It is no secret that higher teacher quality translates into higher educational outcomes, but how can the UK attract the best and brightest to the profession? Peter Dolton and Oscar Marcenaro-Gutierrez examine the enormous variation in teachers’ pay across OECD countries and find evidence that if teachers are better paid and higher up the national income distribution, there is likely to be an improvement in pupil performance.

It is no secret that higher teacher quality translates into higher educational outcomes, but how can the UK attract the best and brightest to the profession? Peter Dolton and Oscar Marcenaro-Gutierrez examine the enormous variation in teachers’ pay across OECD countries and find evidence that if teachers are better paid and higher up the national income distribution, there is likely to be an improvement in pupil performance.

Why do teachers in Switzerland earn four times what teachers in Israel earn? Why are teachers in South Korea paid at the 78th percentile of their country’s income distribution whereas those in the United States are paid at only the 49th percentile? And do these massive variations in the way different countries treat their teachers matter for the outcomes of their pupils? Answers to these questions are at the heart of the educational policy debate and we can learn a lot about the relationship between teacher quality and pupil outcomes from cross-national comparisons.

The issue is especially relevant in the context of pressures to reduce public spending. Most countries devote a sizeable proportion of their budgets to education – and around 70 per cent of that money goes on teacher salaries. Our research considers the determinants of teacher salaries across OECD countries and examines the relationship between the real and relative levels of teacher remuneration and the measured performance of secondary school pupils over the last fifteen years.

There are two potential explanations as to why teachers’ pay may be causally linked to pupil outcomes. The first is that higher pay will attract more able graduates into the profession. As the potential supply of teachers rises because of the higher pay on offer, entry into teaching as a profession will become more competitive. This in turn will mean that the average ability of those entering the job will rise. Once recruited, higher relative pay and/or more performance-related pay may provide teachers with stronger incentives to improve their pupils’ educational outcomes.

The second mechanism is more subtle– namely that improving teachers’ pay improves their standing in a country’s income distribution and hence the national status of teaching as a profession. As a result of this higher status, more young people will want to become teachers. This in turn makes teaching a more selective profession and hence facilitates the recruitment of more able individuals. Higher status and higher pay are invariably linked but the two can provide separate driving forces to engineer better recruits to the profession. The key hypothesis is that better pay for teachers will attract higher quality graduates into the profession and that this will improve pupil performance.

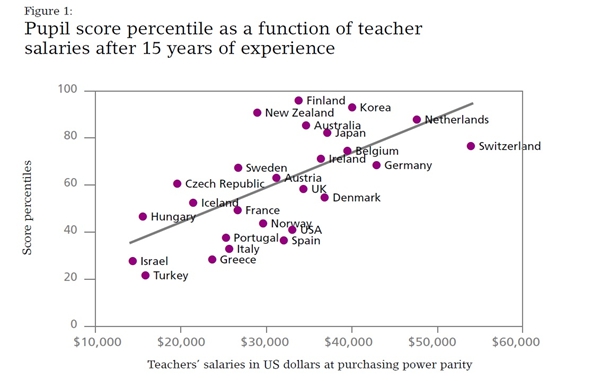

Based on the OECD’s annual ‘Education at a Glance’ reports (the most comprehensive sources of comparative information about teachers in different countries), Figure 1 above provides an insight into the relationship between teacher salaries and pupil outcomes, showing a clear statistical association between higher relative teachers’ pay and higher standardised pupil scores across countries. Our research with aggregate country data supports the hypothesis that higher pay leads to improved pupil performance. As an indication of the relative size of this effect, we find that a 10 per cent increase in teachers’ pay would give rise to a 5-10 per cent increase in pupil performance. Likewise, a 5 per cent increase in the relative position of teachers in the income distribution would increase pupil performance by around 5-10 per cent.

What are the policy implications of these findings for the UK? Most obviously, if the government is concerned with educational outcomes, then it should be aware that the quality of its teachers is of fundamental importance. We suggest that the route to hiring teachers from higher up the ability distribution is to pay them at a higher point in the country’s income distribution. How could this be achieved?

