Peter Allen applies LA Paul’s idea of transformative experience to political life. He explains that many decisions in politics – whether to run for office, whom to vote for, or those that politicians make daily – can be personally or collectively transformative. Without acknowledging that uncertainty is part of the process, and if we try to decide rationally, we might be doomed to fail.

Peter Allen applies LA Paul’s idea of transformative experience to political life. He explains that many decisions in politics – whether to run for office, whom to vote for, or those that politicians make daily – can be personally or collectively transformative. Without acknowledging that uncertainty is part of the process, and if we try to decide rationally, we might be doomed to fail.

As we live our lives, we are often faced with big decisions. Should we try to have a child? Should we take that job? Should we move to that country? We want to make these decisions carefully and rationally. The traditional way that we are encouraged to do this is to put ourselves in the shoes of our future selves – what will it be like to be us if we choose one option over the other? Having engaged in this act of imaginative projection, we then choose the outcome we liked the most.

But what if this common approach doesn’t always work, especially for those major life decisions where we need it most? What if the very nature of some experiences about which we are deciding means that we can’t use this method – the normative rational decision model – to make our choice? Recently, the philosopher LA Paul has argued that we encounter choices that confound the rational approach more often than we think. She identifies a category of fairly common experiences as being ‘transformative’ – they are epistemically transformative, introducing us to subjective knowledge about the experience that can only come from undergoing it, and personally transformative, with the experience changing our subjective preferences about ourselves and the world around us.

When we are faced with a choice about a transformative experience, the traditional approach described above fails us: we can’t accurately imagine what it will be like to undergo the experience without having done so, and we don’t know that our preferences at the time of choosing will survive the experience either. To put it another way, we don’t truly know what we are potentially getting ourselves involved in, and we also have no idea that our future self will share our current views about who we are and the world we live in.

Why does this matter for political life? In my recent paper in The Journal of Political Philosophy, I argue that there are many transformative experiences in and around politics that, taken together, should affect the way we think about the role of certainty in political life.

Imagine that you are considering putting yourself forward as a candidate for political office. You project forward and imagine what it might be like. You’ll figure you’ll be busy, sure. You’ll have to meet a lot of voters. You might need to travel a lot more if you win. And so on. It seems like you might be able to imagine what it will be like. But it another sense, you really have no idea: what will it feel like to be viewed by others in this new light, as an elected politician? What will it really feel like to vote on life or death issues? Without actually doing these things and becoming that person, it is hard to say. Similarly, it seems equally hard to know that, come the time you eventually enter elected office, your preferences regarding various policies and initiatives won’t have shifted during the process of getting there.

Aside from those affecting elected politicians, there are also transformative experiences lurking in what seem to be more mundane aspects of political life. Take voters, for whom the possibility of switching allegiance from one party to another is not simply an abstract mathematical calculation, but is instead bound up with deeper questions of identity and belonging. For example, if my family has always voted Labour, and it is a key part of our shared lore, then my choosing to give my vote to another party may prove transformative.

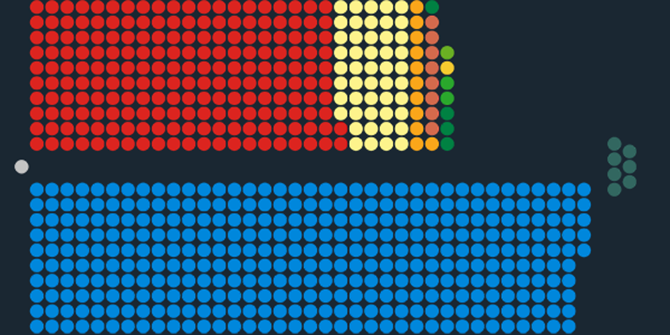

On a grander scale, what of those instances where voters as a group are faced with transformative choices at the ballot box? These cases, which Eric Schliesser has termed collective transformative experiences, might be seen to include the referendum on UK membership of the European Union. Brexit bears many of the hallmarks of a transformative experience. As is becoming increasingly clear, we had little idea what the process following a vote in favour of Brexit was going to be like until we went through it, resulting in a kind of epistemic transformation. On an individual and collective level, the identity of the UK in relation to the rest of the world has also transformed in ways that were unclear before the process of Brexit got underway, something akin to a personal transformation.

Aside from these cases where voters make transformative choices as a group, collective transformative experiences can also be seen to come about as the result of the decisions of individual political actors. When policymakers deal with issues like climate change, for example, they are taking transformative decisions not only on behalf of their citizenry, but also on their own behalf – in both respects, the decision is epistemically and personally transformative.

So, where does this leave us? How are we to proceed with making decisions of this kind as we go about our political lives? Thinking about how we view politicians and policymakers, it does seem to suggest that they should be given greater flexibility, and treated with more compassion, as they move forward with policy decisions. More generally, it raises questions about the relationship between voters and those they elect to office, and congruence between their respective views at various points in the electoral process.

Considering what this means for us as individuals, though, I am more optimistic. Rather than troubling us, I think that acknowledging the existence of transformative experiences can prove liberating, potentially widening political participation beyond those who feel themselves to be qualified (and capable of certainty) and encouraging innovative thinking in the political sphere. Accepting that we don’t always know what is going to happen, and that this isn’t some failing on our part, means that when we choose in transformative cases, we ultimately have to choose uncertainty. As LA Paul puts it; ‘’when making these kinds of transformative decisions…you choose to become a certain type of person and to live your life a certain way, but you don’t choose it because you know what it will be like—you choose it in order to discover who you’ll become.’

_______

Note: the above draws on the author’s article, published in the Journal of Political Philosophy.

Peter Allen is Reader in Comparative Politics at the University of Bath.

Peter Allen is Reader in Comparative Politics at the University of Bath.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Pixabay/Public Domain.

Good, I also want to know why the policy makers have not been able to make rational policies?