The fact that Theresa May and Jeremy Corbyn are now less popular than Nigel Farage is in large part the result of their attempt to lead the heterogeneous movements they inherited, writes Ben Margulies.

The fact that Theresa May and Jeremy Corbyn are now less popular than Nigel Farage is in large part the result of their attempt to lead the heterogeneous movements they inherited, writes Ben Margulies.

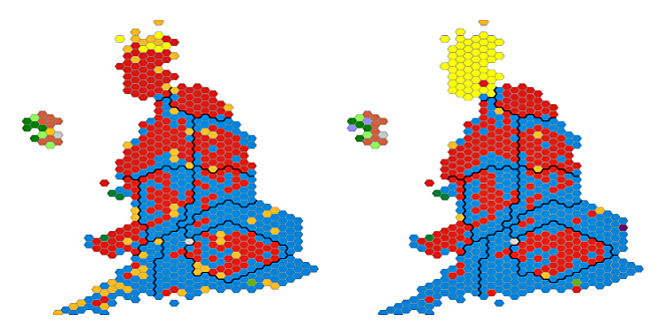

The Conservative and Labour parties are seeing an alarming fall in support. Thanks to the prolonged denouement of the Brexit crisis, both parties have bled up to half of their 2017 supporter base. A great deal has been written about why they have come to this pass, and for the most part the cause seems to be Brexit: the two parties are being torn apart because their voters cannot agree on the cultural and economic questions posed by globalisation. Others would say that the Conservatives and Labour are falling prey to the superior competitiveness of ‘populists’. In an age when economic crisis, scandal, and the disintegration of mass parties have left political elites estranged from their electorates, no politician or party can easily prosper against the powerful appeal to anger and frustration made my populist leaders.

But this divide between ‘elite’ and ‘populist’, or ‘establishment’ and ‘outsider’ is not clean cut. The Conservative and Labour leaders have adopted extensive elements of populist framing, discourse and styles. Theresa May has raged against Parliament and the opposition; Jeremy Corbyn against the press, civil service, and the ‘elites’. What features mark out this populism? Why is it different? And why hasn’t it worked for its practitioners?

Firstly, populism can mean a ‘thin-centred ideology’ or political style, both of which will usually cast political conflict as a battle between a ‘good’ people and a ‘bad’ elite. The goal of politics is to make real the will of the people, which is portrayed as united and singular. Courts, bureaucracies or the mass media are seen as dubious at best, generally because elites staff them and they contain the popular will. Populists tend to discount the idea of a loyal opposition. Finally, many – but not all – theorists of populism focus on the need for a leader to represent and embody the people, usually through charismatic authority.

Jeremy Corbyn has long been associated with a sort of left populism, one which sees the people and elite as differentiated on economic grounds. Watts and Bale describe how Corbyn used populist framing in intra-party competition within the Labour Party. Although Dean and Maiguashca challenge this depiction of Corbyn as a populist, the dynamics of his relationship with the Labour membership, Parliamentary Labour Party, and the mass media suggest that Corbynism involves at least some populist features, namely appeals to ‘the people’, anti-elitism, a reliance on a direct electoral mandate for a superior sort of legitimacy, and a strong identification of the underlying political project with the person of the leader.

Theresa May, on the other hand, sometimes delivers a sort of right-wing, authoritarian populism. May claimed a mandate to deliver Brexit, and to this end she has often demonstrated an impatience with those institutions that might block this expression of the popular will. May’s government initially resisted any suggestion that Parliament’s consent was necessary to invoke Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty; in 2017, she called a snap election, complaining that Labour, the Liberal Democrats and the SNP would vote against Brexit:

The country is coming together but Westminster is not. In recent weeks Labour have threatened to vote against the final agreement we reach with the European Union, the Liberal Democrats have said they want to grind the business of government to a standstill, the SNP say they will vote against the legislation that formally repeals Britain’s membership of the European Union and unelected members of the House of Lords have vowed to fight us every step of the way. … they underestimate our determination to get the job done and I am not prepared to let them endanger the security of millions of working people across the country because what they are doing jeopardises the work we must do to prepare for Brexit at home and it weakens the Government’s negotiating position in Europe. If we do not hold a General Election now their political gameplaying will continue and the negotiations with the European Union will reach their most difficult stage in the run-up to the next scheduled election.

In a single passage, May identified her cause with a morally righteous people, declared that people unified, condemned elites, and declared opposition illegitimate. Later, she would repeat her anti-parliamentary rhetoric during the battles over her ill-fated withdrawal deal in the spring of 2019.

So if May and Corbyn are both adept at using populist ideas and framing, why are they no longer enjoying the success that other populists – such as Nigel Farage, winner of the last two European Parliament elections – have enjoyed? To begin with, as leaders of the two dominant parties, Corbyn and May have different benchmarks for success – typically, a parliamentary majority on at least 35% of the popular vote. Very few populist parties elsewhere in Western Europe can reach those levels of support.

A deeper reason for May’s and Corbyn’s struggles has to do with the nature of populist leadership. Populists do not just inherit peoples. Rather, they tend to create them, using their rhetoric and persona in order to construct a certain idea of ‘the people’, and to gather together the like-minded under their banner. Donald Trump has done this to a great degree in the United States, convoking a Trumpian base which is distinct from, if not too dissimilar from, the Republican Party’s base. Other populists accomplish this by founding their own parties.

Corbyn and May, on the other hand, became the figureheads of populist sentiments and constructs after the fact. Corbyn did not call forth his base in the Labour membership; left-wing and dissatisfied voters identified him as a maverick and rallied accordingly. May did not create the right populist project that she tried to head; rather, Brexit did, and May simply became leader of the most convenient institutional expression of that social formation. Some have stressed that populist movements can start without a leader, but what the British case seems to be telling us is that adopting a leader a posteriori risks picking one who cannot read ‘the people’, or change tactics when the people’s identity or concerns alter.

The end result is that neither May nor Corbyn possesses the performative, communicative, and analytical skills necessary to be classic populist leaders. They do not control the definition and image of their peoples. They cannot necessarily incarnate them in the way a leader is expected to in many forms of populism – they cannot be the mirror image of their people. Nor have they imposed that image of ‘the people’ on the overall voter coalitions of their establishment parties, which predate their arrival.

And they seem unable to change their political messaging to fit new contexts. Corbyn is unable to provide a Brexit project that unites ‘his people’, because he did not create them. Rafael Behr stated that Corbyn was the chief liability of the Corbynist project – significantly, he added that Corbyn is unable to bridge the gap between his public image and his policies and tactics. May similarly took over a mandate she had not expected and tried to appeal to millions of UKIP voters through the performance of a right-wing, authoritarian populism built around the kernel of a hard Brexit. Between a lack of natural charisma and the strategic impossibility of enacting a hard Brexit without the risk of serious economic damage, her attempt to instantiate a sort of English nationalist subject failed.

Corbyn and May were never classic populists, and their leaderships never fully conformed to most definitions of populist tactics, style or political outlook. Nevertheless, both incorporated aspects of the populist style into their political practice. Still, they did not create their own populist movements – rather, they relied on populist tactics to deal with new political entities they could not adequately understand, embody or manage. The result has been increasing political isolation and failure, and perhaps a lesson for mainstream politicians wishing to join the populist bandwagon.

_______________

Ben Margulies is Lecturer at the University of Brighton.

Ben Margulies is Lecturer at the University of Brighton.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Pixabay (Public Domain).

Refreshing to read a read a clear analytical review, for a change.