The UK faces a productivity crisis and tackling this will be crucial to regaining sustainable increases in living standards. In response, the Autumn Statement announced a large number of measures to try and boost business investment. Anna Valero and John Van Reenen look at these reforms and assess whether they will be up to the challenges that lie ahead.

Despite the Chancellor’s upbeat tone as he introduced the Autumn Statement, the UK economy faces a number of serious challenges. Debt is set to reach over 90 per cent of national income, the tax burden is at a 70-year high and public services are under significant strain. Inflation – while falling – is still far above the Bank of England’s target of 2 per cent with underlying signs of persistence which have led the Bank of England to signal that we are in a “higher for longer” world.

There was no growth in the third quarter of 2023, and no growth in 2024 was forecast by the Bank of England. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) is more optimistic with 0.7 per cent forecast for next year, but this is also well below trend. And overall, the OBR is more pessimistic about the medium-term outlook that in its previous forecasts, even with the package announced yesterday.

Inflation erodes the real value of public spending, implying swingeing cuts to public services and public investment for whoever forms the next government.

The much lauded “headroom” against the Government’s fiscal rules that has opened up is largely illusory. It is due to wage inflation pushing up tax revenues as more workers get captured in higher tax bands due to the Chancellor’s decision to freeze thresholds in cash terms. Moreover, inflation erodes the real value of public spending (which is set in nominal terms), and this implies swingeing cuts to public services and public investment for whoever forms the next government.

Yesterday, the OBR set out how following the measures announced in the Autumn Statement, headroom of around £13 billion remains, which is well below the average headroom of previous Chancellors. So British public finances remain in a tight position that will worsen under future pressures from an ageing population and the urgent need for the transition to net zero.

