Social landlords and the government have long neglected their existing housing stock in favour of new homes, leading to a deterioration of safety standards and a lack of accountability. In the case of Grenfell Tower, these conditions led to at least 72 deaths. A year on from the fire, and with problems in multi-storey blocks being uncovered all over the country, Anne Power outlines ten key lessons to be learnt from Grenfell.

Social landlords and the government have long neglected their existing housing stock in favour of new homes, leading to a deterioration of safety standards and a lack of accountability. In the case of Grenfell Tower, these conditions led to at least 72 deaths. A year on from the fire, and with problems in multi-storey blocks being uncovered all over the country, Anne Power outlines ten key lessons to be learnt from Grenfell.

The Grenfell fire was not like other disasters. It showed up terrible weaknesses in public services, particularly social housing. It underlined the gaping inequalities in our society, our reliance on technical systems we don’t understand, our weak control over conditions, our poor enforcement of standards, and a constant downgrading of low cost renting, both social and private.

The burnt-out remains of Grenfell Tower are sandwiched between Trellick Tower in Westminster, a listed council block with Right-to-Buy flats now selling for over one million pounds, and the three twenty-three storey towers of the Edward Woods estate in Hammersmith, overlooking Westfield Shopping Centre. Edward Woods is council-owned, overclad like Grenfell, but with more expensive, non-combustible insulation spun from rock. Edward Woods has been managed on-site continually since 1981 and tenants there like their high rise flats.

Poor management and maintenance, poor supervision of the upgrading, poor oversight of fire safety, and poor communication between landlord and tenants, and cost-cutting mark out the “fake” Tenant Management Organisation that was responsible on behalf of Kensington Council. In theory it represented all council tenants in the Borough, taking over all council housing responsibilities in the early 1990s. The multiple failures of this organisation will slowly unfold in the Public Inquiry. It was forced to hand back responsibility a month ago to the Council, the actual owner and landlord.

How did a rich, sophisticated borough make so many mistakes? In the 1990s, giving tenants a stronger voice was the way forward and a unique Kensington version of this important idea took shape. Tenant Management Organisations are small area-based community organisations of around 250 council-owned properties. Tenants take over some local housing management functions, such as odd job repairs, caretaking, environmental maintenance, letting, empty property, employing locally-based staff, often tenants themselves, paid out of rent income. Tenant Management Organisations generally perform better than Councils, cost less money, and create higher tenant satisfaction. Grenfell Tower and Lancaster West estate are not remotely comparable to this successful model. Seven months before the fire, tenants warned of the risk of fire, due to poor quality work, poor management and maintenance, weak regulation and enforcement, and cost cutting on all these fronts.

Problems in multi-storey blocks are being uncovered all over the country. Half of the four million socially-owned homes in England are in multi-storey blocks – roughly 30,000 blocks – with half a million leaseholders, depend on social landlords, who retain responsibility for structural and safety issues. Around 10,000 multi-storey blocks are classed as high-rise, above 18 metres or six floors. Grenfell Tower, Edward Woods, and Trellick Tower are almost four times this height. Many key actors, including social landlords, architects, builders, surveyors, fire services, building and service inspectors, installers, housing managers, and residents are all involved. So how do we secure the future of such complex housing?

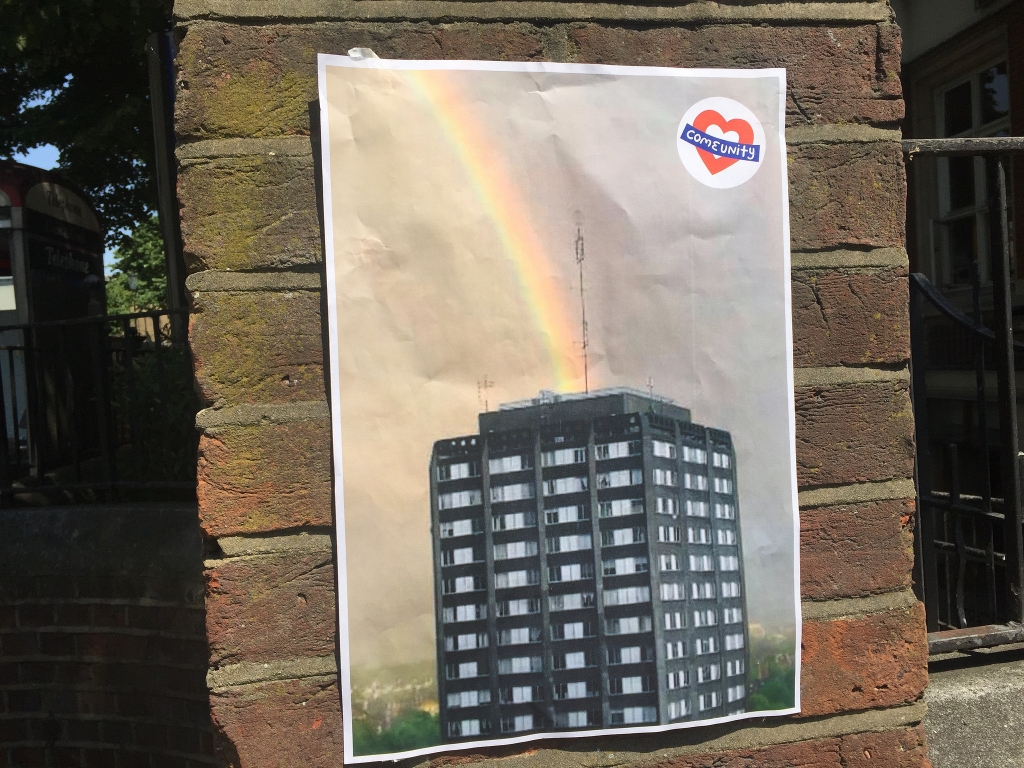

Credit: Matt Brown (CC BY 2.0)

Credit: Matt Brown (CC BY 2.0)

Over the past 11 months, LSE Housing and Communities, in partnership with the National Communities Resource Centre at Trafford Hall, has worked with tenants, landlords and professionals to identify the most important lessons from Grenfell. We found ten.

