Using estimates from the Labour Force Survey, Alan Manning and Rebecca Rose fill in some of the gaps of the government’s Sewell Report on race and ethnic disparities. Comparing disparities in pay, employment, and unemployment among different ethnic groups in the UK, they show that there has been little change over the past 25 years. Indeed, for black, Pakistani, and Bangladeshi men and women, pay gaps with white men and women have widened.

Using estimates from the Labour Force Survey, Alan Manning and Rebecca Rose fill in some of the gaps of the government’s Sewell Report on race and ethnic disparities. Comparing disparities in pay, employment, and unemployment among different ethnic groups in the UK, they show that there has been little change over the past 25 years. Indeed, for black, Pakistani, and Bangladeshi men and women, pay gaps with white men and women have widened.

Part of the report of the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities (known as the Sewell Report) is about how ethnic minorities fare in the UK labour market compared to white people and how disparities in pay, employment, and unemployment have changed over time. The report gives the impression that disparities are falling over time. For example, on page 110, it refers to an ‘overall convergence story on employment and pay’, but does not present all the available evidence to justify that conclusion.

What has happened to pay differentials by ethnicity?

The Sewell Report contains some information on current pay differentials by ethnicity that comes from an Office for National Statistics (ONS) publication, but not on how these differentials have changed over time. Yet these trends are crucial if we are to evaluate a claim that the labour market is now a more hospitable place for ethnic minorities. The report presents some data on unadjusted (or raw) pay differentials and also after adjusting for a set of characteristics that are important in determining pay. Adjustment is critical for having a meaningful comparison. For example, ethnic minorities are more likely to live in London (where wages are higher) than the white population. The unadjusted pay differential looks smaller than it really is if one does not take this into account.

While some adjustment is necessary, there is less agreement about what to control for. To give an example, if occupation is controlled for, one is estimating pay differentials within occupations. But an important part of the pay penalty may be over-representation in low-paying jobs, which controlling for occupation would miss.

A complete analysis would look at different sets of control variables as seeing how pay differentials vary with the variables used provides important clues about the sources of those pay differentials. We do not do that here. We control for personal characteristics (age, gender, qualifications, region, marital status, dependent children) but not job characteristics. This will provide estimates of pay differentials within education groups when access to education may also be important. But that is something that happens outside the labour market and we are interested in how the labour market rewards qualifications.

We restrict our sample to those born in the UK, and consider the period from 1995 to 2019 inclusive. The ethnicity question in the Labour Force Survey has changed over time, becoming more detailed. But to look at long-term trends, we need to reduce to a set of definitions that have been used throughout the period: these are white, black, Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi and Chinese. Some of these groups are themselves very heterogeneous, but the available data do not allow us to dig deeper.