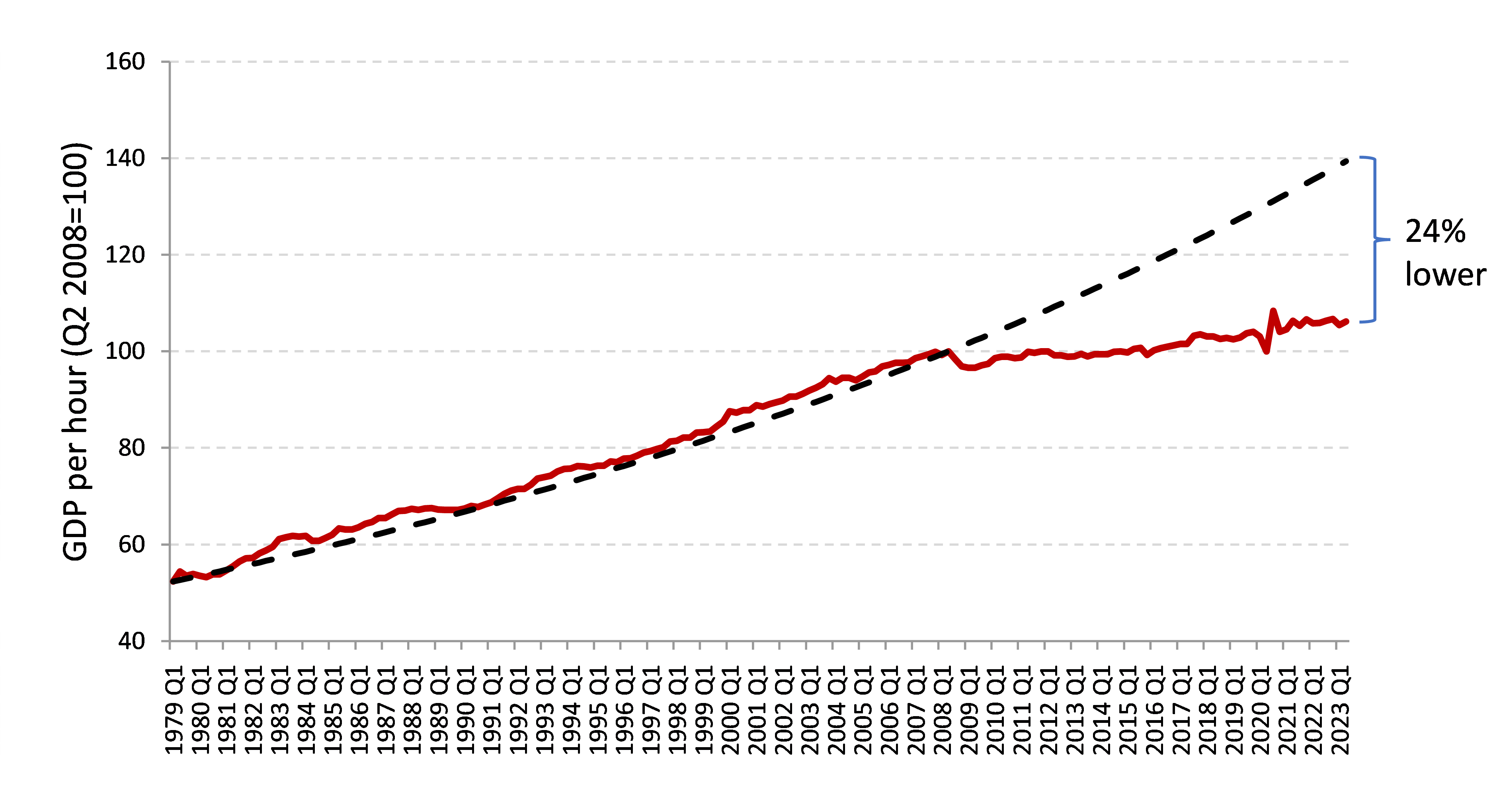

Underlying this challenging outlook is the longstanding problem of weak UK productivity performance. Labour productivity (GDP per hour worked) is 24 per cent lower than it would have been had it grown at its pre-financial crisis rate (see Figure 1), and this has been the main driver of real wage stagnation over the last 15 years. The OBR reckons real household disposable income will be 3.5 per cent lower in 2024-25 than pre-pandemic – the largest reduction in living standards since records began in the 1950s.

Figure 1: UK Productivity is about a quarter lower than it would have been if it followed a pre-crisis trajectory

The business investment problem

Compared to its international peers, business investment has been low in the UK as a share of national income for many years, with businesses investing around 10 per cent compared to over 12 per cent in the US, France and Germany on average. In fact, in the years since 2008 amongst a set of advanced economies, only Greece had a lower investment rate than Britain. Combined with low public sector investment, the result has been a fall in capital per worker. But the UK’s problems extend beyond capital investment, and there is room for improvement when it comes to investing in innovation and skills too.

