Despite being only 30 miles apart, Liverpool and Manchester have been rivals and institutionally distinct for most of their history. Sebastian Dembski examines the Ocean Gateway investment strategy that is being initiated by Peel Holdings and which aims to bring the two cities together.

Despite being only 30 miles apart, Liverpool and Manchester have been rivals and institutionally distinct for most of their history. Sebastian Dembski examines the Ocean Gateway investment strategy that is being initiated by Peel Holdings and which aims to bring the two cities together.

It’s almost old wisdom that the institutional shape of cities is an ill-defined representation of the actual urban form and the multiplicity of urban networks. The emergence of new urban configurations – marked by enlarged scale, polycentrism and strong cities – often conflicts with the settled institutions of the ‘old’ city, with its hierarchical, centripetal development model. This model is challenged through the autonomous locational decisions of commercial and private actors, and sometimes through planning initiatives that aim to establish new planning spaces adapting to this new spatial reality. Policymakers and strategic planners (whether public or private) pay a lot of emphasis to the marking of change through a whole series of imaginative devices, including language, images, stories and iconic architecture to mobilise all sorts of actors as to establish a new governance space.

The urbanised zone of the Manchester and Liverpool city regions provides an excellent example to study disruption and reshaping of entrenched institutions. The massive Ocean Gateway investment strategy of Peel Holdings, a Northwest-based infrastructure, transport and real estate company, challenged the city regional institutions of the North West, trying to reframe the Manchester and Liverpool corridor under the label of Ocean Gateway. Manchester and Liverpool are only 30 Miles apart, connected by the River Mersey and the Manchester Ship Canal. Although the relationship between Liverpool and Manchester has been characterised as symbiotic, the dominating picture is one of competition and deeply rooted rivalry. Institutionally, the cities have been separate for most of their history.