A country with a stock of low quality teachers cannot simply raise the pay of all teachers immediately and expect the quality of teaching to improve. The existing stock of teachers would clearly have an incentive to appropriate these economic rents with no responsibility to become better teachers. And while the quality of new recruits to the profession would rise as a result of this upward shift in relative pay, it would take a long time – 30 or so years – to change the quality of the whole stock of teachers.

The answer then must be to consider how teacher quality can be raised gradually. If the government were to ratchet up starting pay, this would secure better quality new teachers. But improving the stock of existing teachers would require continued professional development and in-service training and/or attempting to fire the worst teachers. Such policy measures are not within the scope of this study, but there is a wealth of research evidence about them as possible remedies to improve the existing stock of teachers. One solution is to provide an incentive mechanism for existing teachers to improve quality by paying them according to the percentile performance (in value added terms) of their pupils. Another possible solution is to increase the rate at which teachers’ pay rises with their level of experience.

Another dimension of the problem is the time scale over which any improvement in pupil outcomes is sought. If replacing existing teachers with ones of higher quality would take too long, then a quicker fix might be to reduce the pupil/teacher ratio or increase pupil contact hours by simply employing more teachers from the pool of inactive teachers. Our analysis finds a clear trade-off between pupil/teacher ratios and teachers’ pay across countries – that is, countries do not necessarily have to pay higher salaries to secure better pupil outcomes. But if a country is not prepared to pay teachers relatively well, then it will have to go a long way down the road of reducing class sizes to compensate them – in short, governments and educational administrators need to know that there is ‘no free lunch’ here.

The policy implications of our findings are relevant to the recruitment of teachers and the improvement of educational standards. The link we find between teacher quality and high educational standards has logical implications for any government’s commitment to recruit, retain and reward good teachers. In this regard, it seems that increasing teacher salaries (and the speed at which they can reach higher pay levels within a particular pay structure) will help schools to recruit and retain the higher ability teachers that schools need to offer all pupils a high quality education.

This is a shortened version of an article which first appeared in the October 2011 edition of CentrePoint, available online here.

Please read our comments policy before posting.

________________________________________________

About the authors

Oscar Marcenaro-Gutierrez – University of Malaga

Oscar Marcenaro-Gutierrez – University of Malaga

Oscar Marcenaro-Gutierrez is assistant professor at the Department of Statistics and Econometrics of the University of Malaga and Senior Research Fellow at the Fundacion Centro de Estudios Andaluces. He has been working on projects focused on economics of education and labour economics.

_

Peter Dolton – Royal Holloway College, University of London

Peter Dolton – Royal Holloway College, University of London

Peter Dolton is a Professor of Economics at Royal Holloway College,University of London and Senior Research Fellow at the London School of Economics’ Centre for Economic Performance’s education and skills programme. His research interests are in the economics of education, the labour market and applied econometrics. He has published over 100 articles, mainly in leading economics journals.

The correlation is, in my view, farcical. Statistics like this ignore the very complexity of context. A schooling system is composed of many facets, one of which is who governments think teachers are. Are they technicists who ‘deliver’ a programme publishers determine, or are they developers of curriculum adapted to meet the needs of learners within individual classrooms? Certainly in New Zealand – up there with Finland – we are a unionised profession, so equating unionism with poor performance is a fallacy in our context. Perhaps it’s more to do with treating teachers as PROFESSIONALS who know what they’re doing and can provide feedback/feedforward to learners, or who aren’t slaves to tests. Perhaps these might have something to do with it? As soon as monetary reward is tied to exam success, you are more likely to get teaching to the test, rather than deep, satisfying learning that leads to creative and critical thinkers.

What interests me in this are the outliers at the top of the score percentile axis. New Zealand, Finaland and Australia do not pay their teachers very highly yet their students are the best performers. There must be some other factors at play in determining student performance.

Great article! Actually there is a faster way to speed up the improvement in quality of teachers. Raise salaries immediately, but also reduce restrictions on performance based firing.