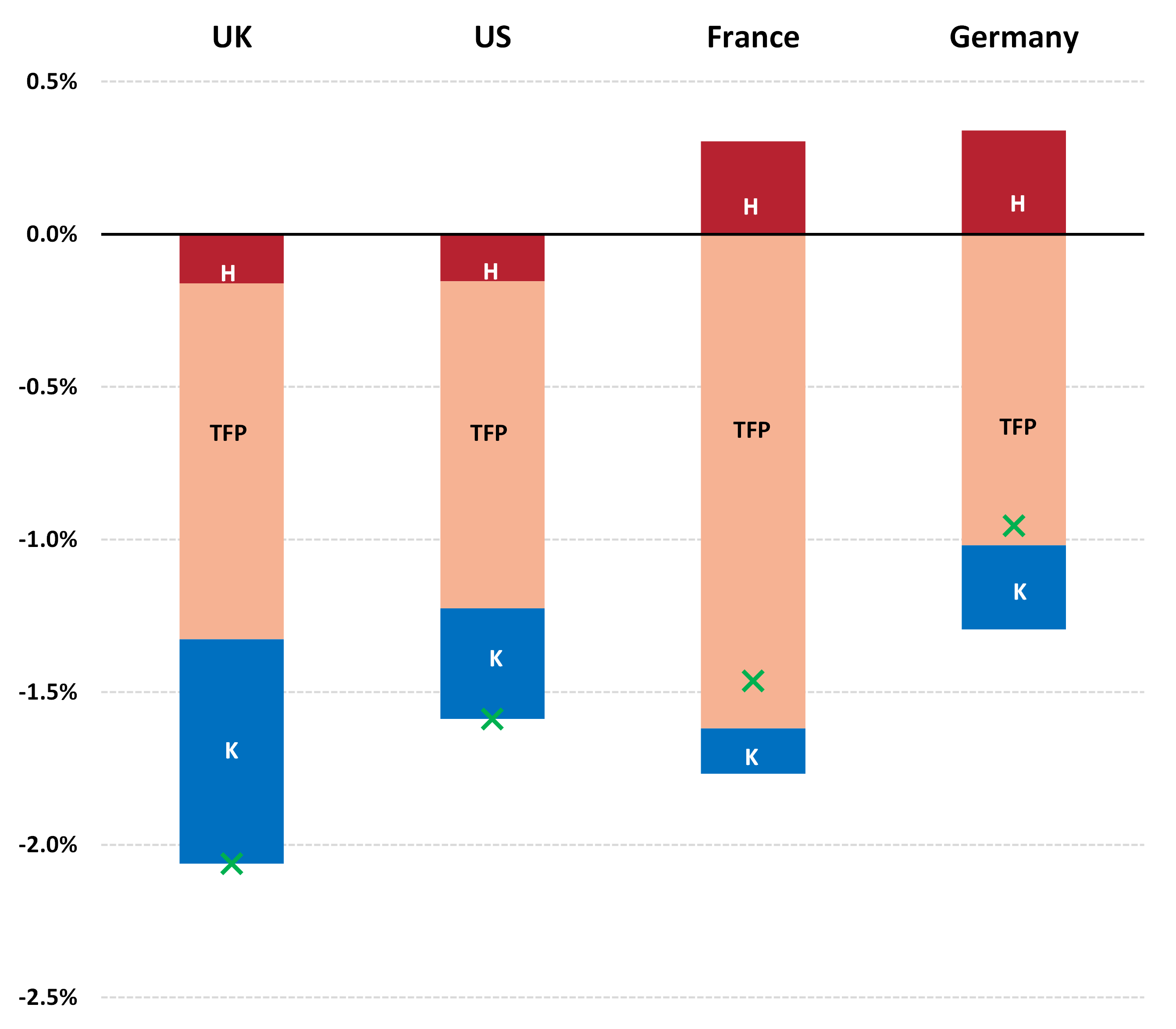

Figure 2 shows that the slowdown in capital accumulation (“K”) has been particularly stark in the UK compared to other countries, and it has also not benefitted from a positive contribution from skills (“H” for human capital) as seen in France and Germany. This failure to invest helps explain why Britain has suffered a more severe productivity slowdown than other countries.

Figure 2: A comparison of productivity growth before and after the financial crisis shows that the slowdown in capital accumulation has been a key issue for the UK

Source: Van Reenen and Yang (forthcoming, 2023) using EUKLEMS & INTANProd 2023 release; OECD and other sources.

But it’s not all doom and gloom. The Chancellor rightly pointed to some areas where the UK excels. There are enduring strengths in a number of large, growing areas such as finance, business services, the creative sectors and areas of advanced manufacturing including the life sciences. We are specialised in the innovation of key clean technologies, as well digital technologies such as AI, robotics, and biotechnology. The UK comes fourth in the World Intellectual Property Organisation’s Global Innovation Index – with key strengths relating to the quality of its innovation outputs, particularly from its world class universities.

There is no lack of investment opportunities but making the most of these – and translating them into productivity growth across the country – means getting serious about addressing the barriers that prevent businesses investing for long-term value creation.

Reforms to get businesses investing – a promising start

A series of reforms across tax, pensions, corporate governance, planning and smaller business support, implemented together, and in the presence of public investment and skills reforms, would boost business investment. It was encouraging to see progress on a number of these fronts in the Autumn Statement.