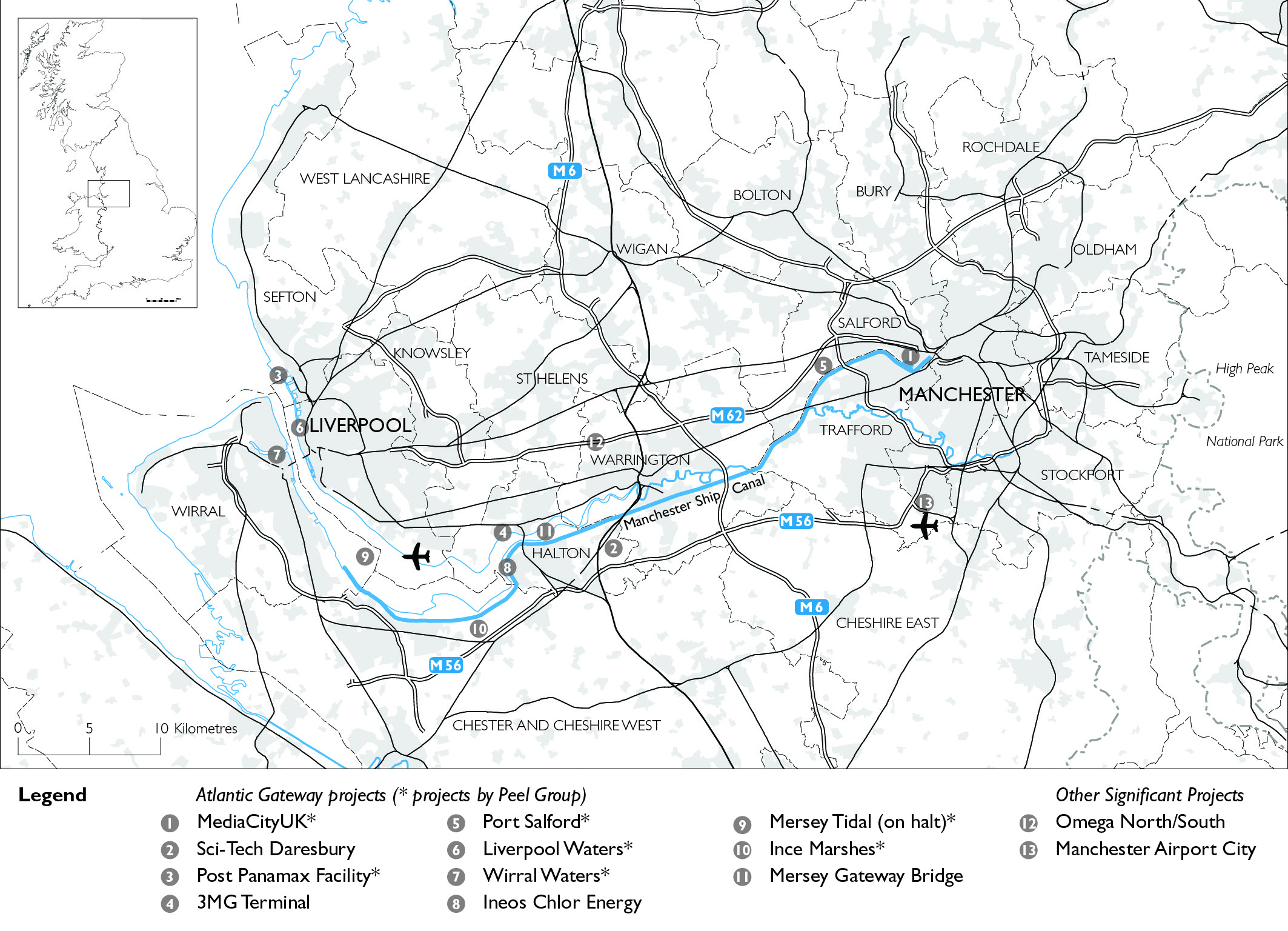

Ocean Gateway, which was launched in September 2008, is a £50 billion investment strategy for the Manchester ship canal corridor for the next 50 years. It is not the first strategy that aims bringing together the Liverpool and Manchester city regions, but the best resourced one. The proposal includes 50 projects that are entirely drawn from Peel’s own portfolio, some of which are being realised independent of the concept. The strategy is organised around three themes. The first strand centres on the notion of ‘SuperPort’, integrating various modalities into a single logistics concept in order to realise a ‘low carbon green corridor’. Another set of projects is concerned with regeneration, including massive flagship developments such as Wirral and Liverpool Waters on either side of the Mersey (‘Dubai on the Mersey’), and MediaCityUK in Salford Quays. The third theme focuses on environmental resources and green infrastructure projects (e.g. Mersey Tidal Power, Ince Marshes Waste Management Facilities and Ocean Gateway Regional Park).

Figure 1: The Atlantic Gateway projects (click on image to enlarge)

By announcing such a massive strategic investment proposal Peel forced the public actors to position themselves. Ocean Gateway was challenging the established institutions of the two ‘isolated’ city regions. One might expect that in an area that is just creeping out of a long economic recession such a massive investment might spur excitement. The Northwest Regional Development Agency (NWDA) had a crucial role in transforming Ocean Gateway into a public sector public sector strategy. In particular Manchester had strong reservations against the concept, as it was potentially disruptive to their successful modus operandi, i.e. the successful collaboration within Greater Manchester. Nevertheless, after a political process and a change of name Atlantic Gateway was launched in March 2010. It sustained the abolition of regional institutions, because Peel pushed the sub-regions to install a private sector-led Atlantic Gateway Partnership Board, which has become operational in 2011 and provide strategic leadership.

Peel’s investment scheme has to a certain extent successfully filled the vacuum of strategic regional planning in the North West by providing a coherent narrative for the Manchester and Liverpool city regions. In the absence of meaningful governance structures at the Atlantic Gateway geography level, the government accepted the property developer’s strategy as a legitimate regional vision. The sub-regions have difficulties getting themselves together to deal with the private sector initiative in a meaningful way. Instead they invest lots of energy in working on city regional institution building, developing their own symbolic language. In particular the success story of Greater Manchester is a heavily guarded counter-narrative to Atlantic Gateway. The challenge for the future is whether the two city regions will manage to work together on an imagination that goes beyond the business interest of a private sector company.

This summarises a longer article in Urban Studies, “Structure and imagination of changing cities: Manchester, Liverpool and the spatial in-between“

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting. Featured image credit: david CC BY 2.0

Sebastian Dembski is Post-Doctoral Research Associate in the Department of Human Geography, Planning and International Development Studies at the University of Amsterdam.

Sebastian Dembski is Post-Doctoral Research Associate in the Department of Human Geography, Planning and International Development Studies at the University of Amsterdam.