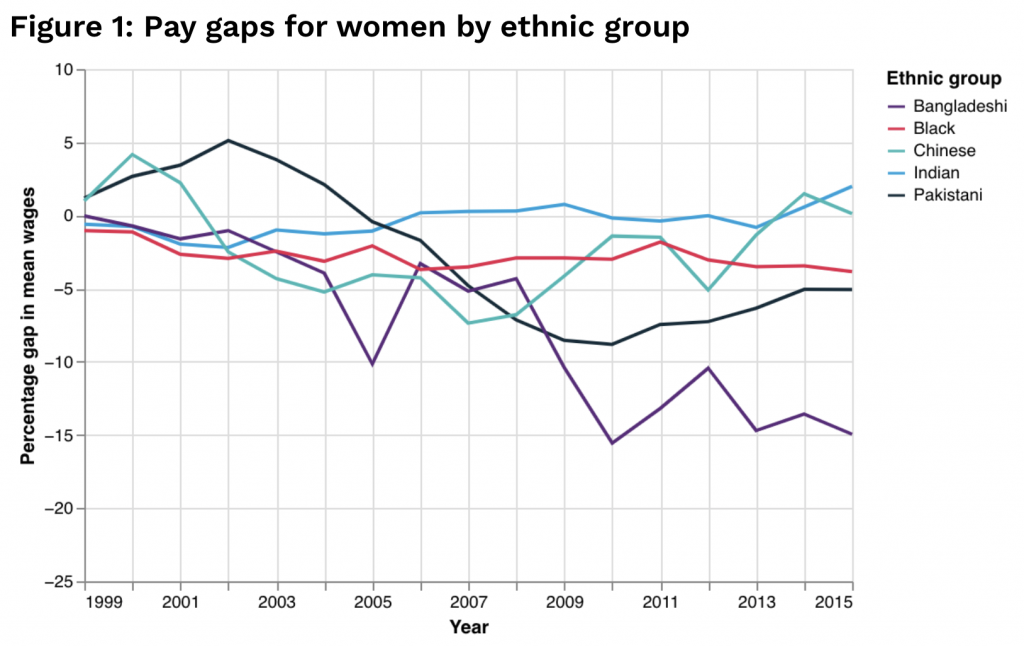

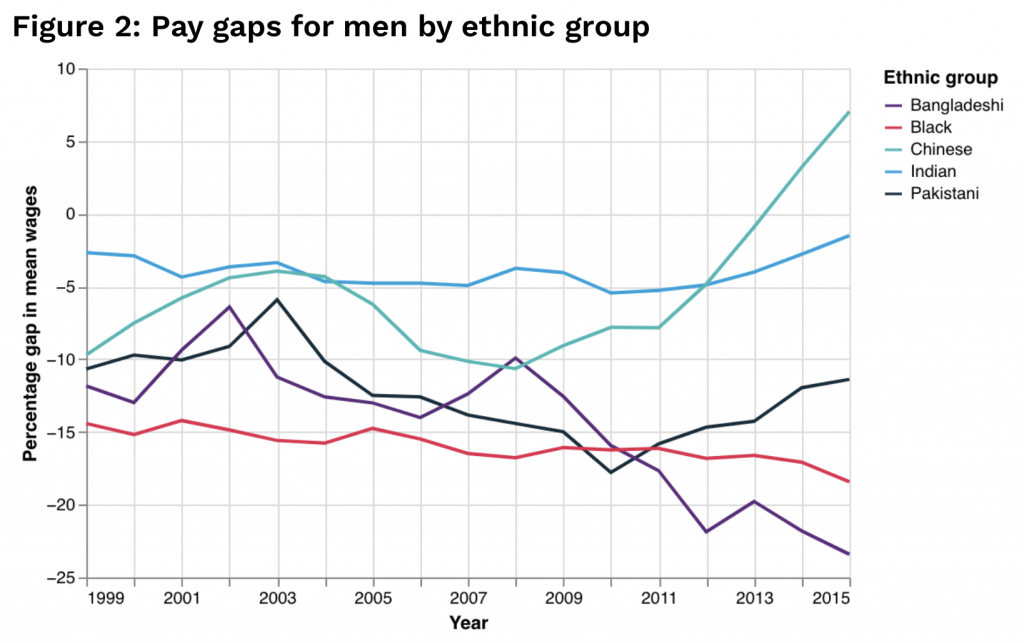

Figure 1 shows how the differentials in hourly pay between ethnic minorities and whites have evolved over time. To make any trend clearer, we report nine-year rolling samples so, for example, the year labelled 2015 is for the years from 2011 to 2019 inclusive. We do separate analysis for women (reported in Figure 1) and men (reported in Figure 2).

Chinese and Indian women have similar levels of pay to white women but always have done for the past 25 years. Their situation has not improved. Black, Pakistani and Bangladeshi women have lower pay and for all three groups, the pay gap is bigger now than 25 years ago though only slightly so for black women. For Bangladeshi women, the pay penalty has increased a lot. There are many possible reasons for this; one should not jump to conclusions about the causes.