Lesson 1: There should be a single point of control for any multi-storey block so that everyone knows, whether it is staff, residents or emergency services, where to go and who is responsible whenever an emergency arises.

Lesson 2: A full record of work that has been done must be kept, including the costs, the rationale, the specifications and implementation, with a continuous sequence of recorded information from start to finish, handed over on completion to the responsible owner/manager.

Lesson 3: There should be the equivalent of an MOT test for all multi-storey, high-rise and tower blocks as they have complex and linked internal systems, involving the interaction of many different technical features including plumbing, electrical wiring, heating, lift maintenance, roofs, windows, walls, fire doors, fire inhabitors, and means of escape.

Lesson 4: The containment of fire within each individual flat (commonly known as compartmentation) is absolutely crucial. A breach in the party or external walls of flats, often caused by installing television wiring, gas piping, electric wiring, plumbing or other works, creates a conduit for fire.

Lesson 5: In-depth fire inspections should happen every year in every block, using qualified inspectors, checking walls, doors, equipment, cupboards, shelves, etc. to ensure there are no breaches of fire safety or containment.

Lesson 6: Knowing who lives in all the flats within a block, including leasehold properties, private lettings, and subletting with the right to enter, inspect and enforce where there is a potential hazard affecting the block, is essential to exercising control over conditions and safety. Leasehold agreements should specify the obligation to provide access keys in case of leaks, fire, or breaches of containment.

Lesson 7: On-site management and supervision maintains basic conditions and is essential for security. The landlord can then enforce a basic standard, both in the stairwells and within units. The proximity of neighbours makes enforcement of tenancy conditions vital.

Lesson 8: The maintenance of multi-storey blocks is an engineering challenge where precision and quality control are essential. Judith Hackitt’s Interim Review of Building Regulations recommends higher standards, stronger enforcement, and far greater professionalism in designing, delivering, and running complex multi-storey buildings.

Lesson 9: There should be no shortcutting on cost and quality as short term savings can lead of long-term costs, as Grenfell Tower shows.

Lesson 10: Tenants are entitled to have a voice in the safety, maintenance, and general condition of their blocks. They often know more than staff about who lives in blocks and about earlier works as they have often been around longer than housing staff. They know what changes have been made. They are valuable conduits for vital information, and can thus help their landlords and their community.

Both social landlords and the government have neglected their existing stock in favour of new build housing for too long. Theresa May, the Prime Minister, said this after the Grenfell fire. Diverting resources from new build for sale to existing homes for low cost would reduce homelessness, cut Housing Benefit costs, stabilise vulnerable communities, improve conditions, and crucially reduce the risk of fire or other disasters. Investing in existing social housing would give an important signal to society that it matters; it would encourage tenants to invest in their homes. It is invariably far cheaper to upgrade and manage intensively existing homes than to demolish, for they are an irreplaceable source of cheap, accessible homes.

Anne Power is Professor of Social Policy and Head of LSE Housing and Communities.

Anne Power is Professor of Social Policy and Head of LSE Housing and Communities.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Great lessons, hind sight can be a wonderful thing, lets hope the lessons learned stop it from happening again. Shame it wasn’t prevented prior.

Great article Anne.

Anne,

It’s an absolutely thorough list.

2,3,9 & 10 particularly chime with me.

But you don’t specifically highlight the important aspects of high rise blocks which arise just because they are high.

You can just tumble out of a bungalow window. It takes many minutes to get out from the 13th floor, especially when no one can use the lifts.

Secondly it’s not just the holes and gaps caused by installation of services. High rise buildings have a huge “chimney effect” in case of fire. Even non-flammable cladding is not mortared perfectly solidly to the walls. So hot air rises faster and faster, and hotter and hotter, in the “chimney” between cladding and wall, and causes spontaneous combustion higher up. Even in the absence of actual flames. In the days of coal fires, we used to hold a newspaper across front of the fireplace to get it “drawing” and the coal ignited. That’s what happened at Grenfell and at previous cladding fires in Europe and Australia.

The relaxation of Building Regulations, when they should have been tightened for high rise buildings, was opposed by almost all of us who worked in housing or building control. I wanted external cladding banned for all high rise buildings. But successive governments and civil servants (and councils) ignored such advice, and it became the cheap and easy way to change an estate.

A better way is to start with your No 10 and Tenant Management Organisations.

( P.S. You know this stuff, the detail above is for your readers who may not).

Having attended one of these sessions it’s really great to this published. Some of these lessons are so fundamental and can easily be resolved.

I really hope the sector works collaboratively to ensure consistency.

I insure property and liability risks pertaining to high rise building for RSLs and I would point to the Scottish 2005 building regulation change that banned use of the ACM materials in high rise blocks.

I would also say that throughout my career these insulation products have morphed from industry to residential use.

They first appeared in commercial premises where they offered good insulation to the shed like warehouse out of town sites. They also contributed to the first death of a female firefighter, Fleur Lombard, in peacetime. Their use was then shunned in commercial premises as insurers applied terms.

No doubt post the failure in commercial premises meant a new market was sought, under the guise of environmental energy saving, this being residential and with obviously tragic outcomes.

So whilst the above actions are useful Action 1 on day one should have been to follow Scotland and protect the citizens of these blocks. We are not even there yet.