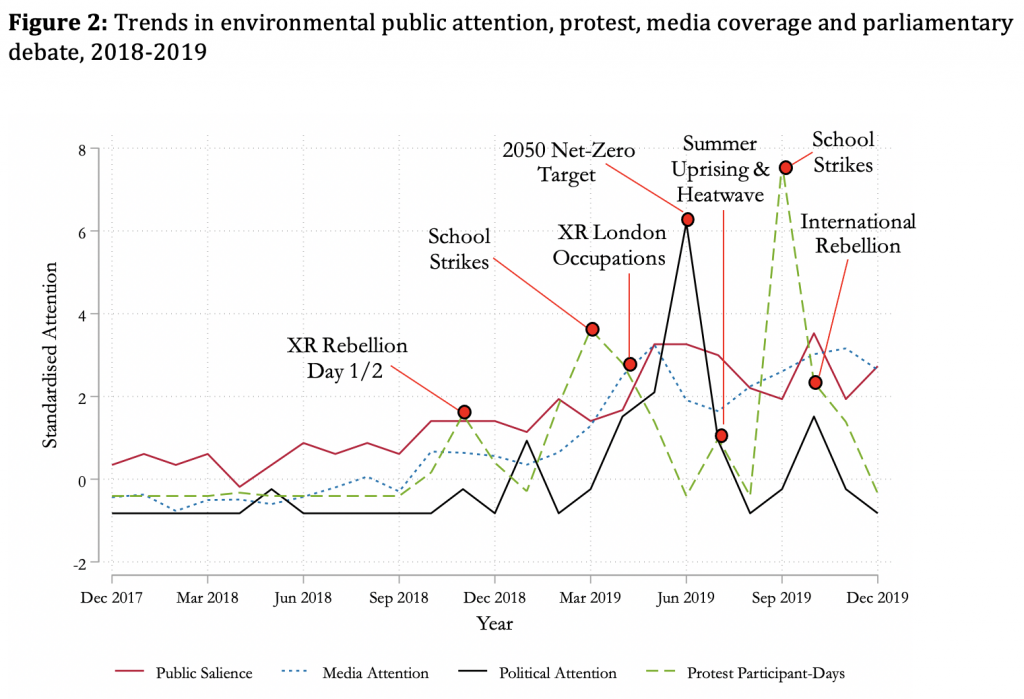

One of the key findings, however, is that the spike in public attention to the environment in recent years can be linked to protest activity. Protest can be predicted by prior levels of public attention to the environment but a surge in protest levels also leads to increased public attention in the following months. This effect is largely driven by recent protest, which indicates it played a role in recent rise in public concern. Another finding of note is that, contrary to the supposed effectiveness of civil disobedience and disruption that Extinction Rebellion aim for, findings suggest it is the scale of recent protest, rather than its disruptiveness (measured by the number of arrests), that seems to have shaped public opinion.

The article also indicates that if politicians act on climate change this may result in adjusted levels of public concern, as increased parliamentary debate on climate change is found be associated with less people prioritising the environment as an important issue. This response is largely being driven by the changes which occurred following the environmental legislation introduced in June 2019, which aims for net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. However, this speaks to a broader debate that net-zero legislation might not be constructive as it not only distracts from attending to policy action now but may also make the general public less concerned about the environment.

Although media coverage of the climate crisis has also been heightened in recent years, looking at the period as a whole, findings suggest that media is not playing a significant role in driving increased attention to the environment at the monthly level. Instead, the number of media articles on climate change can be predicted by changes in public demand and occurrence of protest in the preceding months.

Overall, this has important implications for our understanding of the dynamics of a major policy issue, and how we understand public opinion more generally. While it is commonly discussed that protest could be of importance, with environmental protest it is hard, if not impossible, to point to other studies to confirm this. This research shows that as protest is becoming increasingly widespread, its role in shaping public attention and the political process more broadly in years to come should not be discounted.

_____________________

Note: the above draws on the author’s published work in The British Journal of Politics and International Relations.

Martha Kirby is a researcher at Nuffield College, University of Oxford.

Martha Kirby is a researcher at Nuffield College, University of Oxford.

Photo by Ronan Furuta on Unsplash.