Figure 2 shows that the pay gaps between ethnic minority and white men are generally larger than for women – very dramatically so in the case of black men. For Chinese men, the pay differential has reduced so that they now earn more than white men even after adjusting for characteristics. But the other groups earn less and the pay differentials have widened.

It is clear there is no evidence for pay gaps being smaller for ethnic minorities now than they were 25 years ago, contrary to the impression given by the Sewell Report.

What has happened to rates of employment and unemployment?

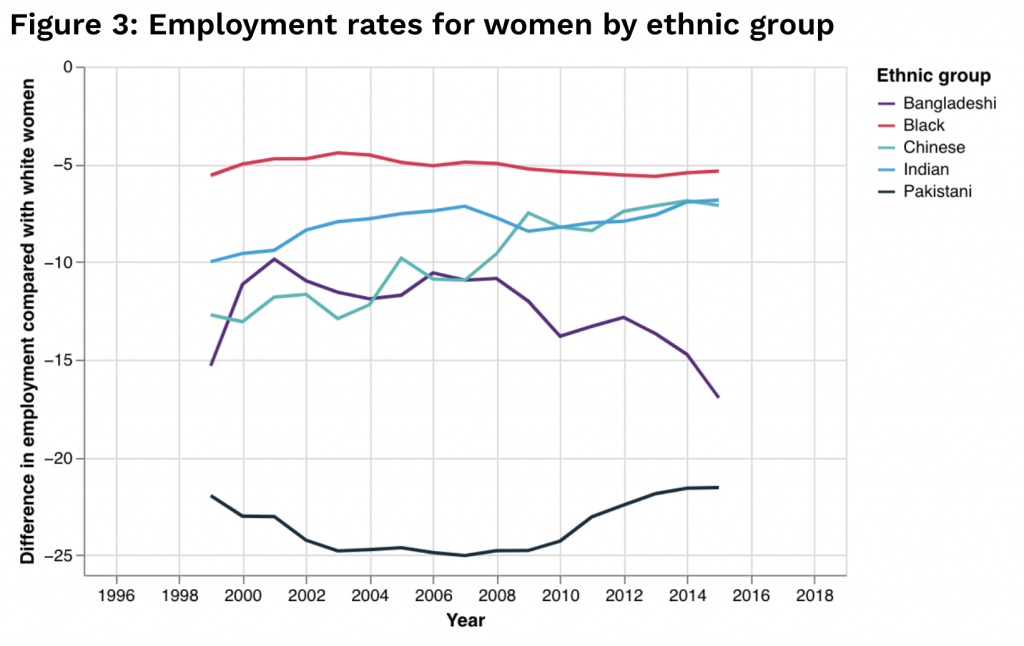

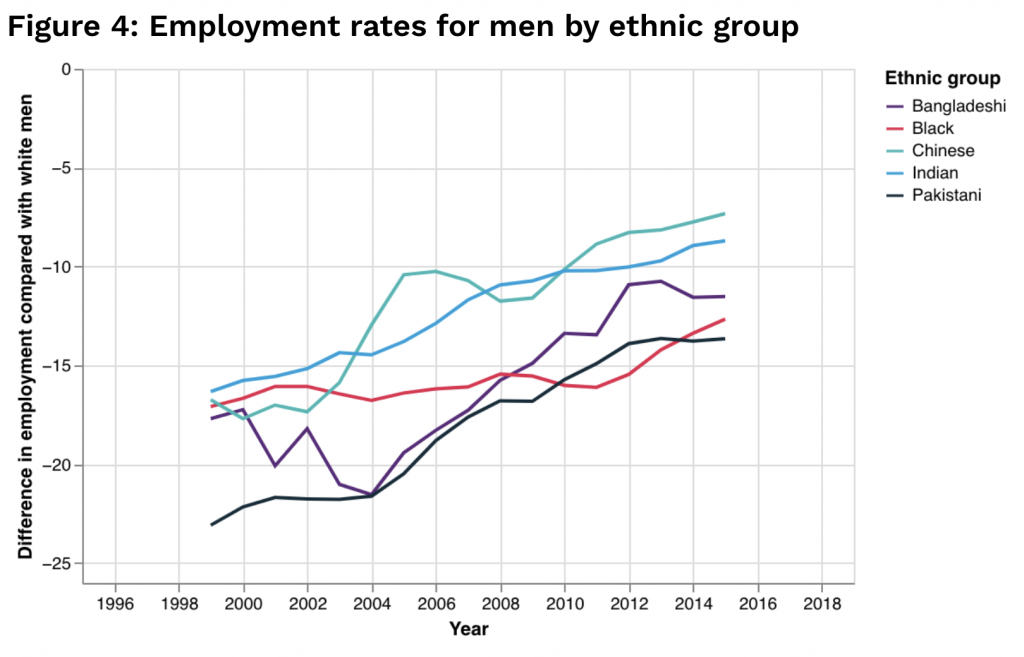

The Sewell Report presents estimates of employment and unemployment rates over time but does not adjust these for characteristics as is done for the pay differentials. But it is important to look at employment rates adjusted for characteristics just as for pay.