A headline policy announcement was making permanent the (previously temporary) full expensing of business plant and machinery for tax purposes, at a cost of around £11 billion per year by 2028-29. This will have the effect of increasing the capital stock as opposed to merely bringing investment forwards as was expected to be the case with the temporary measure in place until 2025-26. The OBR judges that the impact of permanent full expensing on potential output will build up from 0.1 per cent in 2028-29 to slightly below 0.2 per cent in the long run. This is a first step towards a more radical approach to tackle the multiple distortions in the tax system. Proposals to simplify the R&D tax credit scheme as well as increase generosity for R&D intensive firms are also welcome.

Building on his Mansion House speech earlier this year, the Chancellor committed to further reforms around the consolidation of pensions and complementary policies to help channel institutional investment towards high growth firms in the UK (including a new Growth Fund in the British Business Bank). There is scope to go much further here through a co-design and co-creation of investment vehicles to catalyse private investment towards key policy objectives.

The UK is in urgent need of a more purposeful, targeted and lasting approach to industrial policy, with a focus on growing sectors and technologies where it has current or potential strengths – including clean technologies. The new £4.5 billion package for advanced manufacturing (including clean technologies) is a welcome development, though the new funding applies after 2025.

Other support for net zero was announced ahead of time, in particular higher prices in the Contract for Difference scheme, and planning policies to speed up grid connections and energy infrastructure. A new investment allowance in the Electricity Generator Levy is also positive news for renewables. But there was little new on energy efficiency, despite reports that a rebate to stamp duty on improved properties might be on the cards. More generally, the permanent expensing of capital investment is also likely to benefit net zero investments which are particularly capital-intensive.

Reforms to the planning system are also crucial for getting businesses structures, infrastructure and homes built in the places that need them. It was good that the Chancellor set out measures to accelerate planning decisions by local authorities. But more ambitious reforms are needed to ensure binding plans are in place, set at the right geographic level, and provide incentives to get developments approved. And while the Investment Zone scheme is being extended with a continued focus on building clusters around the UK’s universities, we remain concerned about risks of simply displacing economic activity from one part of the country to another, rather than raising overall national growth.

Long term economics versus short-term politics

This was a pre-election Autumn Statement, and there were short-term political motivations to show that the government was committed to cutting taxes. The reality is, however, that the overall tax burden is rising and is set to reach a post-war high of 37.7 per cent of GDP in 2028-29. The announced cuts to employee and self-employed National Insurance Contributions (worth £10 billion by 2028-29), as well as the full expensing of business investment have simply reduced the extent of this rise.

The Chancellor is relying on cuts to public spending and investment (largely pencilled in for post-election) to fund his pre-election tax cuts and maintain headroom. The decision to cut spending and finance tax cuts is a policy choice.

A coordinated approach to growth is needed in order to make real progress and this includes raising public sector investment and reducing its volatility.

While many of the reforms on business investment are long-term by nature – it is clear that ensuring that high quality public services are in place, and investing in hospital and school buildings, the science budget as well as other public infrastructure including for net zero will be crucial for the long-term health of the economy, as well as crowding in business investment further. From a growth perspective, the fact that the share of national income going to public sector capital formation is set to fall from 3.6 per cent this year to 3.1 per cent in 2028-29 is worrying. A coordinated approach to growth is needed in order to make real progress and this includes raising public sector investment and reducing its volatility.

Policy stability also matters for investment, and business policies have been subject to a particularly high level of churn in recent years which, alongside political instability and macro shocks, has generated huge uncertainty for businesses. The establishment of a new independent growth and productivity institution would facilitate long-term decision-making in light of short-term political pressures. On November 27th we will publish further analysis of the UK productivity position, more detailed proposals on growth and what institutions could deliver them as part of National Productivity Week.

And more broadly, the UK is in urgent need of a new economic strategy to improve growth in a sustainable and inclusive way. And a major Economy 2030 Inquiry conference on 4 December will set this out, describing a path to a fairer and more prosperous future.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: HM Treasury via Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Deed | Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic | Creative Commons