Mark Fransham and Insa Koch examine how intensifying inequality in the UK plays out at a local level. They distinguish differing dynamics of ‘elite-based’ polarisation (in Oxford and Tunbridge Wells) and ‘poverty-based’ polarisation (in Margate and Oldham). They write that, although across these four towns marginalised communities express a sense of local belonging, tensions between social groups remain strong and all towns are marked by a weak or ‘squeezed middle’.

Mark Fransham and Insa Koch examine how intensifying inequality in the UK plays out at a local level. They distinguish differing dynamics of ‘elite-based’ polarisation (in Oxford and Tunbridge Wells) and ‘poverty-based’ polarisation (in Margate and Oldham). They write that, although across these four towns marginalised communities express a sense of local belonging, tensions between social groups remain strong and all towns are marked by a weak or ‘squeezed middle’.

Could the coronavirus pandemic be the catalyst for a new welfare state settlement which addresses contemporary injustices? Can it act as an occasion for re-politicising entrenched inequalities in Britain? The pandemic has undoubtedly increased the public awareness of inequalities in housing, education, employment and health, but the lack of mediating figures or institutions in the local practice of politics ‘on the ground’ continues to be a barrier to collective political organisation.

We studied four English towns in the two years immediately before the coronavirus pandemic. Across the places, and despite having very different social and political features, mutual support networks and the desire for collective change was strong on the grassroots level, particularly amongst those most harshly hit by inequalities. Yet, these community groups had few links with each other or with the elite groups that wield the power to push for action. Moreover, there were differing forms of entrenched social polarisation – at times defined by the presence of a large ‘elite’, at times by that of a large ‘precariat’ – that militated against the process of building the broad-based political coalitions required to push for change.

Margate, Oldham, Oxford and Tunbridge Wells, the four towns in our study, have very different politics, histories, and identities that provide interesting comparisons for analysis. All these places have strong industrial histories that loom large in the popular consciousness of working class residents, but in recent decades Margate and Oldham have become economically depressed areas whereas Oxford and Tunbridge Wells are among the most prosperous parts of the UK, with pockets of deprivation within them.

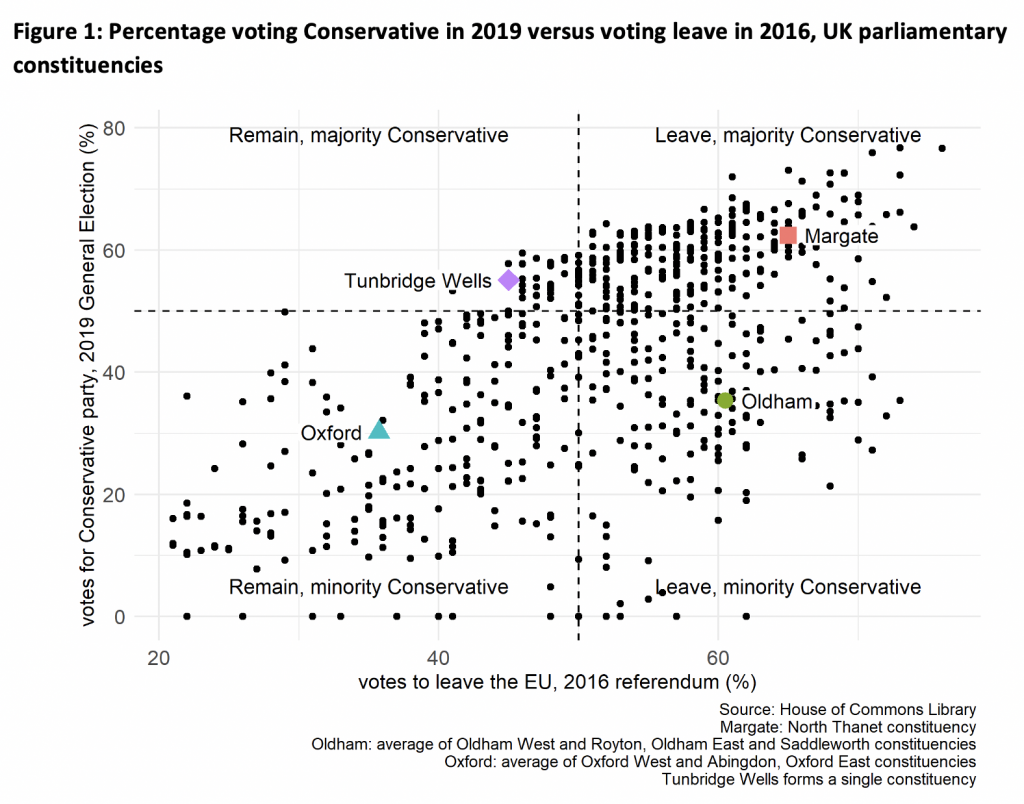

Recent voting patterns have been quite different in the four areas. This is shown in the chart below which compares the votes in the 2016 EU referendum and the Conservative vote share in the 2019 General Election, broken down by parliamentary constituency. Two of our towns, Oldham and Margate, were leave-voting places whereas Oxford and Tunbridge Wells voted to remain in the EU. These places are split again by their vote in the General Election, where the areas of Labour strength include leave-voting Oldham and remain-voting Oxford, and the Conservatives won in both ‘Remain’ Tunbridge Wells and ‘Leave’ Margate.