These employment rate differentials are all negative, indicating lower employment rates for ethnic minority women, with the gap being lowest for black women and highest for Pakistani women. For the Chinese and, less so, for Indians and Bangladeshis, the differentials are falling but remain large. There is little sign of improvement for black and Pakistani women over the 25-year period.

Again these differentials are all negative, but the ethnic employment penalty has been declining over time for all groups.

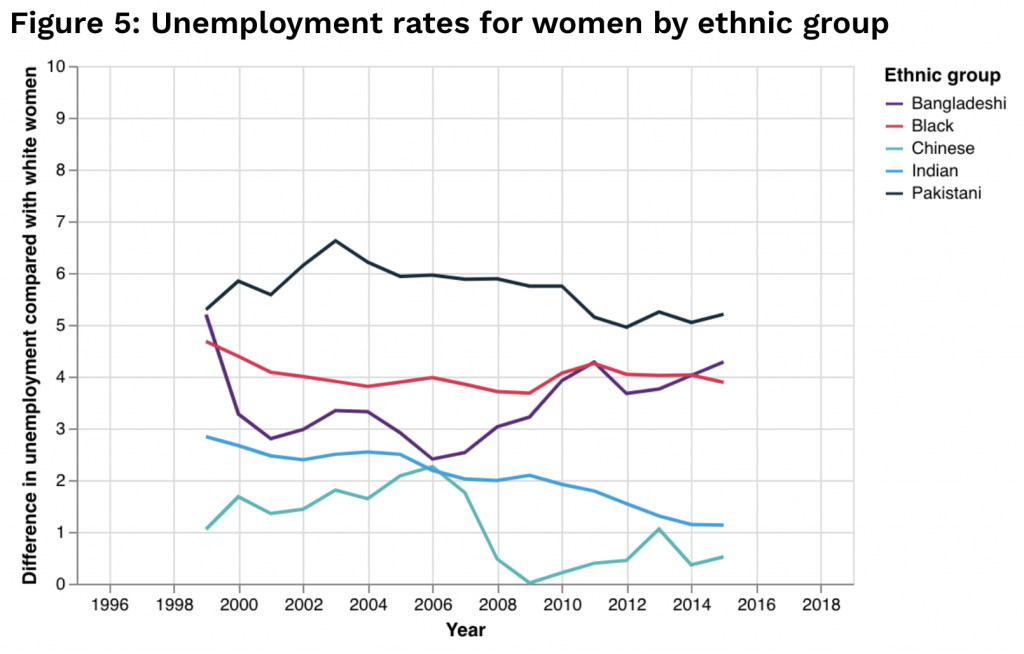

Some of those who are not in paid work do not want employment – they are what are known as the ‘inactive’. They may not be as much of a concern as those who want work but do not have it – the unemployed. Figure 5 shows the unemployment rate differentials between ethnic minority and white women.