This way, teachers must up their game immediately or risk being fired and a more talented teacher put in their place, and would yield to a faster increase in teacher quality.

"tokenadult" over at Hacker News, has very completely summed up why this study shows only corollary results, and shouldn’t be used as a basis for forming policy.

Have you done a similiar analysis between teacher salary and NAEP scores for US states? Would be a nice way to confirm the result. You could adjust the NAEP score based on demographics, either low-income or ethnicity.

You touch on an interesting point when you said: Why are teachers in South Korea paid at the 78th percentile of their country’s income distribution whereas those in United States are paid at only the 49th percentile?

In fact, wouldn’t income paid as percentile of national income be a better value to chart on the x-axis; as people tend to care more about their income relative to others, than any absolute amount?

Also, I’m curious how you handled differences in taxation and pensions. Teachers in the US have relatively generous pensions, especially compared to the population at large; with some estimates being that this benefit can be worth as much as $20,000/yr.

Where do those teachers’ pay figures come from? Does Israel really pay its teachers less than Turkey or Hungary? Do teachers in the UK really have pay which has them better housed than in the US? Or are those figures just made up? Something is wrong somewhere.

I think some of these data are misleading a bit. Instead of analyzing outcomes versus “Teachers salary in U.S. dollars,” you should be analyzing outcomes versus overall compensation per hour worked (with pension and health benefits included). For example South Korea has near year-round schooling, so I’d imagine their teacher compensation might actually be lower than the U.S. per hour.

I do not think there are many people in the U.S. who would disagree, a priori, with the hypothesis that if you recruit more capable and educated individuals into the teaching profession via higher salary incentives, that the educational system would improve. But in the U.S. we have a public education system completely owned by public labor unions, who barter for more pay for the same (or less) time worked, and continue to ask for higher and higher health and pension benefits.

Give us a system without unionized labor, where underperforming teachers can be fired at will, where health benefits are equivalent to the private sector, where pensions are transitioned to 401k plans with employer-matches equivalaent to the private sector, and with bonus compensation for performance, and then we can talk about raising starting salaries.

Your response rests on the assumption that there are more capable people out there who can actually run a classroom. I’d like to see evidence of that.

And your last paragraph has no solutions that will improve teacher performance, with the exception of dismissing (though not “at will”) underperforming teachers. Benefit pay is relevant only as a total compensation mechanism and incentive pay will not work.

Of course there are more capable teachers. It has been proven at by people like Dave Levin of Kipp and Eva Moskowitz at Success Academy Charter Network. Higher compensation must be tied to better results.

Plato

1. Twenty-two states in the US are right-to-work states. Believe me teachers unions have very little power in these states. People who employ the same old negative and ubiquitous anti-union rhetoric without seriously looking at the reality of the impact of unions on education (or any other profession, for that matter) are not only tiresome but show a lack of reasoning. I want to see the evidence of their statements.

2. Teachers do not choose either the number of days they work, or the number of hours. They are salaried professionals who work for the public. It is the people of the US who do not wish to change the number of days their children are in school.

3. If you want to compare total compensation packages of teachers (salary plus benefits) then this is the methodology which must be used to compare all employees. Benefits certainly have monetary value; however, take-home pay is what is used to pay the bills. Also, I would like to see a factual analysis of these supposed super benefits which teachers have. Please compare the benefits of teachers to that of other professionals. I’m not sure what you are referring to, but anecdotal “evidence” is not appropriate. I challenge you to find the numbers which prove your statements. In my experience, none of what you say is true. Why are your anecdotes more accurate than mine?

4. Teachers in the US today are able to be fired as long as administrators do their job. It is simply a process of proper evaluation. Most employees at the professional level expect to be evaluated upon their work performance, teachers expect the same. If the evaluation is poor and the professional person does not make appropriate changes, they can be non-renewed for cause. There is a process here which most human resource people realize is set up to protect both employer and employee. Proper use of that process is imperative to improve educators, including administration and support staff as well as teachers. Educators welcome such efforts.