In the four towns we investigated the extent to which they were polarised in economic, geographic, and relational terms, combining statistical analysis with a bottom-up ethnographic approach. By polarisation we mean that not only are there inequalities within a place but that the ‘middle’, however defined, is relatively small by comparison to the extremes. In economic terms, this could refer to the shrinking of mid-wage jobs relative to the growth in low wage and high wage jobs at either end of the spectrum. Geographically, this can mean the segregation of social groups into different parts of a town. In relational terms, this could mean the segregation of social groups into parallel lives with limited connections or networks between them.

There are two distinct patterns of economic and geographic polarisation in our study areas. In Margate and Oldham, socially deprived populations are concentrated in the town centre, and economic inequality is characterised by high levels of poverty and a higher than average proportion of people in the lowest occupational class. In Oxford and Tunbridge Wells, socially deprived populations are pushed to the periphery of the towns onto outlying housing estates. Economic inequality is characterised by the existence of an elite population with high incomes and high pay occupations. We refer to this as the difference between ‘poverty-driven’ and ‘elite-driven’ polarisation, respectively. In all places there was evidence of occupational class polarisation, but little evidence of a polarised income distribution.

In relational terms, there were some strong common factors as well as differences. In all four towns there was a strong sense of devaluation and stigma experienced by working class populations. In Oldham and Margate, this affected the population of the entire town, leading one person to say that ‘I would not be proud of being from Oldham and I would never like to admit that I was from Oldham’. In Oxford and Tunbridge Wells, places widely considered to be ‘success stories’ to their prosperity, people spoke of how their neighbourhoods in peripheral housing estates were written out of ‘official stories’ of their towns. But these stories of devaluation also went hand in hand with a pride in the industrial, working class histories recollected by older residents – cotton in Oldham, tourism in Margate, car manufacturing in Oxford, and brickworks in Tunbridge Wells. This defiant pride provided the basis of a sense of a belonging which in turn provided the foundation for much grassroots activity, often along informal lines. We found this is all areas, for example food banks, community-run cafes and informal networks of neighbour support.

Divisions and differences in the towns found expression according to whether class polarisation was driven by the presence of a visible elite. In Oxford and Tunbridge Wells, working class residents expressed strong antagonism towards the town’s elites, feeling that priorities expressed in town politics indicated that the place was not for them. In Tunbridge Wells, this was exemplified by a £77 million new theatre intended to ‘bring the West End to Tunbridge Wells’. In Oldham and Margate, places without a strong elite presence, divisions were more likely to be expressed in intra-class terms. The scarcity of services due to austerity policies loomed large in conversation, sometimes viewed through the lens of racism and migration – with recent migrants from Eastern European countries including Roma people often bearing the brunt. These divisions were often recognised and attempts to bridge them made, such as the ‘Interfaith Forum’ in Oldham.

In all four areas, the presence of a large middle income group of residents that spanned the divide between those with the lowest and highest incomes was socially and culturally weak, and unable to shape local relations or bridge differences. In elite-driven Oxford and Tunbridge Wells, there was a strong sense that the middle was ‘squeezed’, with one resident saying ‘we’re becoming more kind of wealthy people and really desperate people’. Although the middle is well represented in local activism in Oxford, local initiatives representing their interests (including around questions of affordability of housing) were almost entirely divorced from the grassroots activities of more disadvantaged populations. In Oldham and Margate, the middle was not so much squeezed as absent, with middle class professionals living outside the towns. A ‘new’ middle was becoming evident in Margate, with arts-led regeneration encouraging the migration of ‘down from London’ creatives drawn to the new cultural and edgy scene. Nonetheless, this new group has created its own ‘hipster’ spaces separate from the existing white working class and migrant Eastern European populations, with little evidence of bridges being built between them.

The COVID-19 pandemic has undoubtedly increased the public awareness of contemporary inequalities and injustices and galvanised localised networks of support in the most disadvantaged communities, as local food banks and community-run initiatives have shown. Nonetheless, more concerted political work ‘on the ground’ is required if this raised awareness is to translate into collective political action for change. Recent research has found that geographic inequality is one of the dimensions of inequality that the British public find most troubling. If the most disadvantaged places are to find their voice in tackling such inequalities, local mediating institutions and actors who can build broad coalitions by bridging the gap between different groups need to be strengthened. Perhaps, in the wake of the pandemic, this voice has more new impetus to be both formed and heard.

____________________

Note: the above draws on the authors’ work published in Sociology.

Mark Fransham is Senior Research Officer at the Department of Social Policy & Intervention at the University of Oxford, and a Visiting Fellow at the International Inequalities Institute at the LSE

Mark Fransham is Senior Research Officer at the Department of Social Policy & Intervention at the University of Oxford, and a Visiting Fellow at the International Inequalities Institute at the LSE

Insa Koch is Associate Professor of Law and Anthropology in the Department of Law at the LSE.

Insa Koch is Associate Professor of Law and Anthropology in the Department of Law at the LSE.

Photo by Brett Jordan on Unsplash.

Excellent read. Thank you for sharing these insights.

As some that grew up in a low-income household and is now a high-rate tax payer, I find myself empathising with the lower-income group whilst finding myself in ‘elite’ spaces. I attribute my social mobility not only to my abilities and luck but also to opportunity provided by the government (good education, affordable university, free school meals, child benefit).

I do think that in order to actually improve inequality and social mobility, the lower income population have to see that austerity and lack of investment in the creation of opportunities are key factors leading to the current circumstances. Immigration is only one aspect and it has been used as a scapegoat in politics. Investment in underserved parts of the UK is an opportunity for growth and prosperity. People in ‘elite’ cities are sick of it and would rather move somewhere where they can actually have a community. Those in ‘impoverished’ areas would also benefit from investment which will also encourage others to move into the area and spread out the concentration of capital in the capital!