These are all positive, indicating that all groups have higher unemployment rates than white women. Only for Indians has the gap clearly been declining over the past 25 years.

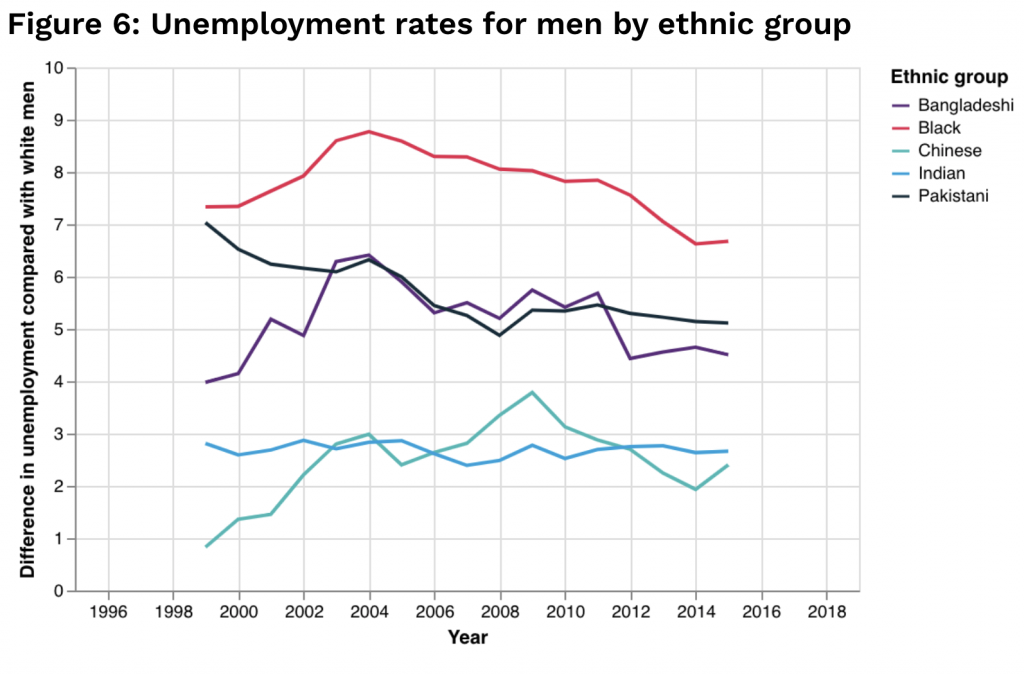

Again, these are all positive, indicating higher unemployment rates for ethnic minorities compared with whites. Only for Pakistanis is there a clear decline in the unemployment penalty over the last 25 years.

What are the causes of labour market differentials?

Although there are some groups for some labour market outcomes where there is clear evidence of reducing ethnic penalties over the past 25 years, the over-riding impression is of stasis. Analyses like those done here can only describe the differences in outcomes: they do not tell us about the causes. They should be the starting point for a more thorough analysis not the endpoint. The differentials can have many different causes but we do have good evidence that discrimination is part of the story.

The Sewell Report describes the results of the field experiments of job applications that control the content of the CV and show convincingly that having a name that suggests being from an ethnic minority lowers the probability of receiving a call-back. This is obviously unacceptable, and the report does say these studies provide conclusive evidence of bias in hiring and that this needs to be investigated further.

Rather oddly, the report then goes on to say that ‘these experiments cannot be relied upon to provide clarity on the extent that it happens in every day life’ when they definitely can because of the nature of the design of the experiment. It is clear that more work is needed to understand the causes of ethnic minority penalties in the labour market and what can be done about them. A good place to start would be the scandal that your name influences your chances of getting a job interview (and probably of getting a job).

____________________

The above was first published on the Economics Observatory website.

Alan Manning is Professor of Economics at the LSE and an Associate at LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance.

Alan Manning is Professor of Economics at the LSE and an Associate at LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance.

Rebecca Rose is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Economics at the LSE.

Rebecca Rose is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Economics at the LSE.