Richard Murphy argues that the government needs to start focusing on creating jobs rather than on cutting taxes for the highest income earners. He claims that the 50p tax rate has not been easy to avoid as many have argued, and that replacing it with a new mansion or wealth tax will not not bring in the same amount of revenue. The government would better serve the economy by stimulating it through spending.

Richard Murphy argues that the government needs to start focusing on creating jobs rather than on cutting taxes for the highest income earners. He claims that the 50p tax rate has not been easy to avoid as many have argued, and that replacing it with a new mansion or wealth tax will not not bring in the same amount of revenue. The government would better serve the economy by stimulating it through spending.

The budget is days away. If the press were to be believed then the big issue is whether or not the 50p tax rate survives, or is replaced by some form of mansion or wealth tax. It is quite extraordinary that at the time that 20 per cent of young people in the UK are unemployed, when almost 2.7 million people in all are unemployed and when over 6 million in total are underemployed, that the tax rate of the top 1 per cent of income owners in the UK is the subject of so much attention. The focus of all political parties in the UK should, surely, be jobs, jobs and the creation of yet more jobs, but that’s not the case. The 50p tax rate is the focus of attention instead. So let me get the 50p tax rate out of the way and then talk about what this budget should be about.

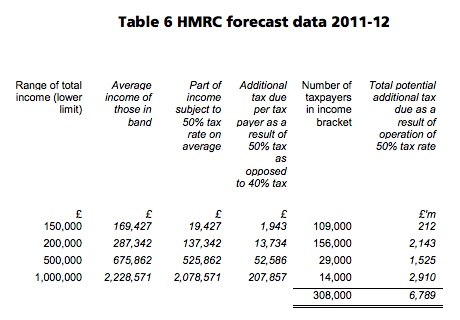

I have researched the 50p tax issue. Using HMRC’s own data I have shown that in the current tax year (2011/12) HMRC expects over 300,000 people to pay tax at this rate. Altogether they will, in HMRC’s estimate, pay £47 billion of income tax. Of that sum I expect £6.7 billion to have been settled at the 50 per cent rate. The detailed workings look like this:

Now of course it can be argued that this is just an estimate and that H M Revenue & Customs has not allowed for behavioural responses to the tax rate change, but that’s precisely why I have used the second year of their estimate and not the first as the basis of my work. It seems very likely that in the first year of their estimate for which this rate is in operation they did indeed allowable for a behavioural response and as a result forecast that the number of taxpayers earning over £150,000 would decrease from 311,000 in 2009/10 to 275,000 in 2010/11.

They also forecast their income would fall slightly from £113.2 billion on 2009/10 to £112 billion in 2010/11. I suspect that’s because they believed there was income brought forward into 2009/10 to avoid the higher rate, as a result of which it seems they expected that a significant number on the margin of this tax rate would succeed in doing. In that case the accusation that these Revenue statistics are mindless extrapolations seems groundless. And I therefore suspect that my conclusions that this tax will be a highly effective revenue raiser; that it will be hard to avoid (especially when HMRC say total tax avoidance is only £5 billion a year) and that few will leave the country to completely get round it, are all true.

Despite that, the arguments to the contrary persist, including the totally contradictory claims that the tax is harmful and yet totally avoidable. Both cannot be true! Logic of this sort has, however, given rise to the alternative claim that a mansion tax or wealth tax might be more useful sources of revenue raising. Neither claim seems at all likely. It seems likely that overall considerably fewer than 1 per cent of all UK residential properties are worth over £2 million. Council tax raises in all £26 billion. The mansion tax adopts a pretty soft approach to collecting revenue from those valuable properties. The chance that it would raise anything like the £5 billion or more I confidently think the 50p tax rate can raise is remote in the extreme in that case. Maybe that’s why some support it.

Wealth tax reforms would be similarly impotent. Capital gains tax and inheritance tax combined right now collect about £6.3 billion between them a year. There’s no prospect, without a radical change of policy that is very unlikely from a conservative chancellor, of any likely wealth tax replacing the lost revenue from a 50p tax rate. And since politically the wealthy can’t be let off tax right now, unless the government wants to suffer the most massive political backlash, the evidence is that this whole debate has been a storm in a teacup that has distracted attention from the real issue for the budgets, and that’s jobs.

Let’s look at the issue of jobs then – and the creation of work. This is essential since it is the shortage of demand that is now the main cause of the UK’s current economic malaise. The stimulus that new jobs could create can only now come from the government. Big business in the UK is sitting on cash variously estimated at between £60bn and £100bn. It’s not spending that cash and it won’t invest it precisely because it firstly believes that its biggest customer – the government – is not going to be spending, and secondly because it believes that consumers aren’t to be spending either. This is the ‘paradox of thrift’ that Keynes so cleverly described at work.

It’s rational for everyone to not spend right now, but if we’re to break the cycle of decline it’s the government that has to undertake the apparently paradoxical act of spending none the less. That’s because since exports are unlikely to be increasing much soon either it is only government spending that can now break the cycle of decline. And although this spending my appear paradoxical by the government it’s in fact the exact opposite: it is the only rational behaviour it can choose since the decline in other economic activity inevitably means (literally through accounting inevitabilities) that the government can never clear its deficit until it does spend to stimulate growth and employment. Until it does automatic spending multipliers, on benefits and services for those out of work, the deficit rises.

That spending by the government could, of course, be funded by tax increases, but that makes no sense at all. That would take money out of consumer spending and simply send yet more people into unemployment as more businesses fail as a consequence. It does therefore have to be funded by borrowing, which is possible at present because interest rates are so low, especially for the government who can borrow at an effective rate of about zero per cent at present. I am told right now that pension funds remain desperate for gilts mixed with index linked products. And that’s where I expect the main source of this money to be.

How to spend it? Well that’s simple. Such funds could finance the government’s ‘Green Deal’; a potentially huge energy saving programme covering 14 million homes, and support at least 65,000 jobs in insulation and construction by 2015. This could be linked to the large-scale local authority programmes such as the one underway in Birmingham.

Research by the Green New Deal group, of which I am member, has shown that an additional investment of £20 billion spent on solar PV for the 3 million best suited roofs could create 140,000 jobs, with households saving up to £250 annually in reduced electricity bills. The long term gain is also energy import substitution, and that protects our currency. These jobs would be generated in the localities where people live and help provide employment and a career path for many of the 1 million unemployed under 25 year olds.

In one imaginative and fiscally responsible measure, both the young and elderly benefit, as pensioners would enjoy a safe refuge for their pensions, through an act of inter-generational solidarity. That’s what this budget needs. But I’m not holding my breath.

Please read our comments policy before posting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics.

Richard Murphy is a UK chartered accountant. Having been senior partner of a practicing firm and director of a number of entrepreneurial companies he shifted towards a research focus for his work when he helped found the Tax Justice Network in 2002. He now directs Tax Research UK and writes, broadcasts and blogs extensively, the latter at http://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog. He has been a visiting or research fellow at a number of UK universities and is the author of ‘The Courageous State’ (2011).